Retracing the Sydney Meridian: from early colony to contemporary Australia

An exploration of the history of the Sydney Meridian re-imagines Australia’s relationship with territory and time for an artist from UNSW Art & Design.

An exploration of the history of the Sydney Meridian re-imagines Australia’s relationship with territory and time for an artist from UNSW Art & Design.

Artist Lily Hibberd is something of a bower bird, drawn to unique narratives. Her most recent project, Boundless – out of time, is driven by a curiosity around memory and time. Inspired by the Sydney Meridian, the project involved a month-long artist and research residency at Sydney Observatory.

The project was commissioned for NIRIN, the 22nd Biennale of Sydney, and is the culmination of a passion dating back more than a decade. Through the Sydney Meridian, Dr Hibberd interrogates the colonial need to regulate time and claim place, in line with the Biennale’s focus on how past anxieties shape the urgency of the present.

Boundless… maps a virtual walk from the Sydney Observatory to Sydney Town Hall, along the Sydney Meridian. Each day for twenty-four days the adjunct lecturer from UNSW Art & Design visits a “station” along the line, tracing its history and exploring “fictions, assumptions and random observations about the establishment of time and its measure in colonial Australia”.

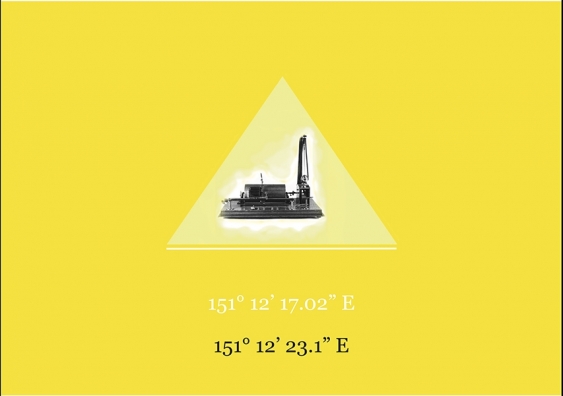

Each station has its own poster with a historical reference to the Meridian and its various coordinates showing that the Meridian is not as fixed as it seems but shifts in keeping with our changing planet.

“Neither time nor territory can be bound by absolute rules,” Dr Hibberd says. “The rift between time and space represented in the Sydney Meridian questions Eurocentric and colonial assumptions, including technological determinism.”

A meridian is “an arc drawn through an imaginary ‘great’ circle that passes through the two celestial poles”, Dr Hibberd explains. Sydney’s Meridian is a north-south line that passes through the Observatory’s transit telescope. It was used to determine time in the early colony, and as one of the tools required to survey and lay claim to the land.

“From the late 16th century, geodesy [a trigonometric survey method that uses the Meridian] went hand-in-hand with a massive imperial expansion that succeeded to map out, measure and use this rationale to claim land beyond the borders that colonisers argued was ‘ownerless’ because it had not yet been charted in this way,” she says.

Through the course of the virtual walk, Dr Hibberd maps out how attempts to measure time have contributed to “a contested history that hinges on the doubtful sovereignty of the British to undertake these claims in the first place”.

The Meridian has shifted over time due to continental drift and the unreliability of the instruments used to measure it, she says. This further destabilises a colonisation based on the false assumption of terra nullius, and questions the sense in holding “the ever-changing conditions of the planet to such orthodox measures” as time and history, she says.

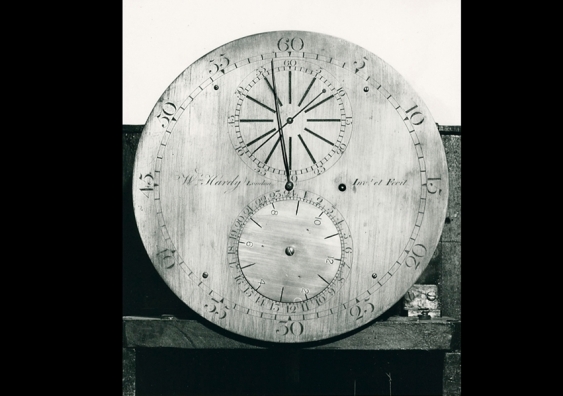

Dr Hibberd has created posters for each station with a historical reference to the Sydney Meridian and the shifting coordinates of the Meridian. Image: Lily Hibberd for Boundless – Remapping Sydney Meridian, 2020, including image of the Melbourne Chronograph, 1870s-1890s, from Museums Victoria collection, public domain

The virtual walk takes Dr Hibberd back and forth across history and the globe, directed by disparate stimuli at each station ranging from the personal to the universal.

For example, a postcard of a vintage chronographic recorder found in the Sydney Observatory sparks a consideration of the affinities between making art and marking time. The chronograph records time by making pinholes on a rolling drum of paper.

For Dr Hibberd, the postcard triggers memories of historical, artistic and personal significance: from an ancient bone carving to an evocative artwork to the pianola in her father’s home.

“It was not the first time I’d thought about time being marked on paper, which seems to be an artistic phenomenon as well as a continuum of the ancient art of marking time,” she says.

“A bone carving from the Upper Palaeolithic era is thought to be one of the earliest objects using a symbolic notation to represent an astronomical cycle. The engravings on the bone carving remind me of an essay I wrote in 2007, to accompany an exhibition of Natalya Hughes’ works in Melbourne – For and From My Father – a tribute to her dying parent.”

Like the drum of the chronograph, Natalya’s works on paper are pierced but “with her grief”.

“They inspired me to write about [the] entwinement of [emotion and its] punctuation with time, specifically recalling a pianola from my own father’s home. As it happens, ‘Blue Moon’ is the only tune I can ever remember it playing.”

This mention of the moon takes her back to the chronograph and the Meridian and the measure of time. It completes the arc from the historical to the artistic to the personal to the universal. Her approach in this way mimics the long arc of the Meridian that bridges polar opposites.

Equally, Boundless… traces the trajectory of Dr Hibberd’s own art practice, mapping her intrigue with how our understanding of time has impacted narratives of identity.

“These contradictions have preoccupied me for quite a few years, inspiring numerous artworks and several trips around the spheroid Earth,” she says.

Her 2009 video installation, First Love, explored the rift between human conceptions of time as linear and the ever-changing nature of time across the cosmos. In 2011, Seeking a Meridian examined French timekeeping devices within their historical context.

A year later, on a hot late summer’s day, she made an impossible attempt to traverse the Paris meridian in a day captured in a photographic essay. And in 2015, with astronomer Suzanne Débarbat, she retraced the history of women who had worked at the Observatory of Paris dating up to World War Two in In the Footsteps of Venus.

For Dr Hibberd, the interplay between the aesthetic and the pragmatic paired with memory creates a pregnant place for reimagining our futures.

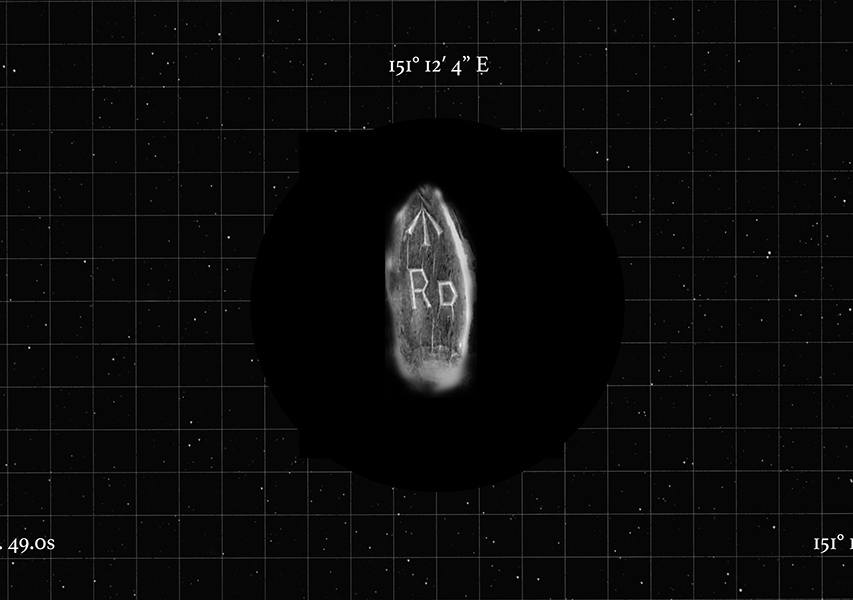

Part of a digital collage showing the changing Sydney Meridian coordinates and the tree scar used in the Australian survey of land, part of Boundless – Remapping Sydney Meridian, 2020, 31 x 16 cm. Astrographic glass plate image reproduced courtesy of Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences and NSW State Archives. Image: Lily Hibberd

This year’s Biennale demonstrates the power of artists and creatives to resolve, heal, dissect and re-imagine transformative futures. Presented by Powerhouse Museum as part of NIRIN and supported by Australia Council project funding, in Boundless… Dr Hibberd challenges contemporary Australia to reconsider our relationship with the land through her exploration of the Sydney Meridian’s history.

She questions the sense of imposing linear thinking on a non-linear world and reveals the contradiction inherent in the empirical premise that all of nature can be claimed and controlled. For Dr Hibberd the potential for our transformative future lies in our embracing our First Nations.

“It is hard for those of us born under this universal system to imagine a different kind of time, one spans the life of the universe – although this premise is not foreign to thinkers of a certain ilk, nor for First Nations cultures in tune with the cosmos,” she says.

“These questions have become part of recent discourse regarding the époque in which humans came to dominate the planet with irrevocable consequences for life on Earth.”

Dr Hibberd leaves her walk with the Uluru Statement from the Heart, and as such it is her chosen destination with its references to ‘time immemorial’ that exists beyond the linear and sovereignty of the land based on a spiritual connection.

Dr Hibberd is a UNSW Sydney Adjunct Lecturer and was an ARC Fellow in the National Institute of Experimental Arts (NIEA) from 2016 to 2019. She has exhibited internationally in major museums, festivals and as the result of extended residency based and collaborative commissions for over 20 years.