Bigotry shows Iran’s true face

If Tehran lies about its treatment of Baha’is, who can trust it on its nuclear agreement, writes Fariborz Moshirian.

If Tehran lies about its treatment of Baha’is, who can trust it on its nuclear agreement, writes Fariborz Moshirian.

OPINION: Just as the Iranian government awaits relief from economic sanctions via last month’s nuclear agreement, it has been exposed as wielding a heinous economic weapon against its biggest non-Muslim religious minority.

In a calculated attack on the beleaguered 300,000 members of the Baha’i faith, the authorities have been closing Baha’i businesses. This breach of internationally accepted economic and human rights comes two years after President Hassan Rouhani promised to improve the climate for religious minorities in his country.

This month, the independent, bipartisan US Commission on International Religious Freedom released a statement saying the situation of Iranian religious minorities remains dire. It described the shop closures as “further impoverishing this marginalised and persecuted community”.

It long has been acknowledged that the situation of the Baha’is, who the clerical authorities revile for following a religion subsequent to Islam, is a litmus test for the human rights situation in Iran. Successive Australian foreign ministers, and the federal parliament itself, have called on Iran to halt the systematic persecution of a community well known to be law-abiding and non-political, and an advocate of peace, harmony and the equality of women and men.

The faith came to Australia in 1920, and Baha’is here come from a wide array of national and ethnic backgrounds. Among them are many with relatives in Iran. They are watching the latest events with apprehension. The use of the economic weapon has a decades-long history but now it is being ramped up to even more heartless levels.

Following the 1979 Islamic revolution, more than 10,000 Baha’is were dismissed from employment in government and universities and effectively excluded from the public and education sectors. Only the private sector was open to them.

The authorities began pressuring private sector businesses that employed Baha’is to dismiss them on the basis of their faith alone.

About a decade ago, the Iranian government began systematically to collect information on the businesses conducted by Baha’is. The Association of Chambers of Commerce began compiling details in relation to the trades and employment of Baha’is and the Ministry of Commerce was instructed to assemble similar statistical data.

In a sinister outcome, individuals recognised as Baha’i are now often subjected to denial of business licences and there are persistent official efforts to severely restrict any further attempts by them to gain employment. Last year the Public Places Supervision Office informed Baha’i shopkeepers in Golestan that their business licences would not be renewed on expiration.

Authorities occasionally have attempted to justify refusal of business licences on the grounds of market saturation, but that is clearly not the reason because the refusals are applied selectively to Baha’is.

Then came the closures referred to in this month’s USCIRF report. In October last year, the authorities sealed 80 Baha’i stores in Kerman. And in April and May this year, dozens of Baha’i small businesses were sealed by Iranian authorities when, in observance of their religious practice, the shopkeepers closed to observe Baha’i holy days.

Some shopkeepers in Hamadan, Kerman and Rafsanjan were threatened with revocation of their business licences should they continue to close their stores for the purpose of observing anything other than nationally recognised holidays, despite the fact there is no law requiring them to do so.

Given the restrictions Baha’is face in obtaining employment in other sectors, the continuation of small businesses is critical to livelihoods and these instances of discrimination reflect a serious and direct threat to the economic subsistence of Baha’is.

Moves to strangle the community economically need to be set in the context of many other aspects of the program of persecution.

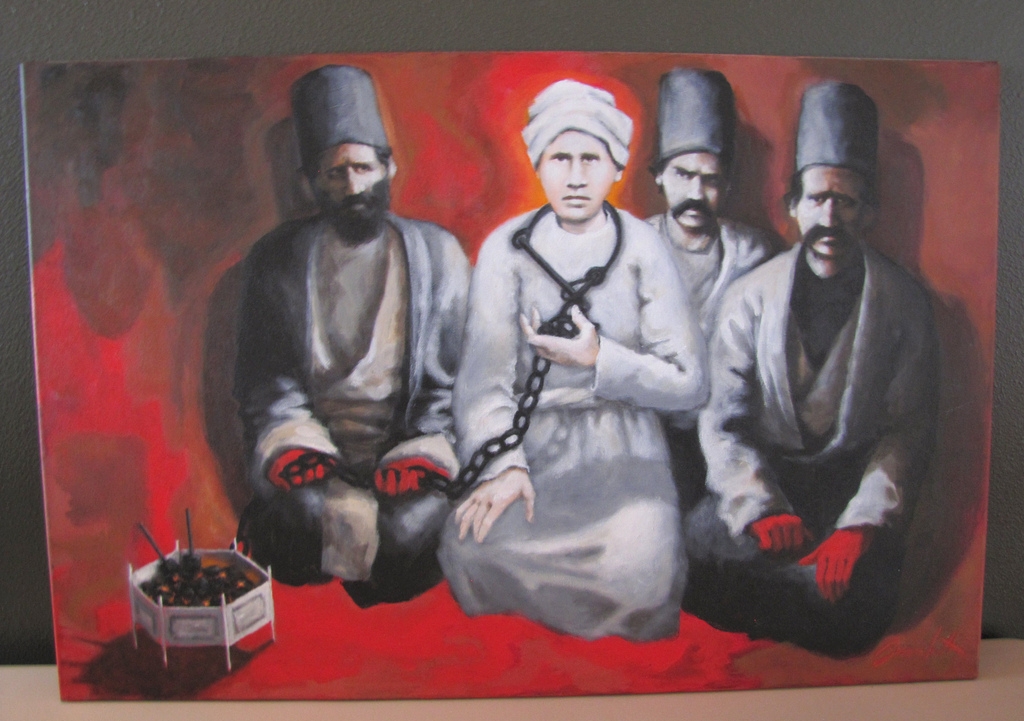

This year marks the seventh anniversary of the wrongful arrest of seven former Iranian Baha’i leaders who were handed sentences of 20 years’ imprisonment after an unfair trial widely condemned by the international community.

Baha’i cemeteries in Tehran, Marvdasht, Semnan and Ghaemshahr have been desecrated or made inaccessible. Official Iranian media is used by the government to demonise and incite hatred of Baha’is, with violent results. Persecution permeates the education system. Baha’i students are denied entry to universities.

In essence, actions by the Iranian government bear striking resemblance to practices of cultural cleansing, and are clearly indicative of aims to drive the 300,000 Iranian Baha’is from their homeland.

The economic pressures are another limb of this campaign.

These combined actions represent a longstanding and systematic government-driven attempt to persecute Baha’is, showcasing Iran’s failure to uphold international human rights norms, including the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, to which it is a party.

The latest economic tactics point to the facade Iran has presented to the international community in maintaining the fiction that Baha’is have full citizenship rights.

As Iran looks forward to the lifting of economic sanctions, there is a way it could prove itself trustworthy to observe agreements.

That would be for the government to call a halt to the persecution of this innocent minority community and to uphold its promise to respect the human rights of all

Fariborz Moshirian is Director of the Institute of Global Finance and Professor of Finance, UNSW Business School.

This opinion piece was first published in The Australian.