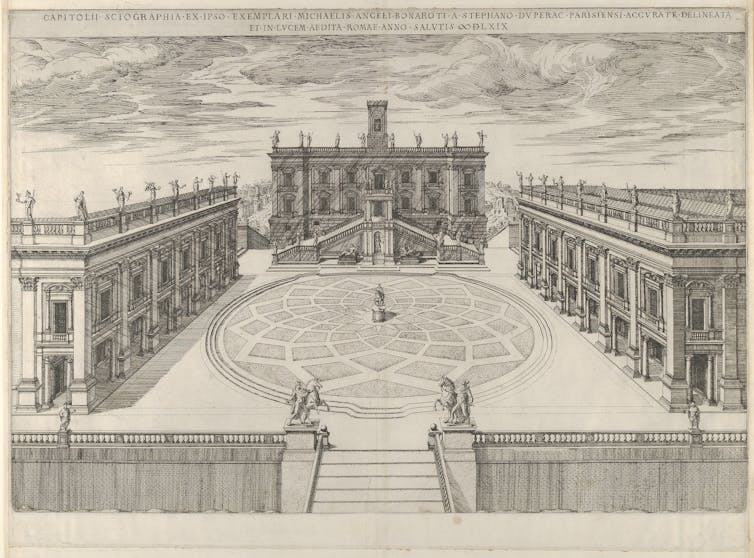

Ancient Rome inspired Washington but its legacy of being open to all has fallen into oblivion

Ancient Rome and its empire had the concept of asylum at its heart. Its legacy provided inspiration for centres of power around the world, but today outsiders are no longer welcome.