A basic income for hard times

The government’s new income support could be strengthened by extending support to migrants, families with children, private tenants, and people on pension payments, says UNSW expert.

The government’s new income support could be strengthened by extending support to migrants, families with children, private tenants, and people on pension payments, says UNSW expert.

In an emergency, governments improvise. Two new systems of income support have been announced in just over a week to keep us going as much of the economy shuts down.

On 30 March, the Government announced a $130 billion wage subsidy scheme to keep people employed. This followed the announcement on 23 March of a $66 billion income support package for people who lose their jobs. That earlier package is the subject of this article.

Its centrepiece was a new payment dubbed a ‘welfare wage’ that draws us into the unfamiliar terrain between our traditional income support system and the unemployment insurance common to other OECD nations.

It doubles the Jobseeker Payment (formerly Newstart Allowance) for single adults to around $560 a week via a new ‘COVID Supplement’, and extends the increase to existing recipients of employment-related and student payments.

There are tensions between these two systems. Income support (pensions and allowances) is designed to meet basic expenses for people in families with few resources. Unemployment insurance compensates individuals for a loss of income from employment, and isn’t as strictly means-tested.

With large parts of the economy shut down by governments to protect our health, both are needed (along with the wage subsidies), and fast. So the new income support package must meet conflicting objectives and be simple to administer. By what magic can we pull this off?

The welfare-wage brings us closer to a ‘Basic Income’ scheme: a minimum income floor that covers essential living costs, extending further up the family income scale than traditional income support.

When it was announced, the welfare-wage (like the Jobseeker Payment) was confined to singles earning up to $27,000 and couples on up to $50,000. A week later it was extended to people whose partners earned up to $80,000.

This is not a ‘Universal’ Basic Income, which extends to everyone and (for that reason) is unlikely to be high enough to cover essential living costs.

An idealised Basic Income would guarantee that different types of families can reach the same minimum living standard unless they face exceptional costs. In addition to the minimum cost of supporting a single adult, it should take account of the largest variable costs: an extra adult or children in a family, and housing costs.

Our traditional income support system fails to do this.

The Jobseeker Payment for single unemployed people is just $282 a week, $190 less than the pension – similar needs, vastly different payments.

Over a million migrants, who are for the most part unable to leave Australia now, are excluded from income support should they lose their jobs. They include many temporary migrants, asylum seekers, and people on bridging visas while their applications for permanent residency are processed.

The maximum rate of Rent Assistance for private tenants on low incomes is $70 a week for a single adult, less than a quarter of rents for a one bedroom flat in our three largest cities.

The first step is to patch these and other gaps in the safety net. The COVID Supplement, which the Government indicates will expire in September 2020, doubles the Jobseeker Payment for singles and extends to each partner in a couple.

This is welcome news to those struggling on Newstart, and will help middle income-earners with higher spending commitments who face a sharp drop in income if they are laid off.

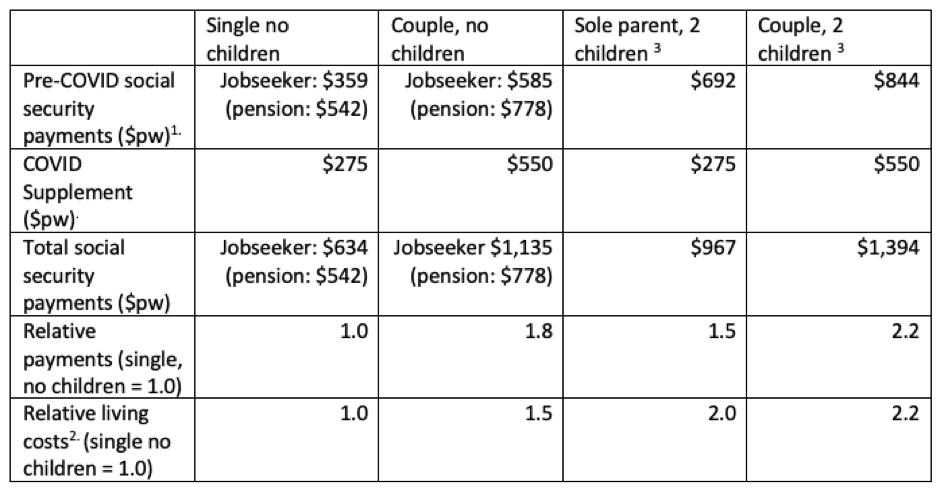

Yet from a Basic Income perspective, the COVID Supplement opens up fresh anomalies. Based on research by Saunders and Bedford on the minimum costs of low-income households, a couple without children needs 1.5 times the income of a single adult to reach the same living standard, a sole parent with two young children needs twice the single rate, and a couple with two children needs 2.2 times the single rate.

The COVID Supplement, when combined with existing social security payments, strongly favours couples without children, who receive 1.8 times the single rate. A sole parent with two children fares relatively poorly at 1.5 times, while a couple with two children receives 2.2 times the single rate. This is due to couples receiving twice the single COVID Supplement instead of 1.5 times (as for pensioner couples), and the absence of a COVID-related allowance for children.

Basic living costs and social security payments for different unemployed families (May 2020)

Sources: Saunders P & Bedford M (2017), New Minimum Income for Healthy Living (MIHL) Budget Standards for Low-Paid and Unemployed Australians, Social Policy Research Centre, UNSW Sydney; Department of Human Services (2020), Guide to government payments, April 2020. 1. Includes Jobseeker Payment, Family Tax Benefit & Energy Supplement & Rent Assistance. (pension rates added for comparison – refers to Age and Disability Pensions and Carer Payment – Rent Assistance & Energy Supplement are also included in these amounts). 2. In 2016. 3. Children are aged 8-11 years.

All things equal, families with children or high rent payments are likely to face greater hardship than others who lose their jobs. Improved child and rental supplements would help (the maximum rate of Family Tax Benefit Part A already extends, in part, to families with two children on up to about $90,000 so an increase in this payment would help many middle-income families).

The COVID Supplement does not apply to pensions. From a social insurance perspective, it might be argued that in contrast to people losing their jobs, their financial situation won’t change much. Yet it’s likely that the cost of essentials will rise and indexation won’t compensate until after the event.

From a pure Basic Income perspective, a single person with a low income would receive the same amount altogether whether on a pension or allowance payment. Similarly, after the emergency, the single Jobseeker payment would be the same as the pension.

In designing its welfare-wage, the government has sensibly ‘started at the bottom’ – those at risk of destitution and those already on Newstart who face it daily. Gaps and anomalies in the new income support ‘floor’ could be solved by extending income support to new and temporary migrants and, at the cost of a bit more complexity, by offering additional support to families with children, private tenants, and people on pension payments based on their relative needs.

An equitable income floor, together with the wage subsidies, could shield most low and middle income households from financial hardship arising from either a lack of income, or a sudden large drop in income.

This should be backed by policies like the JobKeeper Payment that keep as many people as possible employed, and wider economic and employment policies to keep job opportunities open for those already unemployed, and young people unfortunate enough to enter the labour market in these hard and extraordinary times.

Dr Peter Davidson completed his PhD in social policy at the UNSW Social Policy Research Centre and is currently Adjunct Senior Lecturer.

Republished with permission from the Tax and Transfer Policy Institute, ANU.