Ten kilos of first world war grief at the Melbourne Museum

Melbourne Museum’s new exhibition, with its well chosen artefacts, tells the human stories of Australians in WWI, writes Peter Stanley.

Melbourne Museum’s new exhibition, with its well chosen artefacts, tells the human stories of Australians in WWI, writes Peter Stanley.

OPINION: The Melbourne Museum’s World War I: Love & Sorrow exhibition, which opens this weekend, explores the various experiences of Victorians in the Great War, and the war’s effects on them.

Museums have a hard job conveying often fleeting human interactions and experiences using their stock-in-trade – the artefact. How can you convey friendship or hatred through objects? What can you use to show fear, hatred, comradeship or idealism? How can a museum convey in an artefact what grief felt like?

WWI: Love & Sorrow tells the story of, among many others, the Roberts family, of Hawthorn and South Sassafras (now Kallista, in the Dandenongs). Their story embodies what this exhibition is about, and how museums can best tell human stories.

The Roberts family scrapbooks

The experience of the Roberts family was both unique and representative – and seemingly made for a museum. Indeed, in planning how the Melbourne Museum would reveal and explore how Victorians lived through the Great War – or not – their story became one of the “must haves”.

In 2009 I published Men of Mont St Quentin, a book that tried to show how one 12-man platoon (number 9, of the Victorian 21st Battalion) experienced the final attack on the German-held Mont St Quentin, the way it affected those who survived as well as the families of those who died in the attack.

In telling this story the papers of Garry and Roberta Roberts, preserved in the State Library of Victoria, were crucial. In fact, without them the experience of that platoon would have been indistinguishable from the other 60-odd platoons involved in it.

But among 9 Platoon that afternoon was a bank-clerk-turned-orchardist, Frank Roberts, Garry and Roberta’s eldest son. He died in the assault. The grief his father, especially, endured, and his manner of commemorating his son’s life has made him one of the best known bereaved fathers in Australia’s experience of the Great War.

The Roberts family was an unusual one. Solidly middle-class (they had a house in Hawthorn and a “weekender” in the hills), Garry was an accountant for the Melbourne Tramways Trust. They used their modest wealth to support the arts – C.J. Dennis wrote Songs of a Sentimental Bloke in the backyard at South Sassafras. Frank volunteered to go to war in 1916, soon after marrying his fiancée Ruby. By the time he left Melbourne Ruby was pregnant, and their daughter, Nancy, was born just as Frank reached the front, late in 1917.

The Roberts family never doubted that Frank had done the right thing, but their commitment to the war was tested by the news that arrived on 13 September 1918 that Frank had been killed.

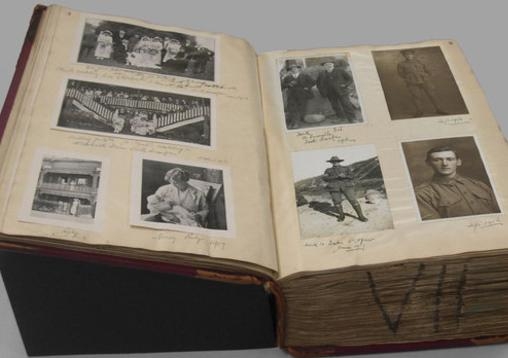

Garry described this in his diary as “the most awful day of my life”. He had obsessively documented his children’s lives (and much besides) by creating massive scrapbooks. He dedicated two of these huge volumes to Frank’s military service and his death.

He collected newspaper clippings and photographs, and persuaded most of the survivors of Frank’s platoon to write an account of the day of his death. That’s what helped me write my book: the survivors’ accounts are the single most detailed description of one day in Australian military history.

A record of grief

The grief of the Roberts family is indescribable. We can imagine Garry sitting into the night, reading and annotating the scrapbook he had made. But we cannot literally share his grief.

What we can do is visualise it by seeing the sheer size of one volume of Garry’s scrapbooks. They are nearly a metre tall; up to ten kilograms in weight; with every one of up to 500 pages bearing letters and illustrations, pages cut from books and – over-and-over again – copies of the “In memoriam” card Garry had printed bearing Frank’s likeness. PIC?

Ruby, Frank’s widow, was of course distraught. Her grief can be seen in a pair of baby shoes – Nancy’s. She sent one tiny shoe to Frank, writing that they would be reunited when he came home. The bootees were reunited; but Frank and Ruby and Nancy were not. A pair of pink baby shoes represents, more powerfully than all the medals and medallions and sympathy cards, what the victory of Mont St Quentin cost this one Melbourne family.

And here’s the point: 19,000 Victorians died in the Great War, most, like Frank, in the great battles on the Western Front. The Roberts family was unusual in the lengths Garry went to record and express his grief; but he was hardly alone in feeling it.

Looking at the bulky scrapbook that Garry created as a paper memorial to his son, we can get a sense of the weight of grief that he and all bereaved parents carried. And looking at Nancy’s tiny bootees we can glimpse the war’s effects on that little girl and her mother.

This is what museums can do with a caption and a few well-chosen artefacts.

Peter Stanley is Research Professor in the Australian Centre for the Study of Armed Conflict and Society at UNSW.

This opinion piece was first published in The Conversation.