The Photograph and Australia: the curator and the exhibition

A major retrospective of Australian photography at the Art Gallery of NSW has produced a cool yet passionate argument on the very nature of Australia, writes Joanna Mendelssohn.

A major retrospective of Australian photography at the Art Gallery of NSW has produced a cool yet passionate argument on the very nature of Australia, writes Joanna Mendelssohn.

OPINION: The opening room of The Photograph and Australia, a major retrospective of Australian photography that opened at the Art Gallery of NSW on the weekend, says it all. Two walls are massed with portraits large and small, of photographers. In artspeak terms this is a classic “salon hang”, the kind of crowded wall that would confront visitors to the Academy in the 19th century.

There is no hierarchy with these works: they are all makers and manipulators of images. By placing them here, at the entrance, the curator, Judy Annear, is telling the viewer that what is to be shown will be seen through their eyes.

They gaze not just at the viewer but at two of visiting American photographer Melvin Vaniman’s late 19th-century panoramas on the opposite wall – one of the intersection of Collins and Queen Streets Melbourne, and one of the Blue Mountains scenery at Leura. These two images encapsulate the land that the photographers describe and interpret, and through their interpretations we, the people, can learn more about ourselves.

As Judy Annear makes clear in her catalogue introduction, the scholarship supporting this exhibition stands on the shoulders of those curatorial giants who first collected and exhibited Australian photography. What Annear has produced is not a historical overview of a great photographic panorama, but a cool yet passionate argument on the very nature of Australia and its primary concerns.

This is a large exhibition, yet every work is so carefully placed in relation to others that suddenly new connections are made evident. It is worth allocating several hours to see how lines of sight and apparently accidental conjunctions give new insights.

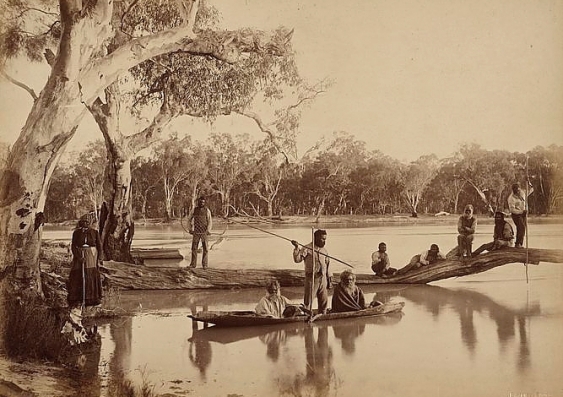

The exhibition is underpinned by Annear’s awareness of the deep scar of the impact of colonisation. The earliest photographs on view date from the 1840s, less than a decade after the inventions of Henry Fox Talbot and Louis Daguerre.

These oldest photographs are placed in display cases in the large central court, where the soaring ceilings usually inhibit displays of small works. But nothing is as it at first appears. For these first photographs are objects made by the colonisers, the invaders, the possessors of land and people.

Works on view include Douglas Kilburn’s 1847 portraits of Koori men and women and Charles Mountford’s Dingo, from his album The Gesture Language of the Australian Aborigine, as well as miniature portraits of squatters and their extended families.

Soaring above them, as though they are looking down in consideration of the art of the colonisers, are two series of photographs by contemporary Aboriginal photographers. Tracey Moffatt, that great appropriator, is represented here by her series Beauties, a found photograph which she reprinted in different tones, in what can be seen as a homage to Andy Warhol (see main image).

Ricky Maynard’s series of ghost-like Tasmanian landscapes look down on Henry Albert Frith’s bizarre portrait group, The last of the native race of Tasmania (1864), where the exiles are uncomfortably clad in full Victorian regalia.

From this central room all later truths flow. There is Simryn Gill’s Eyes and Storms, placed next to earlier photographers have lovingly recorded the magnificence of nature and the progress of science. But Gill’s landscapes show what happens to nature in Australia after it has met mining; the result is rather too close to James Short’s photograph of the moon.

Then Sue Ford’s self-portrait series shows her mature and age, from girl to woman in photographs taken in various formats over a 46 year time-span. Photographs can both capture time, and defy it.

They can also manipulate. Axel Poignant took a series of photographs of Aboriginal people in central Australia. For many people these images of dusty stockmen were the reality of modern Aboriginality. Annear has placed these images next to another reality: Mervyn Bishop’s photograph of Jimmy Little singing at the state funeral for Kwementyaye Perkins in 2000.

Bishop’s best-known photograph is on the opposite wall.

This is the image of the moment in 1975 when Gough Whitlam poured soil into Vincent Lingari’s hand, symbolising the return of their land to the Gurindji people. Bishop is one of the great documentary photographers and in 1975 he was working for the Department of Aboriginal Affairs as a staff photographer.

The photograph captures the hope of a new era. It is also a carefully staged image. Whitlam originally poured the earth into Lingari’s hand in the shadow of a tent. Bishop suggested blue sky would be a better background and both men agreed to repeat the action in the sun. Other, non-Aboriginal, photographers then stood back to enable the symbolism of Australia’s first Aboriginal news photographer recording a great moment of change for Aboriginal people.

It is appropriate that this hangs next to David Moore’s equally manipulated document of a 1949 Redfern interior. Even in the 1940s Redfern had a significant Aboriginal population.

While many of the works in The Photograph and Australia are precious limited-edition works, the truth is that the power of the photograph is that it is the kind of multiple that can be endlessly reproduced. The point is made in the exhibition with walls of postcards – but they were the product of 19th century technology.

Now images once carefully taken on glass plates and developed in darkness with magical potions are instantly relayed through the ether of the internet. In The Photograph and Australia, Annear makes a good argument for examining the images of the present in the light of that distant past.

The Photograph and Australia is on display at the Art Gallery of NSW until June 8. Details here.

Joanna Mendelssohn is an Associate Professor in Art & Design at UNSW.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.