Scientists show how to attack the 'fortress' surrounding pancreatic cancer tumours

Tackling the scar tissue that shields pancreatic tumours from effective drug access is a promising advance in a notoriously hard-to-treat cancer.

Tackling the scar tissue that shields pancreatic tumours from effective drug access is a promising advance in a notoriously hard-to-treat cancer.

Isabelle Dubach

Media and Content Manager

+61 432 307 244

i.dubach@unsw.edu.au

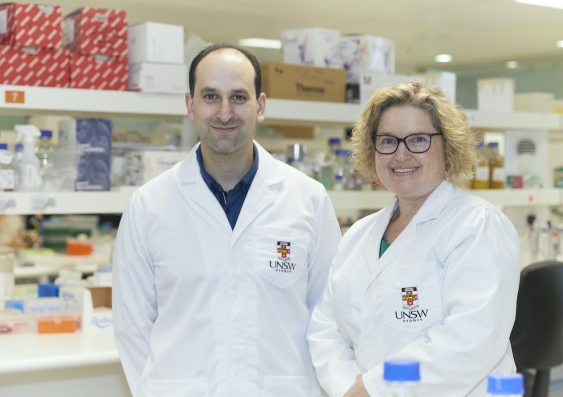

UNSW medical researchers have found a way to starve pancreatic cancer cells and ‘disable’ the cells that block treatment from working effectively. Their findings in mice and human lab models – which have been 10 years in the making and are about to be put to the test in a human clinical trial – are published today in Cancer Research, a journal of the American Association for Cancer Research.

“Pancreatic cancer has seen minimal improvement in survival for the last four decades – and without immediate action, it is predicted to be the world’s second biggest cancer killer by 2025,” says senior author Associate Professor Phoebe Phillips from UNSW Medicine & Health.

“But our latest advance means today I am the most optimistic and hopeful I have been in my career.”

Pancreatic cancer is notoriously difficult to treat because of the dense scar tissue surrounding tumours – the tissue acts like a fortress that blocks chemotherapy delivery.

“This scar tissue is produced by critical ‘helper cells’ – also called cancer-associated fibroblasts – which cancer cells recruit to support their growth and spread. Yet, these helper cells have been ignored in current treatment strategies,” A/Prof. Phillips says.

“Our approach hits both the tumour cells and the helper cells, so it’s ideal for overcoming the aggressiveness and drug resistance of the disease.”

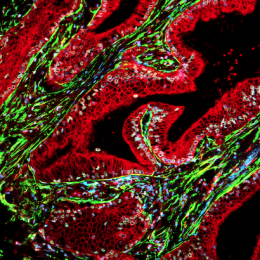

In today’s paper, the team demonstrates their novel way to metabolically rewire helper cells by targeting one particular protein called SLC7A11, which in turn shuts off the cells’ tumour-promoting activity and reduces the scar tissue they produce.

“We found that switching off SLC7A11 in mice with pancreatic tumours directly killed pancreatic cancer cells, reduced the spread of tumour cells throughout their body and decreased the scar tissue fortress,” says Dr George Sharbeen, a postdoc researcher in A/Prof. Phillips’ lab who led the experimental work.

A human pancreatic tumour section showing SLC7A11 in helper cells (yellow). Image: UNSW Sydney

SLC7A11 has been studied in pancreatic cancer cells before, but this is the first piece of research to show that it plays a critical role in non-tumour helper cells, too.

“In other words, we have identified a novel ‘dual cell’ therapeutic target – tackling both the tumour cells and their helpers – which overcomes the current limitations of standard chemotherapy.”

The team used several complementary models to improve the clinical translatability of their findings, including patient-derived pancreatic cancer cell lines and helper cells, 3D at-the-bench models including an explant model that maintains pieces of human pancreatic tumour tissue, and multiple mouse models of pancreatic cancer.

“We also used our cutting-edge nanomedicine we developed in a multi-disciplinary collaboration with engineers – UNSW Professor Cyrille Boyer and University of Queensland Professor Thomas Davis – to deliver a gene therapy to inhibit SLC7A11. This therapy is advantageous because our nano-drug is tiny and able to penetrate the scar tissue in pancreatic cancer,” co-first author Associate Professor Joshua McCarroll from the Children’s Cancer Institute says.

The team’s findings have formed the foundation for a clinical trial led by A/Prof. Phillips and UNSW Medicine collaborator Professor David Goldstein, which was funded by a recently awarded Cancer Institute NSW Translational Program Grant.

“In this trial, we will repurpose an anti-arthritis drug called sulfasalazine – which we know potently inhibits SLC7A11 – for the treatment of pancreatic cancer patients with tumours that have high SLC7A11 levels, which we’ve shown to be the case in more than half of patients. It has the potential to improve treatment response and ultimately survival of these patients,” A/Prof. Phillips says.

The researchers say the opportunity to repurpose an existing drug that’s already in the clinic will help them make progress more quickly.

“Using an approved drug has allowed us to get this piece into the clinic much faster than what would be the case if we started from scratch with drug development, too,” says A/Prof. Phillips.

“We are taking this exciting development all the way from the lab bench through to the clinic with the sole purpose of improving outcomes for patients with pancreatic cancer.”

The research team hopes to analyse and publish the first set of results of the trial within three years.

In addition to the clinical trial, the team now hopes to assess how their approach interferes with the exchange of nutrients between tumour cells and helper cells. They also want to identify the ideal drugs to combine with their therapeutic approach to enhance anti-tumour effects.

Pancreatic cancer is a highly lethal disease, with only one in 10 patients surviving beyond five years. In 2020, an estimated 4000 Australians were diagnosed with pancreatic cancer – about 90 per cent of them will die, often within a few months of diagnosis.

“We clearly need improved treatments to turn these dismal statistics around, and we hope clinical translation of our findings will ultimately increase the number of pancreatic cancer survivors,” says A/Prof. Phillips.

“We will not give up until we improve the quality of life of patients and provide them with an effective treatment.”

This work was funded NHMRC, Cancer Institute NSW and PanKind (The Australian Pancreatic Cancer Foundation).