How the study of dolphin airways could help save endangered whales

A UNSW study shows airway bacteria can indicate the health of dolphins and whales – a finding that could benefit endangered species like the northern right and blue whales.

A UNSW study shows airway bacteria can indicate the health of dolphins and whales – a finding that could benefit endangered species like the northern right and blue whales.

Diane Nazaroff

0424479199

diane.nazaroff@unsw.edu.au

A UNSW researcher has found promising evidence that airway samples can help assess the health of dolphins and whales, a development which could help save endangered groups of the sea mammals.

An eight-month study of 13 bottlenose dolphins at Sea World on the Gold Coast led by UNSW Science researcher Dr Catharina Vendl analysed samples from the airways of both sick and healthy animals.

It provides the first long-term evidence that dolphins have their own individual ‘signature’ bacteria in their airways.

“This discovery means that there is a good chance that these bacteria are indicative of the dolphins’ health, as the bacteria interact with the host’s immune system, like bacteria do in the gut,” Dr Vendl said.

“Dolphins and whales are closely related. Whales harbour bacteria in their airways in a similar way to dolphins. Therefore, I suggest that the health of whales can be assessed by testing the whales’ airway bacteria.”

Dr Catharina Vendl. Photo: Supplied.

Dr Vendl said the aim behind her research was to find out if the airway bacteria can be used as biomarkers for the health of dolphins and whales.

“This area of research is still relatively new and essential knowledge about the airway bacteria of cetaceans is lacking,” she said.

“This is because it is virtually impossible to take a blood sample from a whale in the wild to assess its health status.

“Sure, we know that every mammal has gut bacteria that interact with its host, such as in its immune function and digestion.

“Those bacteria are specific to the individual, but also specific to the species.

“However, for the bacteria in the cetaceans’ airways, we still know very little about how host and species-specific they are.”

Until now, researchers have also lacked crucial knowledge on the long-term stability of the airway microbiota and its potential changes when the whales and dolphins are sick.

“We would have liked to take blow samples of the same whales over several months, but this is not possible, because the whales migrate and we can’t follow them all the way up and down the coast to continuously take samples from them,” Dr Vendl said.

She said the Sea World dolphins’ controlled living conditions provided a lot of extra information that they couldn’t get from wild dolphins or whales.

“For instance, we knew their age, their sex and the dolphin trainers also reported if they were sick or healthy,” she said.

“So it was much easier to correlate the data of the airway microbiota with other parameters of the dolphins. We found for example that there was a difference between the bacteria of the females and the males. We would not have been able to see such things in whales we have studied, as we were not able to determine their sex.”

The study also showed there were differences in the airway microbiota between the different age groups of dolphins, and between each pool where the dolphins were kept.

“The dolphins within each group 'inoculated' each others' airways with their bacteria, which were basically shared around as dolphins usually don’t maintain social distance to each other,” Dr Vendl said.

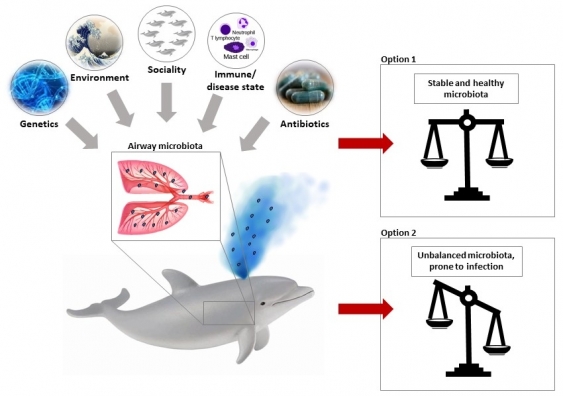

Several factors affect the composition of airway bacteria in dolphins which can result in a healthy or sick dolphin. Graphic: supplied

There was also evidence that four dolphins which received antibiotics for illness had suffered from slightly changed microbial communities.

“The main study finding is that the dolphins maintained an average of the same 73% of blow bacteria over the entire sampling period. In addition, the bacteria were not only specific to each individual dolphin but also to dolphins as a species. This shows that the bacteria in the airways of dolphins inhabit the airways long term, which means we can use it as a health assessment tool.”

Dr Vendl’s latest study, published in BMC Microbiology, mimics previous respiratory studies on mice and humans which showed that respiratory disease is accompanied by a shift in microbial communities of the airways.

The study followed analysis by Dr Vendl, published in Scientific Reports last year, of samples of whale blow – similar to mucus from a human nose – which she collected off the East Coast of Australia using petri dishes connected to telescopic poles and drones.

That study found “significantly less” microbial diversity and richness on the return leg of the whales’ migration, indicating the whales were likely in poorer health than when their journey began.

“Most people are familiar with the yearly whale migrations and lots of people also see dolphins when they’re out surfing,” Dr Vendl said.

“The thing is that we don’t know anything about them; we don’t know if the population is healthy or not.”

The overarching aim of her research was to develop a non-invasive tool to assess the health of whales and dolphins and mostly in the wild.

“The analysis of airway bacteria has been praised by scientists as a promising tool to assess the health status of otherwise inaccessible whale populations in the wild in a gentle and non-invasive way,” Dr Vendl said.

“But there is still more research to do before it can be used.”

She said this latest discovery could help protect endangered cetaceans such as the northern right and blue whales.

“In order to put efficient conservation management strategies in place, it is crucial to know what the underlying issues of a whale population is,” Dr Vendl said.

“For instance, a whale population could be doing poorly because it has trouble reproducing so that the population can’t recover.

“Or the remaining whales in a population might suffer from poor health due to human stressors or pollution in the oceans.

“We can only address these issues properly, if we have an idea about the health status of the whale population.”

But she says there is still more research to do before this health assessment tool can be used on dolphins and whales in the wild.

“The next steps would be to examine a larger number of dolphins and whales for their blow microbiota; to collect even more additional health parameters (such as body condition score and blood samples in captive dolphins); and to correlate them with the airway bacteria,” Dr Vendl said.

“This is essential to 'calibrate' our new health assessment tool.”

Read the study in BMC Microbiology.