The site offers details of a verdant landscape 15 million years ago, including fossils of trapdoor spiders, giant cicadas and wasps.

A team of Australian and international scientists led by Australian Museum (AM) and UNSW Sydney palaeontologist Dr Matthew McCurry and Dr Michael Frese of the University of Canberra have discovered and investigated an important new fossil site in New South Wales. The site – named McGraths Flat – contains superb examples of fossilised animals and plants from the Miocene epoch. The team’s findings were published today in Science Advances.

The new fossil site is located in the Central Tablelands, NSW near the town of Gulgong, and represents one of only a handful of fossil sites in Australia that can be classified as a ‘Lagerstätte’– a site that contains fossils of exceptional quality.

Over the last three years a team of researchers has been secretly excavating the site, discovering thousands of specimens including rainforest plants, insects, spiders, fish and a bird feather.

UNSW Senior Lecturer Dr McCurry said the fossils formed between 11 and 16 million years ago and are important for understanding the history of the Australian continent.

“The fossils we have found prove that the area was once a temperate, mesic rainforest and that life was rich and abundant here in the Central Tablelands,” Dr McCurry said.

“Many of the fossils that we are finding are new to science and include trapdoor spiders, giant cicadas, wasps and a variety of fish.

“Until now it has been difficult to tell what these ancient ecosystems were like, but the level of preservation at this new fossil site means that even small fragile organisms like insects turned into well-preserved fossils.”

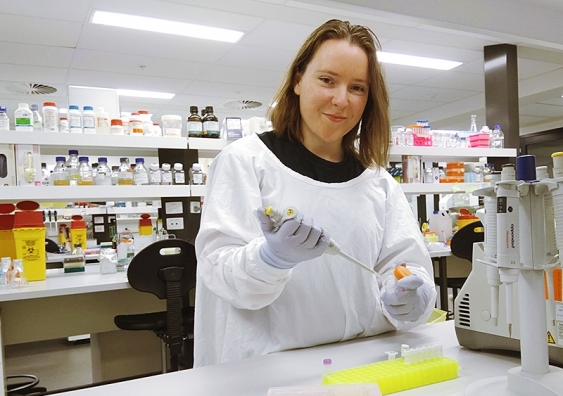

Associate Professor Michael Frese, who imaged the fossils using stacking microphotography and a scanning electron microscope (SEM), said that the fossils from McGraths Flat show an incredibly detailed preservation.

“Using electron microscopy, I can image individual cells of plants and animals and sometimes even very small subcellular structures,” Dr Frese said.

“The fossils also preserve evidence of interactions between species. For instance, we have fish stomach contents preserved in the fish, meaning that we can figure out what they were eating. We have also found examples of pollen preserved on the bodies of insects so we can tell which species were pollinating which plants.

“The discovery of melanosomes – subcellular organelles that store the melanin pigment – allows us to reconstruct the colour pattern of birds and fishes that once lived at McGraths Flat. Interestingly, the colour itself is not preserved, but by comparing the size, shape and stacking pattern of the melanosomes in our fossils with melanosomes in extant specimens, we can often reconstruct colour and/or colour patterns.”

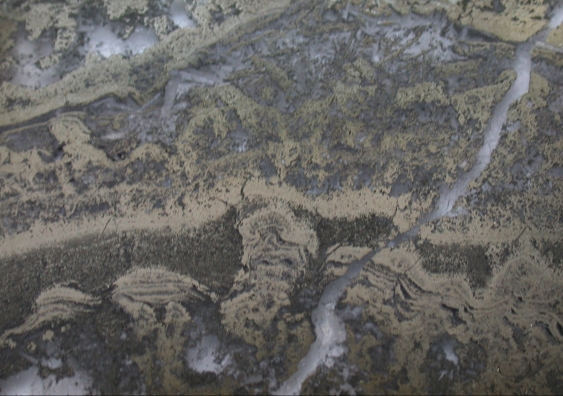

The fossils were found within an iron-rich rock called ‘goethite’, not usually thought of as a source of exceptional fossils. “We think that the process that turned these organisms into fossils is key to why they are so well preserved. Our analyses suggest that the fossils formed when iron-rich groundwaters drained into a billabong, and that a precipitation of iron minerals encased organisms that were living in or fell into the water,” Dr McCurry said.

Dr McCurry said the fossilised plants and animals were similar to those found in rainforests of northern Australia, but that there were signs that the ecosystem at McGraths Flat was beginning to dry.

“The pollen we found in the sediment suggests that there might have been drier habitats surrounding the wetter rainforest, indicating a change to drier conditions,” he said.

Australian Museum Chief Scientist and director of the AM’s Research Institute, Professor Kristofer Helgen, said the fossil site brought to life a picture of outback Australia that we can now barely believe existed.

“Australia is the most unique continent biologically, and this site is extremely valuable in what it tells us about the evolutionary history of this part of the world. It provides further evidence of changing climates and helps fill the gaps in our knowledge of that time and region,” Prof. Helgen said.

“The AM has a rich history of expeditions and scientific research, and we love that the public is always fascinated by these fundamental human endeavours of exploration and discovery.”

Field work at McGraths Flat was funded through the generous donation from a descendant of Robert Etheridge, an English palaeontologist who came to Australia in 1866. Etheridge joined the Australian Museum in 1887 as Assistant Palaeontologist and in 1895 was made Curator of the Museum.

McGraths Flat

First found in 2017, McGraths Flat is named after Nigel McGrath who discovered the first fossils from the site. The site is located near Gulgong in central NSW (Gulgong is a Wiradjuri word that means “deep waterhole”).

The Miocene Epoch (~23–5 million years ago) was a time of immense change in Australia. The Australian continent had separated from Antarctica and South America and was drifting northwards. When the Miocene began there was enormous richness and variety of plant and animal life in Australia. But at around 14 million years ago an abrupt change in climate known as the “Middle Miocene Disruption” caused widespread extinctions. Throughout the latter half of the Miocene, Australia gradually became more and more arid, and rainforests turned into the dry shrublands and deserts that now characterise the landscape. The newly discovered fossil site, McGraths Flat, provides an unprecedented look into what Australian ecosystems were like prior to this aridification.

Media enquiries

Claire Vince

Australian Museum

Tel: 0468 726 910

Isabelle Dubach

Media and Content Manager

Tel: +61 432 307 244

Related stories

-

Scientists estimate the weight of two giant extinct amphibians

-

Ancient marsupial 'junk DNA' might be useful after all, scientists say

-

What lies beneath: lake sediments show link between climate change and bushfires in Aussie Alps

-

Earliest signs of life: scientists find microbial remains in ancient rocks