A Soft Matter scientist's squishy quest to understand how life began

National Science Week: Meet UNSW's Dr Anna Wang who is trying to build a cell from scratch.

National Science Week: Meet UNSW's Dr Anna Wang who is trying to build a cell from scratch.

Up until the age of eight, Anna Wang originally thought she’d be a chef, but it was school visits by Dr Karl Kruszelnicki that first got her interested in science.

“I was sick (with bronchitis and migraines) and home from school watching TV a lot. And what was on TV were shows like Days of Our Lives and cooking shows. I knew what chefs were and I liked food.”

The daughter of Chinese migrants grew up in Mount Druitt in western Sydney before moving to the Inner West.

She remembers playing with her cousin, who also grew up in her grandparents’ Lilyfield house; not seeing many Asian people at her school “so it was a bit rough in that sense”; good friends and teachers; and watching TV shows in Chinese and English.

Anna Wang's love for dance started with ballet at age 6, and now includes more free-form styles like salsa. Photo: Supplied.

Attending the same school was science communicator Dr Karl's children.

“He would come in a couple of times a year and tell us weird science stories and I always found those really exciting. I liked the curiosity-driven side of science and I think that’s the thread that’s persisted all through my life.”

Her parents didn’t go to University but “they see the world in a technical way” and as she went through school, she started really enjoying mathematics and science.

“My main love was actually mathematics – I loved the abstractness of it, found it very hard especially in the later years at University, but I didn’t care about how hard it was, I just loved the process and the beauty of it.”

She was grateful for the support of Sydney Girls High School because “there was no such thing as “boys’” subjects, we just did what we wanted”.

“I am really grateful for that in retrospect because even as I got to university and saw that most of my physics and mathematics classmates were male, I didn’t really register that as problematic…I was unusually blessed in that sense, I’ve gone through so much schooling in a male-dominated field to have never felt that discrimination.”

The Soft Matter scientist initially chose to study Medicine at The University of Sydney.

“Although I enjoyed studying science I didn’t know what a career as a scientist was," she says.

"By contrast, I certainly knew what a doctor was.

"My family had many mysterious health issues so being a medical doctor seemed like a good idea,” she says, adding that her family were terrified by anecdotal evidence about scientists migrating to Australia and ending up as taxi drivers.

She enrolled in a combined Science/Medicine graduate program, “to put off the career decision a bit longer”.

But then she started doing small research projects with academics.

“Some of them were super cool…but I still couldn’t see myself doing them on a day-to-day basis. But what I did start seeing was what being a scientist really meant.”

She helped out on a project involving rabbits having heart attacks, a summer research project on nutrition, and dabbled in physics, trying to model protein aggregation “to study things like Alzheimer’s”.

But an undergraduate project with A/Prof Maryanne Large that captured her imagination was working with light.

“Optical fibre research, how you manipulate light into little tubes and make useful devices.”

Intrigued and spurred by excellent mentorship, Dr Wang took the plunge and left Medicine to do a PhD in Applied Physics at Harvard with Prof Vinothan Manoharan.

Dr Anna Wang graduated with a PhD in Applied Physics from Harvard University in 2016. Photo: Supplied.

“My PhD research was in a field called Soft Matter, and that’s trying to understand things that are squishy.

“We know that physicists work with lasers or hard material, but they also work on soft materials too.”

At Harvard, Dr Wang used holographic microscopy to research everything that is squishy, like gels, cells, food and paint.

“(During my PhD) I stared at one microscopic particle at a time for six years. It sounds completely nuts, but that’s what research is like.”

She says she loved applying the rigour of physics to understanding “messy, complex systems”.

“And when you are in the world of soft materials, it turns out that the actual molecules that you are dealing with really matter," she says.

"So there is a lot of research overlap with chemistry and chemical engineering – in research the fields all meld together.”

During her Harvard studies she used the technique of holographic microscopy, “which is literally like taking holograms and analysing them on a computer”.

The aim was to take better 3D images so that scientists could do better analysis.

“Most microscopes can only take photos in 2D," she says.

"With my lab mates I was able to help take algorithms developed by NASA to study the atmosphere and link it with lots of code to extract information from the holograms that we were taking on the microscope."

"It enabled me to study fundamental science problems, and even collaborate with the cosmetics giant Chanel.”

Soon enough she could watch bacteria swim around really fast frame rates, watch them change directions, run and tumble.

The research was useful for biological systems and she’s continued to use this technique in her research to this day.

After Harvard she completed a NASA postdoctoral program fellowship in astrobiology at Massachusetts General Hospital.

In the Fellowship, Dr Wang worked with 2009 Nobel laureate in Medicine, Professor Jack Szostak, to think about the emergence of a truly complex system - how life could have originated from simple chemicals.

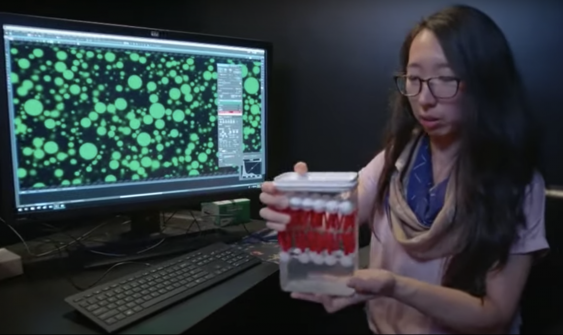

Anna Wang was featured on the prime time science series NOVA on US television channel PBS earlier this year, making soap and imaging artificial cells in the Szostak Lab. Photo: Courtesy PBS NOVA.

"I was enamoured with the idea that we could throw together some chemicals in the lab and that they would self-assemble into something that would look like a cell," she says.

But it is incredibly hard to build a cell from scratch.

“What we are trying to do is mimic life-like behaviours. If you create an artificial cell, how can you get it to move around, how can you get it to grow and divide?”

Three years ago, Dr Wang arrived at UNSW, and now leads her own research team as a Scientia Senior Lecturer in Chemistry.

“I decided that the way I could contribute to this field of research was by thinking about the cell membrane," she says.

"Cell membranes are well conserved across almost everything that we consider alive or half alive on earth: the virus behind COVID has a membrane, all our cells have membranes, plants, bacteria all have membranes.”

Inside these membranes you can trap RNA and protein.

“What we’ve been working on is getting these systems to grow and divide, let the right things in and the right things out, like taking nutrients in and getting rid of waste," she says.

"And once they make these little packets that have these behaviours, we can start building more complex systems.

Read more: 'When everyone is looking at the fish, I'm looking at the rocks'

“If we understand how the molecules come together, then we can have a level of control over what we’ve built with these molecules.

"If we can build artificial cells, then we can start making better designed compartments for drug delivery, we can make tiny microreactors that can churn out chemicals which might be suitable for therapeutic purposes.”

But her biggest reason to study these artificial cell systems is to understand how life could have started on Earth.

At hot springs in New Zealand with UNSW PhD student Luke Steller during a television shoot for ABC's Catalyst program last year, which investigated the complex geological processes that happened on early Earth. Photo: ABC Catalyst.

“It’s one of the big outstanding questions in science, and we have no idea whether we are alone in the universe. Hopefully not… but being part of the community trying to figure that out…is really exciting.”

She says there is big misconception that science is absolute. “It isn’t, it’s something that’s always changing and moving, and that in essence is what science is."

"It’s a way of understanding the world that is constantly being updated by evidence.

"I think the public understanding of that is improving…what scientists are really trying to do is just solve really hard problems and the process can be really tedious and take a lot of time and effort.

"The target might even be moving, but it is always worth getting to.”

Dr Wang says while she is a Chemist, whose formal training is in Physics, she prefers to call herself a Soft Matter scientist, who also lectures in undergraduate chemistry.

She says she is most passionate about seeing young minds grow.

“I really enjoy the process of them taking in new knowledge and seeing the world in a slightly different way…everything I teach is something that can be applied to the real world, and chemistry is really great for that," Dr Wang says.

"It’s in the kitchen, it’s in our food, it’s in us.

“They’ll understand why the sky looks red after a bushfire or why a replacement for gluten in gluten free bread works better than something else.

"I enjoy seeing my research students in my lab become independent investigators…the influence over young minds is very humbling.”

However she is distressed by how there is still a lack of women in science, engineering and mathematics.

“There’s a giant gap in my understanding of what’s happened in society. Obviously there are still barriers to people wanting to become a scientist…whether that’s related to socio economic or gender or ethnic background, it is quite a shame and needs to be addressed.”

Dr Wang playing the carillon at UC Berkeley. Photo: Supplied.

Outside lab life, she enjoys a range of activities like cooking, drawing, dancing, and indoor rock climbing. “I’m decent enough to really get joy out of them.”

Music is also a big part of her life. Growing up, she played piano and has an Associate Performance Diploma in Piano.

“I didn’t play everyday but it was a good emotional reset. Instead of a teen playing loud music, I just played the piano.”

As an undergraduate at Sydney University, she played the biggest instrument in the world, the carillon.

“It looks like a gigantic xylophone but you bash it with your fists and feet…I do love it, it’s a bit awe-inspiring.”

A big part of the reason she did science was the travel element.

“Going to conferences and meeting people from around the world, it always helps to see these different perspectives…I enjoy that global interconnectedness of science.”

Her advice to future scientists is to study what you want to study now, learn the higher-level skills of problem solving, how to learn, and team work, and fill in the specific knowledge gaps later.

“Find the right environment that makes you the most curious and well-supported and then there will be great things…then you will be well equipped to solve any problem.”

Dr Wang's sketch of Chip the dog. Photo: Supplied.