In today’s fragile and fractured world, the work of design artist Dr Guy Keulemans feels somehow comforting. It is a reminder that beauty can come from broken things, and that the pieces can be put back together.

His work explores concepts of transformative repair and reuse, and the environmental impacts of production and consumption. Each piece is informed by a sense of its history (material and cultural) as well as his use of artisanal techniques.

“A big part of the underlying theoretical framework that I draw from is critical design,” the lecturer from UNSW Art & Design says. “It's useful because it creates an imperative for a designer to be critical, to not accept the status quo and to actively seek to challenge the damaging institutions and impacts of industry.”

Repair and reuse

Repair and reuse offers a solution of sorts – “if we can keep products in function for longer, then we lessen the impact on the planet,” he says. His work calls for a greater focus on circular economy or circular design where the typical cycle of make, use, dispose is replaced with one of make, use and reuse.

“Cradle to cradle is another term that's used for that, which is really this idea that we shouldn't be extracting resources and using them and then throwing them away into waste, which often ends up in landfill or fortunately, you know, even into the ocean,” he says.

“Circular economy, and circular design, is about creating those loops. Repair and some forms of reuse have much smaller loops than recycling does, which is the main method, or at least the area that's been focused on the most in circular economy.

“Recycling is great … But my interest is not in recycling, because recycling is actually quite a big loop and it breaks down the material sometimes – it has a kind of destructive or semi-destructive aspect – and you also lose a lot of the material culture and the historical values of the material. And I find those [elements] very interesting.

“When you repair an object or reuse it in a certain way and you kind of manage to maintain and conserve a part of its history but in a new product, or perhaps with a new function, it can be a very exciting – kind of a mix of the old world and the new world.”

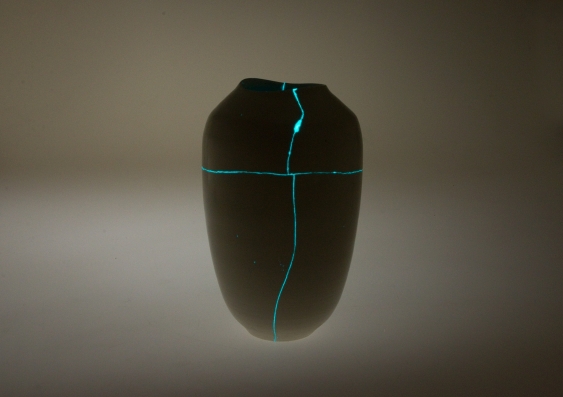

Archaeologic 3 (2015), Guy Keulemans. Ceramic repair with photoluminescent pigment. Bisque made to specification by Kiyotaka Hashimoto. Photo: Sharyn Cairns.

Archaeologic vase series (2015)

The traditional method of mending broken vases involves using urushi, a tree-sap glue, a technique the Japanese have used for thousands of years. “There is historical evidence going back to the Jōmon period of ancient Japan, which is pre-history, of repaired arrowheads and ceramics,” Dr Keulemans says.

“It's also a material that takes years, if not decades, to master. So I decided I'm not going to bother with that. But I'll try something different.

“Instead of just using regular glue … I was thinking, what can I do that actually progresses this kind of genre of repair. And I think photoluminescence is visual, you know, it makes something look brighter in the dark than it does when it's lit.

“And I just really wanted to explore that, that kind of visual character.”

Archaeologic 3 (2015), Guy Keulemans. Ceramic repair with photoluminescent pigment. Bisque made to specification by Kiyotaka Hashimoto. Photo: artist.

Adapting a traditional craft through the use a technological progression is something that really interests the design artist. “Because photoluminescent pigments are relatively recent. They're developed in the early 20th century. They have an interesting and sometimes problematic history.

“For example, there was a factory in the US where they were creating those early, very early glow-in-the-dark watches. And the girls, the – mainly women – that worked in these factories would paint them on with their paintbrush, and they actually got into a habit of like licking the paintbrushes in order to get a very fine tip so they could paint these photoluminescent dials on the watches.

“It turns out that that particular kind of photoluminescent pigment was cancerous – carcinogenic, I should say – so, you know, hundreds of these women died. So, it's an example of one of these industrial tragedies that happen and that we need to be always vigilant about.

“That, again, comes back to being a critical designer – a designer who investigates the paradigms of industry and is always eager to challenge and expose the problems.”

Archaeologic Vase (Series 5, Repair Test) (2019), Guy Keulemans with Kiyotaka Hashimoto. Vase at left, detail at right. Broken stoneware, paint, sterling silver staples. Wheel thrown and fired to bisque by Kiyotaka Hashimoto. Glazed, smashed and staple repaired by Guy Keulemans. Photo: Kristoffer Paulsen.

Dr Keulemans’ father-in-law, Kiyotaka Hashimoto, a traditionally trained Japanese ceramicist, makes the vases.

“That's why they have a very beautiful form. We work together on the form,” he says. “We share drawings and figure out how we want it to look. And then he goes away and makes them … typically to bisque and then I glaze them and then smash them and repair them.

“Doesn't seem to bother him too much.”

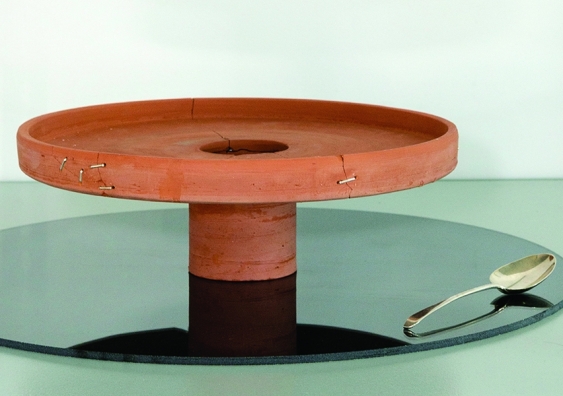

Jugaad Plate, repaired with sterling silver rivets, cut from a Georgian serving spoon (2017), Guy Keulemans, Kyoko Hashimoto & Trent Jansen. Terracotta, Georgian silver, rabbit skin glue. Photo: Lee Grant, courtesy of Nishi Gallery, Canberra.

Repairing Trent Jansen's Jugaad Plate (2017)

Designer Trent Jansen, a colleague from UNSW Art & Design, travelled to India in 2016 to collaborate with local potter Abbas Galwani in Dharavi, Mumbai. He was exploring the Australian philosophy of make do, with a cultural twist. Jugaad in Indian is “doing just enough with what you have, and it is also figuring it out as you go”, Dr Jansen says, “improvising”.

When he approached Dr Keulemans to repair a plate broken en-route to Australia, that improvisation continued.

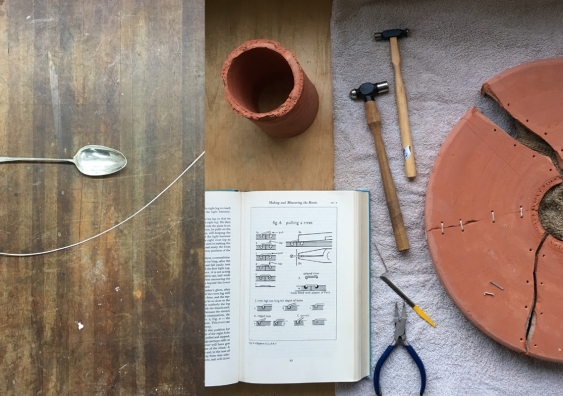

“I’d become increasingly interested in the stapling method which was actually the main way of repairing ceramics prior to the 20th century,” Dr Keulemans says. “But we’ve collectively decided to forget that as part of our material culture and it’s almost non-existent now, although it was fairly common a hundred years, eighty years, seventy years ago.

“It wasn’t the easiest thing to learn but there was a fantastic textbook that we found and we stapled it back together.”

Jugaad Plate, repaired with sterling silver rivets, cut from a Georgian serving spoon (2017), Guy Keulemans, Kyoko Hashimoto & Trent Jansen. Process documentation. Terracotta, Georgian silver, rabbit skin glue. Photo: artist.

“It was an interesting project too because that Jugaad plate already had a kind of a cross-cultural origin, being an Australian designer working with an Indian potter, and then by adding the stapling, which originated in China but became very popular in Europe, it adds this kind of third dimension of global hybridity,” Dr Keulemans says.

“And the fact that we chopped up one of my mother’s sterling silver tablespoons was fun too.”

The project is one of a series of collaborations with his wife and design partner Kyoko Hashimoto, a Japanese Australian designer whose primary practice is jewellery making. Their shared interest in the personal and cultural histories of objects, and the geological histories of the materials used, lays the foundation for a tactile, intuitive and experimental partnership.

Ritual Objects for the Time of Fossil Capital (2018), Guy Keulemans & Kyoko Hashimoto. Collection at left, detail at right. Various plastics from old toys chopped up, cement, sand, oxide, polymer rope from fishing vessel nets, steel cable, resin. Photo at left: National Gallery of Victoria. Photo at right: Makiko Ryujin.

Ritual Objects for the Time of Fossil Capital (2018)

The decision to make the Buddhist prayer beads in Ritual Objects for the Time of Fossil Capital (2018) using waste materials from the Keulemans’ children’s toys came from a desire to “ameliorate personal anxiety about giving plastic toys to our children,” he says.

“We actually try not to, but we have had lots of well-meaning family members who love buying them plastic toys. And you see how fragile these things are, how quickly they break, as fun as they can be for, you know, a few days or a week or a month.”

That parental concern for personal waste extends to a parental concern for the environment, he says. The prayer beads offer a non-didactic way to bring these issues up.

The Daizuju, or the Buddhist prayer bead, “is about reflecting on human weaknesses and the passions,” Dr Keulemans says. So this form contributes an “underlying Buddhist framework [to the piece] – although I'm not terribly religious, but I do find comparative religion very interesting.”

Daijuzu (Large Prayer Beads) (2019), Guy Keulemans & Kyoko Hashimoto. Concrete, steel rebar. Photo: Romon Yang.

Daijuzu (Large Prayer Beads) (2019)

The Daijuzu (Large Prayer Beads) uses the same typology. “It’s the same kind of religious artefact but much, much bigger. And the reason it's bigger is because we were dealing with a very specific problem, which is the use of steel reinforcement in concrete, and this is – unbelievably – this is a massive problem that is almost universally denied or ignored by the concrete industry,” he says.

“Obviously, some specialists have realised [steel-reinforced concrete] has a big problem but … most other people in the industry refuse to engage with [this].”

As a material concrete is incredibly energy-intensive to extract and manufacture, he says. “It's a massive contributor to carbon emissions, and therefore, climate change. And if it was used in a good design application, it could last for thousands of years.

“In fact, the Romans have developed concrete buildings that are still around 2000 years later, like the Pantheon in Rome, for example.

“But when you put steel reinforcement on the inside, and of course they are very good engineering reasons for doing that, but when you do that you make that concrete highly obsolete. I mean, highly obsolete is a relative thing. But for a building that has a potential lifespan of 2000 years, you're bringing it down to 50 years, 100 years, 150 years, something along those lines.”

Daijuzu (Large Prayer Beads) (2019), Guy Keulemans & Kyoko Hashimoto. Concrete, steel rebar. Photo: Romon Yang.

This means many early 20th century, multistory infrastructures are already compromised, he says. “That's not universal… there's a lot of factors involved, like proximity to the sea, the concrete mix of the time, the engineering quality, but there are big unknowns around that.

“So we don't know what kind of problem we're going to be facing. But many estimates are expecting that this will cost the US or the Australian economy trillions and trillions of dollars in expensive rebuilding in the late 21st and 22nd century.

“Yeah, so anyway, that's a huge problem, right? … So that also led me to a giant form. I thought, well, it is such a big problem, then maybe the form of that ritual necklace should be very, very big as well. And that kind of fit in with the other works that were in that particular exhibition being a concrete exhibition [with] a large number of big, big works.

“So it kind of had to stand out and have its own kind of visual presence for that purpose.”

Plinth 1 & 2 (2019), Guy Keulemans & Kyoko Hashimoto. Plywood, paint, glue, acrylic. Photo: Carine Thevanau.

Plinth 1 & 2 (2019)

While Dr Keulemans considers design his primary discipline, he is increasingly exhibiting in art galleries and art institutions. “Some people would call the work that I do design art, which is a bit of a clumsy term, but it kind of applies.”

When he was invited to contribute a new work to the inaugural group show at the Gallery Sally Dan-Cuthbert, an experimental designer homewares gallery, the first of its kind in Australia, “I thought, “Well, what can I bring to the art world that is kind of provocative?” he says.

“And I had the feeling that although there's a big movement of sustainable design, and almost every single designer that I know that's affiliated with a university, or a high level of practice, is aware of the importance of sustainability and includes it some way in what they do, the same isn't necessarily true for the art world.”

The plinths beg the question of the need to design, to create art, at all but particularly without sensitivity to its consequences for the planet, he says.

Plinth 1 & 2 (2019) details, Guy Keulemans & Kyoko Hashimoto. Plywood, paint, glue, acrylic. Photo: Carine Thevanau.

Plinth 1 & 2 foreground the environmental cost associated with art and design practices that comes from the translation of natural resources into end products. One plinth exhibits nothing; the other exhibits waste, waste that has been “sawn, hacked and milled from the plinths” themselves.

“It's like, well, what would you design if you were designing for an art gallery?” he says. “The designers always do the plinths, right? But what if those plinths had this kind of embodied message about the problem of waste and maybe some kind of reflection on circular design.

“Artists probably believe that they need absolute freedom of concepts in their work. So if they're pursuing one particular conceptual direction, they can't necessarily bring in a sustainability aspect or concept into that, and particularly into the manufacturing,” he says.

“But I kind of disagree with that. Because I think actually, if you look at the scale of art world production around the world, it's massive. The total valuation of the market is over USD$60 billion, so you can just imagine the carbon emissions of its production and shipping. So it can't just kind of get a free pass.

“No designer, maker, producer or artist can avoid a scrutiny of practice.”