Australia can do a better job of commercialising research – here's how

There are logical steps to bringing universities and industry into more productive collaboration, writes Ian Jacobs.

There are logical steps to bringing universities and industry into more productive collaboration, writes Ian Jacobs.

OPINION Australia can benefit much more than it does currently from the world-leading research in our universities. It ranks near the top of the OECD for research excellence but is less effective at collaboration between industry and researchers to drive the economic benefits of research. I suggest two important measures that could go a long way to achieving more translation of research to achieve commercial outcomes.

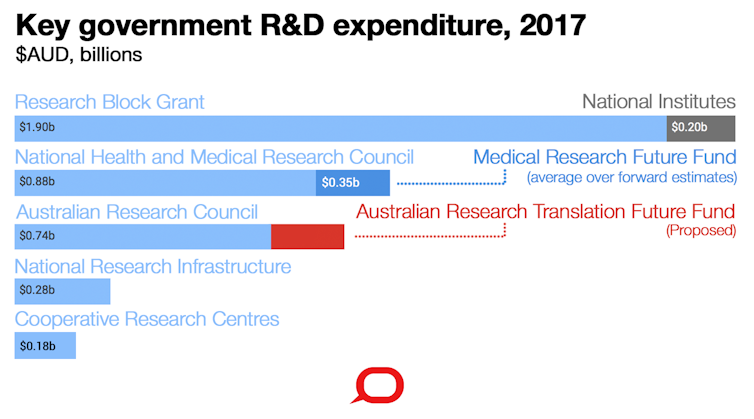

The first is to create a separate fund to support the translation of non-medical research. (The translation of medical research is already supported via the Medical Research Future Fund.) The second is to reform the tax incentives for business and enterprise research and development to better reward industry-university collaboration in the translation of research.

UNSW President and Vice-Chancellor Professor Ian Jacobs. Photo: Grant Turner/Mediakoo

Commercialising an idea, innovation or great piece of research is a key driver of new sources of revenue, jobs and industries, and the lifeblood of increasingly knowledge-intensive economies.

But it is not an easy process. For an idea to make the successful journey from discovery to commercialisation, basic research must be tested through prototypes and trials. If we want this to happen, we need funding that specifically targets the research translation process.

We should create an Australian Research Translation Future Fund (ARTFF). Its role would be to focus on translation of the research currently funded by the Australian Research Council (ARC). In so doing it would mirror the role played by the Medical Research Future Fund (MRFF) in translating research funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC).

Author provided/The Conversation, CC BY-ND

The importance of funding medical research is beyond question, but there are many challenges facing our society that fall outside the medical category. Advances in science, technology, engineering, humanities, social sciences, arts, design and mathematics are also critical to our prosperity and wellbeing.

Grants for fundamental research and industry linkages in all these areas are administered by the Australian Research Council (ARC) which has funding broadly equivalent to the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC).

But while the NHMRC funding is complemented by the Medical Research Future Fund (MRFF), the ARC has no equivalent. A new translation fund for ARC-funded research could support research in priority areas such as food, soil and water, transport, energy, environmental change and cyber security.

While there is still some debate about the best way to administer the relatively new Medical Research Future Fund, in broad terms it presents a model that could be followed in the creation of a research translation fund for non-medical research.

Established in 2015, the Medical Research Future Fund is an endowment fund that will hit $20 billion upon maturity in 2020-21. It is expected to spend $1.4 billion over the forward estimates to 2021. The average annual spend over this period is shown in the schematic. Beyond 2021, annual expenditure is expected to be some $1 billion.

Ideally, an Australian Research Translation Future Fund would make an annual investment in research translation of similar scale.

My second proposal addresses Treasurer Scott Morrison’s recent call for an overhaul of the research and development tax incentive. It aims to reward R&D undertaken on projects additional to business-as-usual.

The Australian government refunds about $3 billion of the $16.7 billion that business spends on research and development through its R&D tax incentive scheme. Currently, this scheme does nothing to encourage collaboration with publicly-funded research organisations such as universities.

This needs to change. Both the 2016 review of the tax incentive and the the government’s Australia 2030 innovation report recommended a collaboration premium to encourage industry to partner with publicly-funded research institutions.

We should endorse the 2016 review’s recommendation for a collaboration premium up to 20% for the non-refundable R&D tax offset for companies with a turnover of $20 million or more (a rise from 38.5% to 58.5%).

With company tax at 30% this would deliver a net saving as a percentage of eligible R&D expenditure of 28.5%, substantially higher than the current 8.5%. The recommended premium also applies to the cost of employing PhD or equivalent graduates in science, technology, engineering and maths in their first three years of employment.

A collaboration premium would pull industry towards universities. If implemented alongside a proposed cap on the annual cash refund to small to medium enterprises and a threshold R&D percentage, the R&D tax incentive collaboration premium could be largely budget-neutral.

A university push toward collaboration through an ARTFF, and an industry pull through an R&D collaboration premium, would be a powerful combination. It would help us deliver on Education Minister Simon Birmingham’s goal of promoting “good research ideas that can be applied or commercialised to provide real-world measures that benefit all Australians and our economy.”

The current R&D ecosystem has imbalances in the funding of medical and non-medical research, coupled with insufficient engagement between industry and universities. Both are factors in the worrying discrepancy between Australia’s research excellence and our ability to apply and commercialise our ideas.

![]() A tax incentive coupled with a new fund to support research translation could go a long way toward closing that gap.

A tax incentive coupled with a new fund to support research translation could go a long way toward closing that gap.

Professor Ian Jacobs is the President and Vice-Chancellor of UNSW Sydney.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.