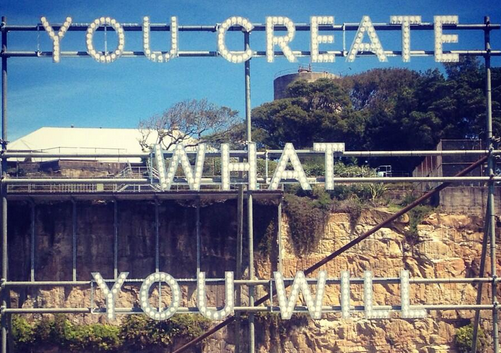

A first look at the 19th Biennale of Sydney

The Sydney Biennale is an occasion for significant cultural exchange between artists and is well worth visiting, but lovers of the contemporary will find the Adelaide Biennale more compelling, writes Joanna Mendelssohn.