Changing the conversation can lead to a better way on asylum seekers

Both major parties support offshore processing and boat turnbacks. But public opinion is not so clear-cut. And nor are the policy choices, writes Claire Higgins.

Both major parties support offshore processing and boat turnbacks. But public opinion is not so clear-cut. And nor are the policy choices, writes Claire Higgins.

OPINION: Debates on Australia’s policies toward asylum seekers have made an early appearance in the 2016 election campaign. Several current and retiring Labor MPs, as well as some candidates, have spoken out against the party’s support for offshore processing and turning back asylum-seeker boats.

Both major parties support offshore processing and boat turnbacks. But public opinion is not so clear-cut. And nor are the policy choices.

The issues in this campaign are similar to those in 2013: the prospect of further boat arrivals and the reality of people held offshore.

But since the last election, a policy of turning boats around has not guaranteed the safety of those who have been returned. And it has been inconsistent with Australia’s obligations under international law.

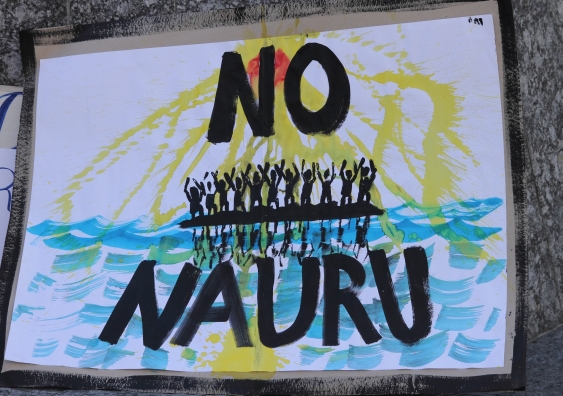

In the last three years, Australia’s arrangements with Papua New Guinea and Nauru have not secured sustainable, durable solutions for those found to be refugees. Some of the asylum seekers on Manus Island and Nauru have spent 1,000 days in detention, at a cost to their mental and physical health and at an estimated cost of A$400,000 per person per year.

Surveys consistently show that many Australians are in favour of restrictive asylum policy. A closer look, however, indicates that attitudes are not necessarily this straightforward.

There are strong misunderstandings or myths among Australians about asylum seekers. These are shaped by the language used in national political debate.

Voters are largely unaware that seeking asylum is legal, and that Australia has voluntarily committed to abide by international refugee law through signing the 1951 Refugee Convention.

This highlights the nexus between public opinion and policy in this field. A concern for community attitudes has underpinned Australian immigration policy since federation. Major reform has historically involved government efforts to secure public support.

Recent polling on the issue of asylum seeker babies and conditions in offshore detention shows public opinion is changeable. In recent research, many respondents who supported Australia’s treatment of asylum seekers said they did so because they were not aware of other policy options.

There is a wealth of expert opinion to draw from, as well as lessons from policies in place elsewhere.

Various mechanisms exist to expand humanitarian admission pathways, as well as other safe and legal avenues to access protection. Countries such as Brazil and the US, for example, have implemented procedures for orderly departure, which can allow certain people fleeing persecution in Syria or Central America to apply for protection without having to undertake a dangerous journey over land or sea.

The first step is to acknowledge that forced migration is an enduring phenomenon. Australia cannot unilaterally “fix” it. It requires a humane, lawful and co-operative policy approach.

An international perspective is essential to improving Australia’s asylum policy debate. The number of asylum seekers who arrive by boat has always paled in comparison with the numbers found elsewhere around the world. This is despite Australia spending twice as much detaining asylum seekers as comparable countries in Europe or North America.

The Australian government is taking several years to process the applications of almost 29,000 asylum seekers living in the community, due to various changes in the procedure for determining their claims. In Germany, where hundreds of thousands of people apply for asylum every year, authorities are taking between five to 11 months to process applications for protection.

If they are to be humane and effective, Australia’s policies must take into account the availability of protection for asylum seekers within the region. Turning back boats has done little to tackle this – as the recent arrival of a boat carrying suspected asylum seekers in the Cocos Islands demonstrates.

In the aftermath of the PNG Supreme Court decision declaring immigration detention on Manus Island to be illegal, offshore processing seems increasingly untenable. The need to find alternatives that acknowledge Australia’s responsibility for the protection of those held offshore is apparent. This provides an opportunity to begin an informed conversation about how Australia can better respond to refugees.

Studies show that Australian voters are more concerned about issues such as health and education than the arrival of boats. That said, voters have considered the issue of refugees and asylum seekers to be relatively important during the election years of 2001, 2010 and 2013, when boat arrivals were at higher levels and a subject of political debate.

This year, there are fewer boats but still plenty of talk. Changing that conversation could make alternative policies possible.

Claire Higgins is a Research Associate, Andrew & Renata Kaldor Centre for International Refugee Law, UNSW.

This opinion piece was first published in The Conversation.