Vital Signs: the calm before the storm in US-China trade

While US President Donald Trump is now being advised by a heterodox economist, the effects of the ongoing trade war with China may take time to become evident.

While US President Donald Trump is now being advised by a heterodox economist, the effects of the ongoing trade war with China may take time to become evident.

Vital Signs is a regular economic wrap from UNSW economics professor and Harvard PhD Richard Holden (@profholden). Vital Signs aims to contextualise weekly economic events and cut through the noise of the data affecting global economies.

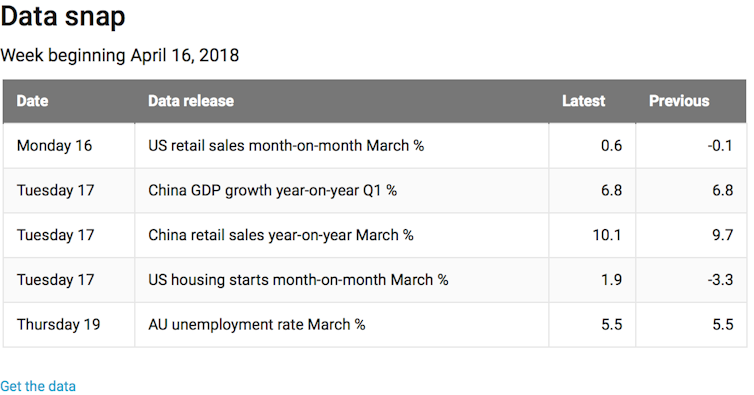

This week: the US administration continues it’s anti-trade rhetoric, China grows a little faster than expected, Australian employment figures underwhelm, and the RBA seems unperturbed by household borrowing risk.

It’s not all that often that the semi-annual report titled “US Treasury Macroeconomic and Foreign Exchange Policies of Major Trading Partners of the United States” is a hotly anticipated document. But against the backdrop of the Trump administration’s views on trade, it was this week.

The report was prepared by seasoned folks at Treasury, yet it has the fingerprints of the administration and its mercantilist views all over it.

Early on the report states:

“The global economy accelerated in 2017 to its fastest pace of growth since the post-crisis rebound in 2011. The broad-based strengthening of growth was led by the United States, where domestic demand growth averaged 3 percent over the last three quarters of the year, and by a synchronized expansion in Europe…Notwithstanding the pick-up in global growth, the U.S. trade deficit widened in 2017…

The Administration remains deeply concerned by the significant trade imbalances in the global economy, and is working actively across a broad range of areas to help ensure that trade expands in a way that is fair and reciprocal.”

“Fair and reciprocal”. Well that sounds nice. But US trade is fair and reciprocal. Imports from China allow the US to allocate its resources to what it does relatively more efficiently – make fewer t-shirts, produce more iMacs, iPhones and Apple watches, for example.

President Trump has long thought – mistakenly, mind you – that trade is a zero-sum game and that bilateral trade deficits are evidence of a “bad deal”. That’s flat out wrong. But given the president’s famously short attention span there was some hope those views wouldn’t affect policy too much.

Unfortunately, he appointed Peter Navarro as Director of the White House National Trade Council. Navarro thinks if trade deficits go down, economic output must rise – a conclusion that is false as a matter of logic. It’s distressing that Navarro doesn’t understand the principle of comparative advantage, or even how the national accounts work in that exports add to GDP, but imports leave it unchanged.

As a brief aside, Navarro is a self-described “heterodox economist”. Those folks in Australia who wear that moniker with pride would do well to reflect on how one of their intellectual fellow travellers is complicit in attacking the living standards of not only the poorest people in the US, but also in China.

Speaking of China, figures released this week showed that China’s GDP grew a little faster than expected, expanding 6.8% in the first quarter of 2018. This was largely due to strong consumer demand (which accounted for roughly 80% of that growth), but also strong exports and a healthy construction sector. Indeed, Chinese retail sales rose 10.1% for the 12 months to March, exceeding both their recent pace and market expectations.

Given time lags and implementation issues, the recent tit-for-tat tariffs between the US and China have yet to take effect – so next quarter’s numbers will be the really interesting ones to focus on. In fact, Chinese exports to the US were up 14.8% on an annualised basis, suggesting that exporters may have shipped goods early in a bid to beat the tariffs. That “pipeline filling” could result in a significant drop next quarter.

In the US, retail sales figures for March showed positive signs. Commerce Department data showed retail sales up 0.6% in March, a bounce back from previous disappointing monthly figures in 2018. Importantly, bellwether categories like cars and appliances were up strongly – a sign of consumer confidence.

Residential construction in the US was also strong, with housing starts up 1.9% to 1.32 million at an annualised rate, compared to market expectations of 1.27 million. This was driven, however, by so-called “multifamily” construction, which is essentially apartments. As in Australia, that is a volatile category month to month. It was up strongly, but had been down 10.2% in February. Single-family construction fell 5.5%, the largest decline in seven years. All in all, a mixed bag.

In Australia, fewer jobs were created in March than expected, with unemployment steady at 5.5%, seasonally adjusted. This is still far too high, and with the participation rate picking up it could head higher, rather than lower.

The RBA released minutes of its most recent board meeting.

The most interesting part was the discussion of financial stability of Australian households. The minutes noted:

“risks remained from the high level of household debt and the growth of riskier lending in earlier years, but regulatory measures had helped to contain the build-up of risks.”

They added that while household debt had outpaced income in recent years, net household wealth was also growing, with housing and financial assets of Australian households exceeding borrowing.

“Members noted, however, that this was not reflective of the financial positions of all individual households. Nevertheless, measures of household financial stress did not indicate a high level of financial stress at present.” (emphasis added).

It’s that italicised part that is important. Just because on average households might have their noses above water doesn’t mean significant problems don’t loom.

![]() It’s the marginal household or borrower that matters, and can drive financial problems. Think sub-prime in the US. Average borrowers in California or Massachusetts, or New York were fine. But the marginal borrowers were not, and it was their borrowing behaviour (and the behaviour of those who lent to them) that triggered the financial crisis. Surely the RBA understands that, using this to inform its approach to macroprudential regulation?

It’s the marginal household or borrower that matters, and can drive financial problems. Think sub-prime in the US. Average borrowers in California or Massachusetts, or New York were fine. But the marginal borrowers were not, and it was their borrowing behaviour (and the behaviour of those who lent to them) that triggered the financial crisis. Surely the RBA understands that, using this to inform its approach to macroprudential regulation?

Richard Holden, Professor of Economics and PLuS Alliance Fellow, UNSW

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.