Explaining Schwarzenegger - men, biceps and getting what you want

A new study has found a link between the upper-body strength of men and their attitudes to the redistribution of income and wealth in modern society, writes Professor Rob Brooks.

A new study has found a link between the upper-body strength of men and their attitudes to the redistribution of income and wealth in modern society, writes Professor Rob Brooks.

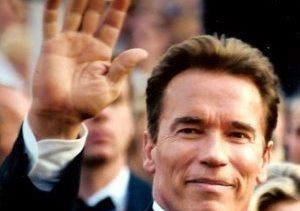

OPINION: This weekend I gained a grudging appreciation for Arnold Schwarzenegger. The Governator, not the Terminator.

Having watched Arnie’s political rise and fall from afar, he always seemed an odd chimera. Lines he’d delivered as the Terminator retrofitted to an ideology he’d borrowed from somebody else. A kind of populist piss-take exploiting name recognition among cinema-going-yet-politically-comatose voters.

But I’ve just read a paper that made Arnie slightly more intelligible to me. Entitled “The Ancestral Logic of Politics” the paper published last week in Psychological Science explored the link between male upper-body strength and assertion of economic self-interest.

The link between what and what?

Exactly.

The short story is that men with big biceps and who are relatively poor tend to be strongly in favour of social welfare, wealth redistribution and other economic programs associated with the political left. More so at least than equally poor but puny men. Whereas the exact opposite is true for wealthy men: the bigger the biceps the more right-leaning the inclination to economic redistribution.

Rational self-interest

In order to understand this finding we need to consider why people take on the political views they do. While people’s politics are shaped by many factors, self-interest is thought to be particularly strong. That’s not to say voters care only about themselves. But rather that an element of self-interest shaped their views.

With this in mind it isn’t hard to see why policies of social welfare and economic redistribution tend to win more support from the poor – they have much more to gain. Likewise, the twin obsessions of plutocrats – slashing spending and cutting taxes – really mean cutting expenditure on welfare and eliminating taxes that redistribute resources to those less fortunate or well-endowed.

If political views are forged out of rational self-interest, then attitudes to redistribution should follow a neat left-right divide, everything else being equal. But they seldom do.

The new paper, by Michael Bang Petersen, Daniel Sznycer, Aaron Sell, Leda Cosmides and John Tooby adds an interesting twist that might explain why the left-right distinction gets so very blurry.

They argue that for most of humanity’s evolutionary past, the biggest, strongest men were best able to assert themselves in negotiations, wrangling outcomes in their interest. Studies of negotiation and conflict in animals show that better fighters consistently gain a disproportionate share of any resource – without having to fight for it. Most negotiations are an ‘Asymmetric War of Attrition’ in which violence need not be deployed but only implied. The possibility of violence alone leads others to concede more than their share.

That’s where the expression “the lion’s share” comes from. Lions contribute little or nothing to most hunts, leaving the hard and dangerous work of killing prey to the lionesses. The lion then moves in and takes as much as he likes – and there is very little any lioness or cub can do about it.

People astutely judge the fighting abilities of other men – mostly by paying attention to upper body strength. And bicep size provides a most conspicuous, reliable cue of upper body strength.

Psychologists have repeatedly shown that men with greater upper body strength feel more entitled to having things go their way. And they become aggressive more easily. The same does not seem to apply – at least not to the same extent – among women.

The link between male upper body strength, fighting ability and dominance is nowhere near as strong today as it has been throughout our evolutionary past. And democratic processes ensure that strong men can no longer wrest political outcomes in their own interest. Or at least they can’t do so by brute strength alone.

Petersen and colleagues argue that we retain many of the psychological mechanisms whereby strong men assert themselves, and weaker men are more likely to concede. And that shows up in the conviction with which stronger and weaker men hold political views that are in their rational self-interest.

But the result does not apply among women.

Interestingly they repeated the same study in three countries: The USA, Argentina and Denmark. The pattern held in all three, although it was weakest in Denmark. I wonder if the lower income inequality in Denmark, and the social benefits of Danish social welfare programs have eroded the link between physical strength and convictions about redistribution?

Am I a robot?

This paper embodies the kind of evolutionary psychology that routinely gets people’s backs up. We often believe our convictions are reasoned, rational and reasonable. To be told that deeper motivations of which we are not even aware might sway our ideologies and beliefs can be awfully confronting.

The authors are not claiming that attitudes to economic redistribution are settled, hard-and-fast by some combination of socioeconomic status and bicep size. The value of this paper is in showing how our evolved biology and our contemporary politics can interlink in interesting ways, creating nuanced individual differences.

Readers of this column will be familiar with my obsessive interest in the links between biology and ideology. Particularly in the sphere of sex and reproduction, where insecurity over paternity, conflict between spouses and divergent attitudes regarding the regulation of fertility all generate deep political currents.

Readers will also know how I despise the idea that biological effects are “hard-wired” (a particularly dull computing metaphor for human behaviour) or immutable. The beauty of evolution, for me, is in the subtle play between biology and environment. Which is why I’m delighted that this simple (though logistically demanding) study has revealed yet another way in which evolved biology adds nuance to our understanding of political behaviour.

I am already thinking about how to measure the importance of the bicep-redistribution link relative to other influences on political attitudes. And about how to dissect the basis for the link?

Does going to gym reshape a man’s political outlook? Or do men more interested in asserting their self-interest politically tend also toward bicep-building exercise regimes?

And does one measure the bicep on the right or the left?

Arnie, the Republican

Arnold Schwarzenegger’s politics should never have surprised me. He may have played the fictional underdog Conan the Barbarian, but his speech at the 2008 Republican convention revealed that Arnie, since he first picked up a dumbbell in Graz, has been about the muscular, assertive kind of masculinity so beloved of Republicans and the right in general:

I finally arrived here in 1968. What a special day it was. I remember I arrived here with empty pockets but full of dreams, full of determination, full of desire. The presidential campaign was in full swing. I remember watching the Nixon-Humphrey presidential race on TV. A friend of mine who spoke German and English translated for me. I heard Humphrey saying things that sounded like socialism, which I had just left. But then I heard Nixon speak. He was talking about free enterprise, getting the government off your back, lowering the taxes and strengthening the military. Listening to Nixon speak sounded more like a breath of fresh air. I said to my friend, I said, “What party is he?” My friend said, “He’s a Republican.” I said, “Then I am a Republican.” And I have been a Republican ever since.

Professor Rob Brooks is director of the UNSW Evolution and Ecology Research Centre.

This article was originally published at The Conversation. Read the original article.