This US lawyer used ChatGPT to research a legal brief with embarrassing results. We could all learn from his error

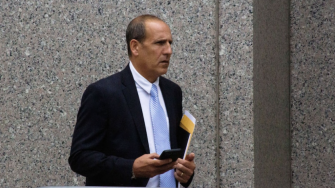

A New York-based lawyer has been fined after he misused the artificial intelligence chatbot, ChatGPT, relying on it for research for a personal injury case.