As the economist Herman Daly pithily said, the economy is a wholly owned subsidiary of the environment – not the reverse. Nature makes our lives possible through what scientists call ecosystem services. Think healthy food, clean water, feed for livestock, building materials, medicine, flood and storm control, recreation, and attractions for tourists.

Despite this, Australian businesses and financial institutions have so far failed to track how their activities both rely on and affect nature. This means our investments and superannuation could be exposed to hidden financial risks because of nature loss – and may also contribute to the destruction of nature.

That’s set to change. The private sector is waking up to nature’s value (and the risks of losing it). The world’s biodiversity rescue plan agreed to last year could help motivate governments and businesses to clean up their investments by directing more money to protect nature and less towards bankrolling extinction.

There’s one crucial plank we’re missing though – mandatory reporting of how businesses both depend on and impact nature.

Nature and financial health are inextricably linked

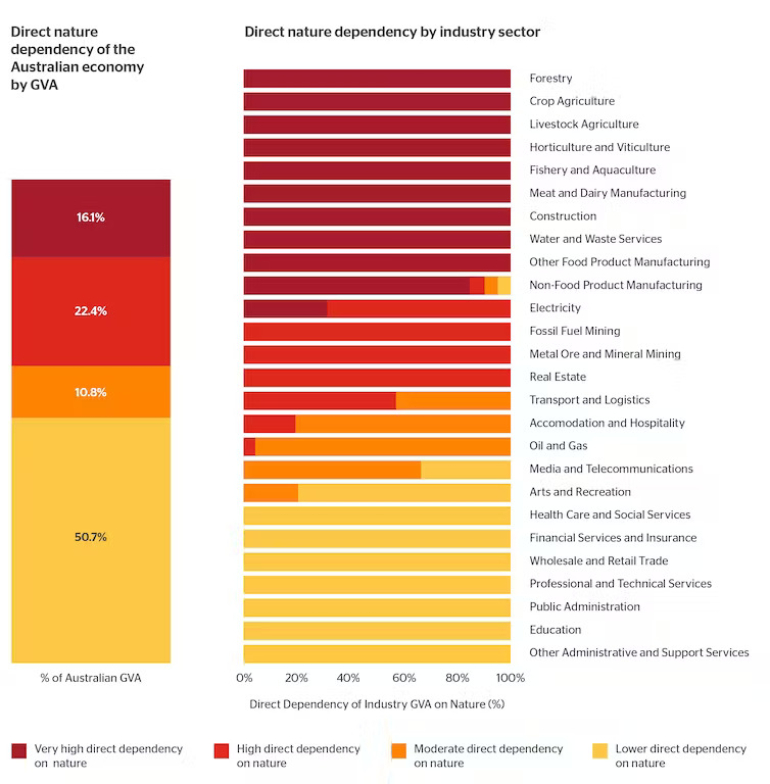

Fully half of the world’s total economic activity – around A$61 trillion – is moderately or highly dependent on nature and its services.

In Australia, that figure is very similar: around half of our GDP – $896 billion – has a moderate to very high direct dependence on ecosystem services provided by nature.

What happens when we breach nature’s limits? Ecosystem services seize up or collapse, eventually disrupting these sectors. The tireless pollination work of honeybees, for instance, is valued at $14 billion a year. Or take Australia’s wheatbelt, where poor soil health is now costing farmers almost $2 billion a year in lost income.

Ecosystem services are not hypothetical. They have real value – and we will absolutely notice if they are gone.

What does this have to do with my super?

Australia’s super sector is responsible for the retirement savings of around 12 million Australians. Super funds are directly exposed to financial risk from nature loss through their investment portfolios.

Just as farmers can’t grow crops without healthy soils or pollinators, developers can’t build apartments without timber or environmental permits. In turn, that has implications for their value as investments.

And because so many sectors are exposed, classic investment strategies such as diversification may no longer protect your super from losses.

So what are our super funds and banks doing about it?

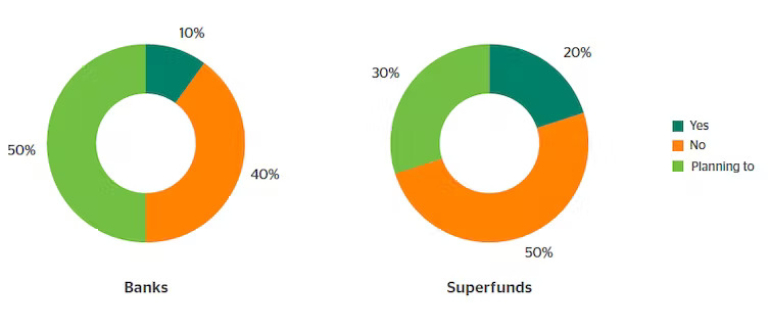

To find out, we surveyed ten super funds and ten retail banks about their responses to nature-related risks. The survey – commissioned by the Australian Conservation Foundation – is the first time this has been done in Australia.

The findings? Not ideal. Every participating super fund and bank agreed the loss of nature now presented a serious risk to investment returns. They all agreed it was part of their responsibility to members and customers to measure and manage these risks. But only 20% of super funds and 10% of banks had attempted to assess how exposed they were.

Again, this is not abstract. Super funds often have large holdings in the big four banks. Together, these banks have $170 billion in exposure to agriculture, mining, fisheries, and forestry – sectors directly reliant on a functioning natural world.

So why isn’t it a higher priority? One issue may be that many financial institutions are currently focused on climate change, given how rapidly impacts are mounting. But climate change and the breakdown of natural systems are twin crises. Nature offers far and away the largest method of taking carbon back out of the atmosphere, for instance. But that only works if salt marshes and wetlands and forests are intact.

Net zero targets for our banks and super funds are not fully credible unless there is a commitment to end the financing of deforestation. Only one organisation, Australian Ethical, had made such a commitment.

You would think Australia’s super funds and banks would be interested to find out how exposed their investments were to this growing risk. Tools to do this such as IBAT and ENCORE are readily available.

But to date, our survey findings don’t indicate banks and funds will do this voluntarily.

Banks and super funds may soon have to report these risks

The biodiversity rescue plan agreed to last year – known as the Kunming-Montreal agreement – is intended to set expectations for responsible finance and business globally, as the Paris Agreement did for climate change.

That means Australia will be expected to introduce disclosure requirements. If this comes to pass, banks, super funds, and the businesses they invest our savings in will have to measure and publicly report their impact on nature – as well as how much they rely on nature to make a profit.

First, though, the Australian government must introduce mandatory nature risk reporting. It’s already moving ahead with plans to make climate risk disclosures mandatory.

Treasurer Jim Chalmers has indicated nature is also on his radar.

The question then will be whether making this information public will actually do what we hope it will and use money to help natural systems rather than extract from them.

What happens next?

Since taking office, the Labor government has pledged to take action on the perilous decline of the natural world with plans such as bringing the value of nature into our national accounts.

While positive, the real action won’t happen until nature risk reporting is mandatory, environment laws with teeth are introduced, and until both governments and private industry direct serious money into helping nature, not harming it. Risky nature credit markets aren’t going to cut the mustard.

You don’t have to sit back and wait. Why not ask your super fund and bank what nature-related risks they are exposing your money to? ![]()

Madeline Combe, Doctoral student, University of Technology Sydney; Megan C Evans, Senior Lecturer and ARC DECRA Fellow, UNSW Sydney, and Nathaniel Pelle, Honorary Associate, Sydney Environment Institute, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.