Explainer: how proceeds-of-crime law works in Australia

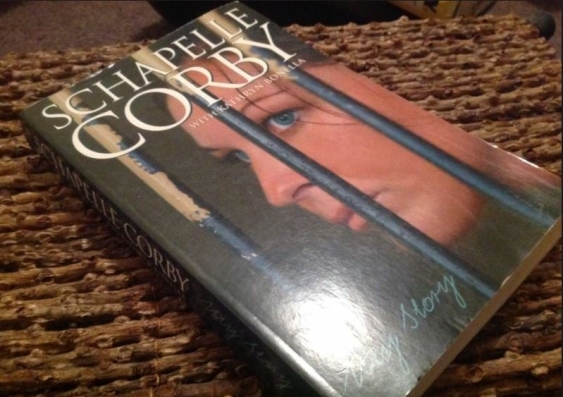

Proceeds of crime are covered by federal and state laws, both of which could apply in a case like that of Schapelle Corby, writes Nicholas Cowdery.

Proceeds of crime are covered by federal and state laws, both of which could apply in a case like that of Schapelle Corby, writes Nicholas Cowdery.

OPINION: The nine legal jurisdictions of Australia have a patchwork of laws directed at depriving criminals of the profits of their crimes. There are many similarities between jurisdictions, but the laws are by no means uniform.

Laws are directed towards assets used in committing a crime and those (including money) derived from criminal acts. The intention is to deprive criminals of their unlawfully used or acquired assets in a punitive way (thereby, hopefully, deterring them from offending in the first place), and to remove such assets from the pool available for further offending by them or others. Orders may also be based on a person’s otherwise unexplained wealth, which could only have been acquired through undeclared criminal activity.

Orders may be made against both the assets themselves and the offenders personally. The orders may be sought following criminal conviction or (except in Tasmania, apart from unexplained wealth) on a civil basis, where the standard of proof that someone has proceeds of crime is not as high.

Orders may be sought to trace, freeze, restrain, seize, confiscate and forfeit assets. Pecuniary penalty orders (fines set according to profits made) may be imposed.

Orders may also be made to seize the proceeds of the commercial exploitation of a person’s notoriety from criminal offending, literary or otherwise (but often described as “literary proceeds”).

There have been some high-profile cases of these. For example, those involving Mark “Chopper” Read (whose profiting probably contributed to the making of the present laws), former Guantanamo Bay detainee David Hicks and Schapelle Corby at an earlier time.

In the Hicks case in 2004, the Commonwealth Act was amended to (arguably) include an offence triable by the military commission – which convicted Hicks. To seek to remove any doubt, in 2007 South Australia amended the Criminal Assets Confiscation Act 2005 to catch any profit from Hicks’ sale of his story.

However, unless complementary legislation were passed, if Hicks published and profited in another jurisdiction the South Australian legislation would be bypassed. Liability under the Commonwealth Act may be another question.

These matters have become of interest again with the return of Schapelle Corby to Australia (specifically Queensland) from Indonesia. The Queensland Criminal Proceeds Confiscation Act 2002 provides for three civil schemes of recovery of criminal proceeds. These apply to illegal activity that includes a criminal offence committed outside of Queensland that is an offence in that jurisdiction or would be an offence in Queensland. Corby qualifies as having been involved in “external serious crime related activity”, and thus attracts the operation of the act.

The act provides for “special forfeiture orders” against a person convicted of a confiscation offence where the person, or someone acting on the person’s behalf, “has derived, is deriving, or is to derive benefits from a contract entered on or after 12 May 1989 about either” a “depiction of the confiscation offence … in a movie, book, newspaper, magazine, radio, or television production, or in any other electronic form, or live or recorded entertainment of any kind” or an expression of the person’s “thoughts, opinions, or emotions about the confiscation offence”.

It doesn’t matter where or when (after May 12 1989) the contract was made or when or where the benefit was derived or resides, so an offshore arrangement may be caught. There is no time limit on making an application for an order. The order may require payment to the state of “an amount equal to all or part of the [person’s] benefits under the relevant contract”.

If the benefit was realised outside of Australia, however, there could be practical problems in enforcing any order.

Commonwealth legislation could also apply in these circumstances: the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002. A “literary proceeds” order may be available. If a “foreign indictable offence” (defined so as to include Corby’s Indonesian offence) has been committed, application may be made for payment to the Commonwealth of any gain the person makes from its exploitation. This includes any media interviews, books, or other form of publication or entertainment. The benefit must be made to the person or to someone else at the person’s direction.

Significantly, in the case of a foreign indictable offence, “a benefit is not treated as literary proceeds unless the benefit is derived in Australia or transferred to Australia”.

In 2006, Schapelle Corby had a book published in Australia, My Story, and New Idea published an article about her. The Australian Federal Police tracked large payments for both from Australia to an Indonesian bank account controlled by her brother-in-law (from the book – over $250,000) and to her sister Mercedes (from the magazine article – $15,000).

The Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions (CDPP) obtained orders in the Queensland Court of Appeal under the Commonwealth Act that any such payments be made to the Official Trustee in Bankruptcy. As to a geographical nexus, the court held that “all that is required is that … the benefit has its geographic origin or source in Australia”. It held that literary proceeds were generated in Australia in consequence of the publication of the book and the article in Australia.

The CDPP applied for a permanent literary proceeds order, and by consent Corby was required to pay $128,800 to the Commonwealth out of the money then held by the Official Trustee in Bankruptcy.

It is therefore possible to imagine a contractual arrangement now for the benefit of Corby that might escape or at least limit the scope of the Commonwealth Act. However, the Queensland Act might still apply.

Provisions of the kind for literary proceeds orders have been criticised on the grounds that they interfere with the right to freedom of expression, discourage offenders from describing matters that may be useful to law enforcement, and remove an avenue of rehabilitation and expression of remorse for offenders.

But such criticisms miss the point. It is not the publication of stories that is sought to be penalised, it is offenders’ profiting from that activity.

Nicholas Cowdery is Visiting Professorial Fellow at UNSW.

This article was first published on The Conversation. Read the original article.