Does the KonMari method work for clinical hoarders?

While the KonMari method will help many people declutter their houses and reassess what they really need, for people with clinical hoarding disorder the process is much more complicated.

While the KonMari method will help many people declutter their houses and reassess what they really need, for people with clinical hoarding disorder the process is much more complicated.

Australia is the sixth-largest contributor of household waste per capita in the world. We spend more than $A10.5 billion annually on goods and services that are never or rarely used.

One-quarter of Australians admit to throwing away clothing after just one use, while at the other end of the extreme, 5% of the population save unused items with such tenacity that their homes become dangerously cluttered.

If unnecessary purchases come at such a profound cost, why do we make them?

We acquire some possessions because of their perceived usefulness. We might buy a computer to complete work tasks, or a pressure cooker to make meal preparation easier.

But consumer goods often have a psychological value that outweighs their functional value. This can drive us to acquire and keep things we could do without.

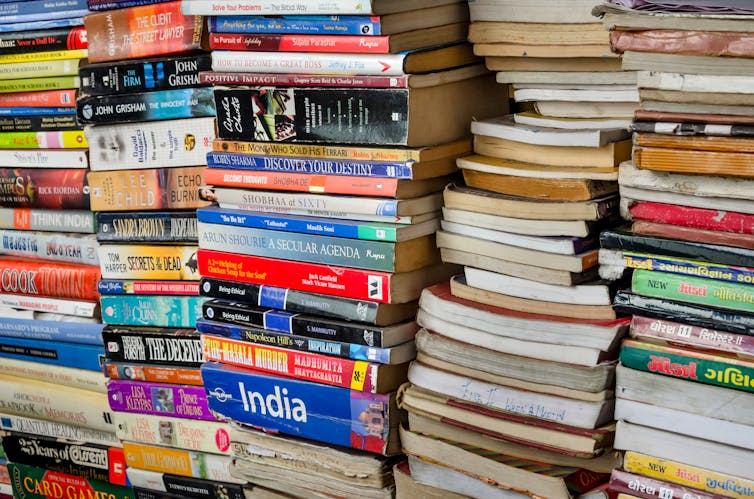

Possessions can act as an extension of ourselves. They may remind us of our personal history, our connection to other people, and who we are or want to be. Wearing a uniform may convince us we are a different person. Keeping family photos may remind us that we are loved. A home library may reveal our appreciation for knowledge and enjoyment of reading.

Family photos show our connection to people we love. Image from istock

Acquiring and holding onto possessions can bring us comfort and emotional security. But these feelings cloud our judgement about how useful the objects are and prompt us to hang onto things we haven’t used in years.

When this behaviour crosses over into hoarding disorder, we may notice:

a persistent difficulty discarding possessions, regardless of their actual value

that this difficulty arises because we feel we need to save the items and/or avoid the distress associated with discarding them

that our home has become so cluttered we cannot use it as intended. We might not be able to sit on our sofa, cook in our kitchen, sleep in our bed, or park our car in the garage

the saving behaviour is impacting our quality of life. We might experience significant family strain or be embarrassed to invite others into our home. Our safety might be at risk, or we may have financial problems. These problems can contribute to workplace difficulties.

According to Japanese tidying consultant Marie Kondo, “everyone who completes the KonMari Method has successfully kept their house in order”.

But while some aspects of the KonMari method are consistent with existing evidence, others may be inadvisable, particularly for those with clinical hoarding problems.

Kondo suggests that before starting her process, people should visualise what they want their home to look like after decluttering. A similar clinical technique is used when treating hoarding disorder. Images of one’s ideal home can act as a powerful amplifier for positive emotions, thereby increasing motivation to discard and organise.

Next, the KonMari Method involves organising by category rather than by location. Tidying should be done in a specific order. People should tackle clothing, books, paper, komono (kitchen, bathroom, garage, and miscellaneous), and then sentimental items.

Organising begins with placing every item within a category on the floor. This suggestion has an evidence base. Our research has shown people tend to discard more possessions when surrounded by clutter as opposed to being in a tidy environment.

However, organising and categorising possessions in any context is challenging for people with hoarding disorder.

People who hoard might have an emotional reaction to all their books. Sharad Raval/Shutterstock.

Marie Kondo gives sage advice about whether to keep possessions we think we’ll use in the future. A focus on future utility is a common thinking trap, as many saved items are never used. She encourages us to think about the true purpose of possessions: wearing the shirt or reading the book. If we aren’t doing those things, we should give the item to someone who will.

Another Kondo suggestion is to thank our possessions before we discard them. This is to recognise that an item has served its purpose. She believes this process will facilitate letting go.

However, by thanking our items we might inadvertently increase their perceived humanness. Anthropomorphising inanimate objects increases the sentimental value and perceived utility of items, which increases object attachment.

People who are dissatisfied with their interpersonal relationships are more prone to anthropomorphism and have more difficulty making decisions. This strategy may be particularly unhelpful for them.

One of Kondo’s key messages is to discard any item that does not “spark joy”.

But for someone with excessive emotional attachment to objects, focusing on one’s emotional reaction may not be helpful. People who hoard things experience intense positive emotions in response to many of their possessions, so this may not help them declutter.

Sustainability Victoria recently urged Netflix-inspired declutterers to reduce, reuse, and recycle rather than just tossing unwanted items into landfill.

Dumping everything into the op-shop or local charity bin is also problematic. Aussie charities are paying A$13 million a year to send unusable donations to landfill.

Ultimately, we need to make more thoughtful decisions about both acquiring and discarding possessions. We need to buy less, buy used, and pass our possessions on to someone else when we have stopped using them for their intended purpose.

Melissa Norberg, Associate Professor in Psychology, Macquarie University and Jessica Grisham, Professor in Psychology, UNSW

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.