Need to renew your passport? The weird history of Australian passports explains how they got so expensive

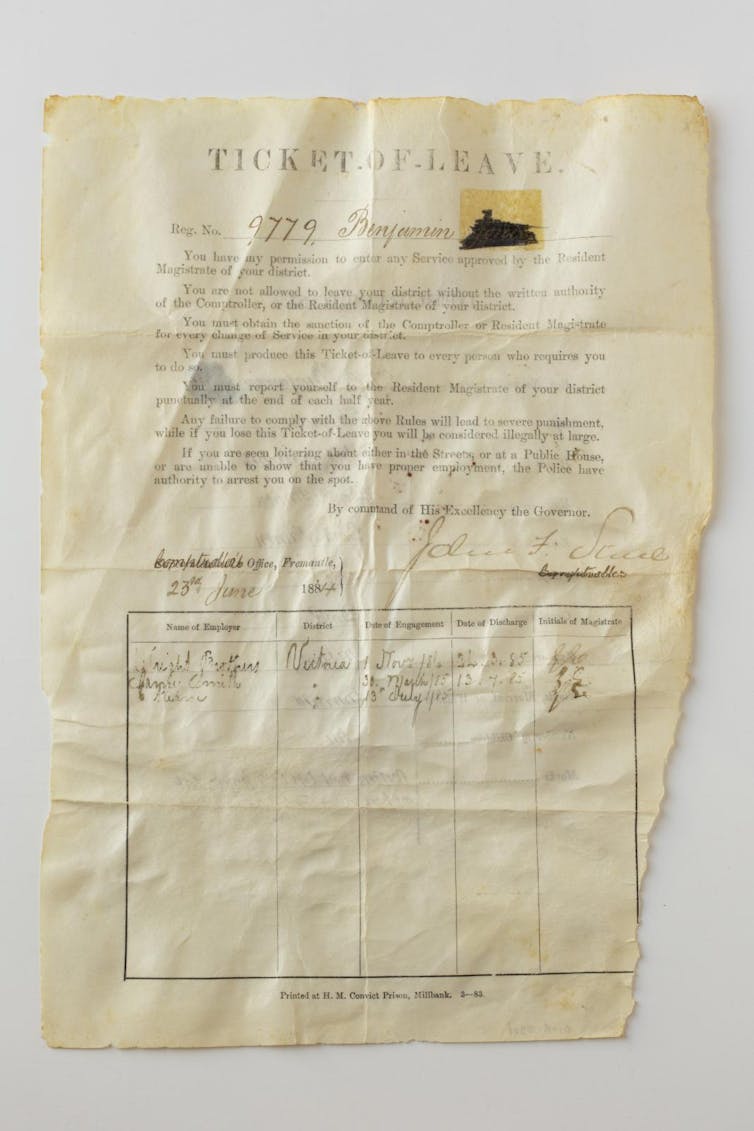

The cost of the Australian biometric passport and the rigour involved in obtaining one can be traced to our participation in an international passport system that evolved over the last century.