Islamophobia as a moral bludgeon

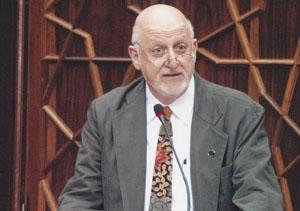

The catchcry of Islamophobia is used to silence legitimate debate and to imply that any unwelcome comment about anything to do with the Islamic tradition is unwarranted, argues Clive Kessler.

The catchcry of Islamophobia is used to silence legitimate debate and to imply that any unwelcome comment about anything to do with the Islamic tradition is unwarranted, argues Clive Kessler.

OPINION: We have again seen rage's ugly face glaring into ours. And again we have been advised by some that, if we do not want to see more rage, we must overcome our Islamophobia.

And, hearing that, many of us feel guilty. Or at least wonder whether some contrite self-examination might be timely and warranted.

As we do, the accusation achieves its desired effect. Our attention is displaced.

Looking inward, we fail to see how, minted as a polemical weapon, the term "Islamophobia" is used against those who doubt Islam's entitlement to a special kind of public consideration. Or to suggest that anyone who might question anything done in the name of Islam by any of its zealous defenders must be a bigot.

All religions, cultural traditions and the civilisations grounded in them contain elements that are less than exemplary and edifying. None is unadulterated moral ambrosia. Of ancient origins and shaped by long historical development, these features cannot be simply changed, excised or removed.

The question, rather, is how modern people are to construe and live with them. To start, they are to be acknowledged, not denied; examined historically and probed ethically, not made the objects of embattled cultural or sectarian protection. Of all these awkward cultural and moral inheritances, those that are of a sacred character or religious origins are especially sensitive and fraught.

Yet these days, and in our kinds of culturally complex societies and globalised humanity, it cannot be acceptable to take literally, and insist upon, the Hebrew Biblical injunctions that all heathen places of worship situated on what might later be deemed sacred ground must be torn down and utterly destroyed (e.g., Deuteronomy 7:5 and 12:2-3); nor for some Christians still to suggest, as in Mel Gibson's blockbuster movie, that Jews are "Christ-killers", forever cursed for their deicide.

Similarly, it must be impermissible in our time and circumstances for Muslims to uphold and publicly act in zealous self-righteousness upon any literal construction, born of scripturalist doctrines of the "inerrancy" of sacred texts, that, for their impiety and defiance against God, the Jews were "turned into monkeys and pigs", and so are forever to be despised and rejected (e.g., al-Baqarah 2:65 and al-A'raf 7:166); or that, when vouchsafed by God with the first version of the divine monotheistic revelation, the Jews treated it with contempt and incomprehension, choosing to carry what God had given them as a donkey carries a load of books, not appreciating their meaning and value but seeing them only as a burden (al-Jumu'ah 62:5).

There is a principle in the law of equity that he who comes to court must do so with clean hands. A similar moral obligation and constraint applies here in the court of democratic public opinion and multicultural, interfaith "discourse ethics".

Those who wish to uphold the term "Islamophobia" and make their own collectively self-protective and strategic use of it need to be sure that -- and might be entitled to do so only when -- their own religious traditions (and, more to the point, how they themselves interpret and promote them) are entirely free of any adverse, dismissive, disrespectful, hurtful or scandalising characterisation of the religious faiths of others.

You cannot impugn others unless you are yourself beyond reproach in these same matters.

Use of the term "Islamophobia" as a catchcry and moral bludgeon is now ubiquitous and inescapable. It has become the rhetorical "weapon of choice" not only of many beleaguered Muslims but, with scholarly endorsement and immense "cultural authority", by the exponents of hegemonic postcolonialist orthodoxy.

Routinely, we are these days made spectators or targets of its use to inhibit and even silence any serious discussion -- especially much needed serious and responsible public discussion -- of the historical development of Islamic civilisation and "the Islamic tradition" -- religious, legal, cultural, political and intellectual.

The term "Islamophobia" and its currently often indiscriminate use serve to imply that any unwelcome, and potentially adverse, comment about anything to do with the Islamic tradition, its evolution and the stance of any or some of its current adherents is unwarranted. It also implies that such commentary is pathological, the sign of a disturbed, warped and morally twisted mentality, one that need not and must not be heard but instead refused and abominated.

The suggestion that any such comment is democratically impermissible -- which is what the intimidatory use of the term Islamophobia achieves -- is excessive and exceptional.

Those who now use accusations of "Islamophobia" to silence necessary public consideration of the evolution of the Islamic civilisational tradition and its modern legacy, and to defend by rhetorical intimidation some of its more questionable aspects, must address those arguments substantively. And honestly.

Never has the need for genuine interfaith dialogue, as distinct from special pleading, been more urgent. Name-calling and tribal abuse, noisy recourse to the rallying war-chant "Islamophobia!", simply will not do.

Clive Kessler is an Emeritus professor of Sociology and Anthropology at UNSW.

This opinion piece first appeared in The Australian.