The legend and laws of Anzac

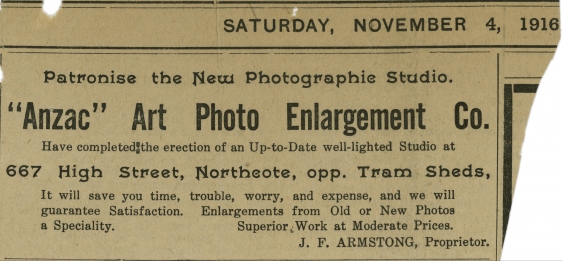

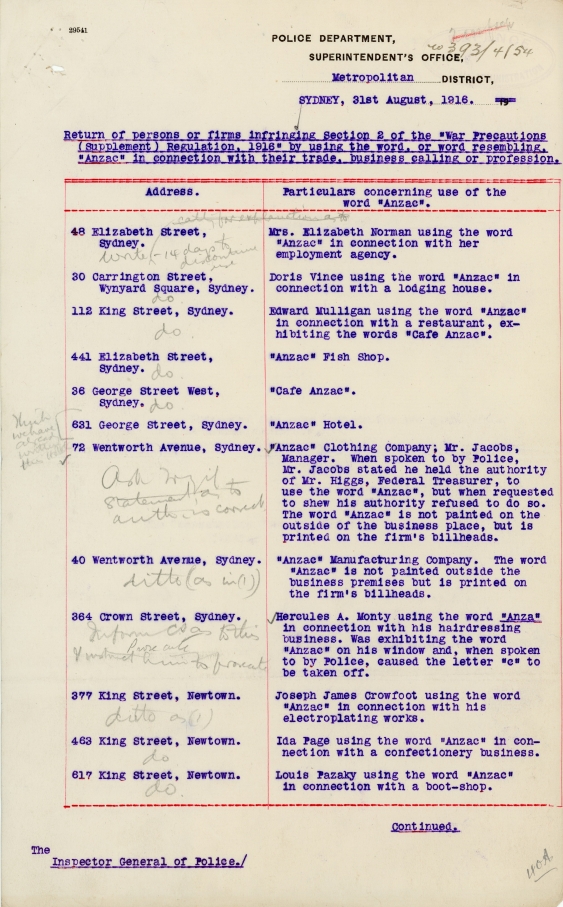

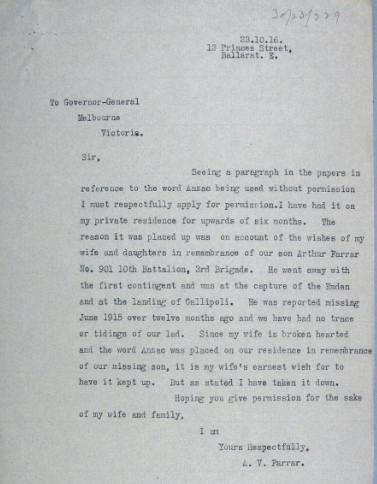

Within a year of troops landing at Gallipoli in April 1915, it had become an offence to use the word Anzac – or even a word similar to it – in trade or business. The impact has been chronicled in a new book by UNSW Law's Catherine Bond.