We should be told how our High Court judges are chosen

US Supreme Court appointments are infected with the bitter partisanship that pervades US politics while Australian Chief Justice Robert French's impending departure has excited barely a murmur.

US Supreme Court appointments are infected with the bitter partisanship that pervades US politics while Australian Chief Justice Robert French's impending departure has excited barely a murmur.

OPINION: Judicial appointments in the US and Australia tell a very different story. The death of Antonin Scalia, a leading conservative Justice of the US Supreme Court, attracted worldwide attention. Selecting his replacement has also provoked fierce debate among presidential contenders. Nominating someone to join the court is one of the most important powers enjoyed by a US president. A judge can serve on the court for decades, with Scalia chosen in 1986 by Ronald Reagan.

Unfortunately, US Supreme Court appointments are infected with the bitter partisanship that pervades US politics. Every selection is now seen as an opportunity to advance a Democrat or Republican agenda, especially in regard to issues such as abortion. The debate has reached fever pitch, with some on the extreme right even suggesting that Scalia might have been murdered to give Barak Obama a final opportunity to stack the court.

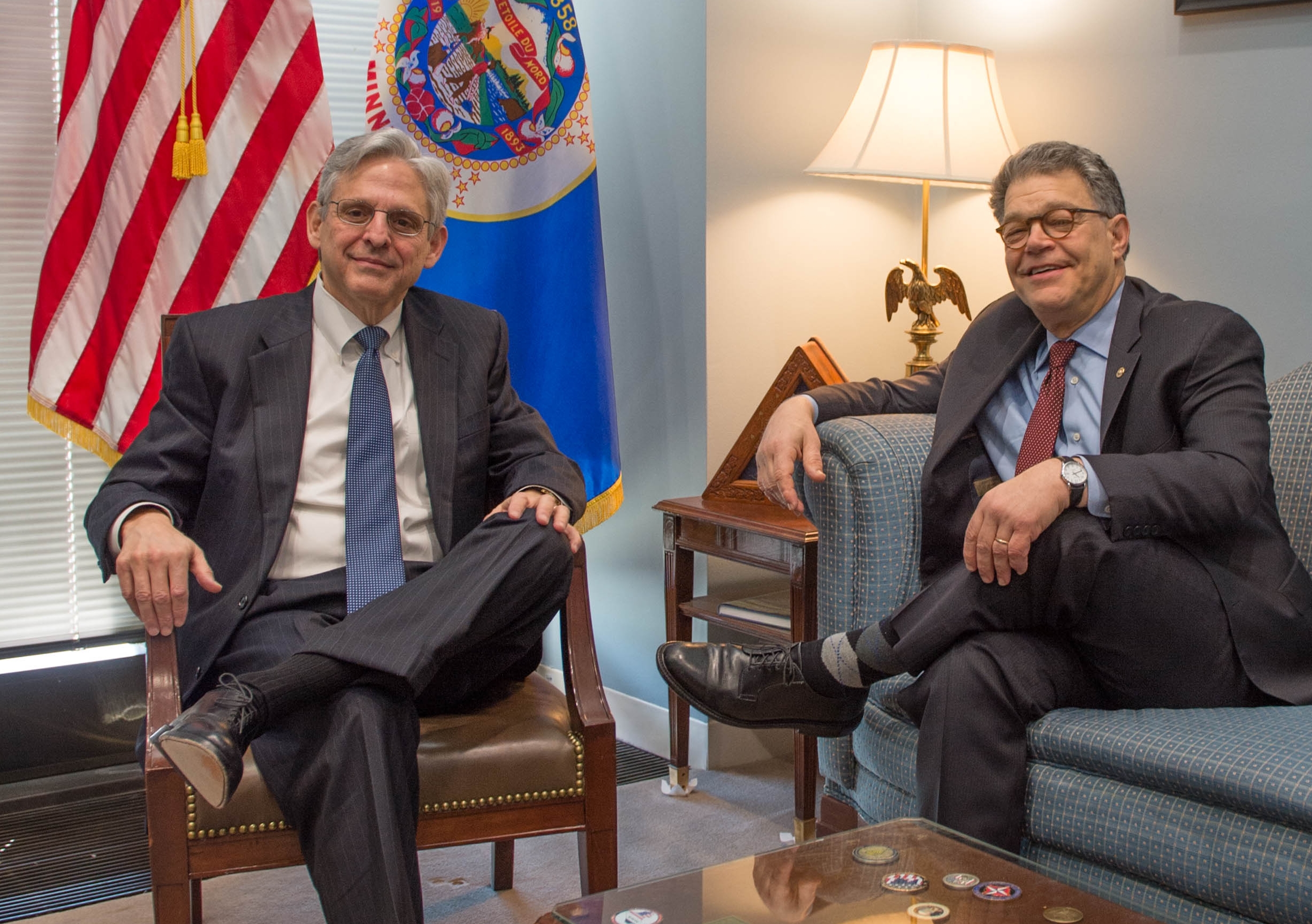

The process of appointing Scalia's successor is at an impasse. Obama has nominated the Chief Judge of the DC Circuit Court, Merrick Garland. Democrats and Republicans recognise his suitability for the office. However, Republicans form a majority in the Senate, and say that they will not confirm any Obama candidate. They hope that the nomination can instead be made in 2017 by a Republican president. In the meantime, the court will be left with an even number of justices, and will be paralysed in the event of a 4:4 split.

The High Court has played a key role in Australian society and politics during Robert French's time as Chief Justice. Photo: Karleen Minney

Australia also faces change on its highest court, but the situation could not be more different. In a low-key statement, Chief Justice Robert French of the High Court has indicated that he will retire on January 29, 2017, a few weeks before he reaches the mandatory retirement age of 70. He is leaving early so that his replacement can join the court at the start of the 2017 sittings.

The High Court has played a key role in Australian society and politics during French's time as Chief Justice. It struck down the Gillard government's Malaysian solution, the ACT same-sex marriage law and parts of the NSW political donation scheme. The court also forged adventurous new understandings of the law in areas such as the federal spending power and the rule of law as it applies to state decision-makers.

French will leave a formidable legacy that demonstrates the great power exercised by the seven judges of the High Court. Despite this, his impending departure has excited barely a murmur. It may not even feature in the upcoming federal election, despite the victor gaining the power to choose his successor.

There is much to dislike about the politicisation of judicial appointments in the US. On the other hand, Australia has gone too far the other way. Our process of the government selecting High Court justices takes place entirely in secret. The announcement of a new High Court judge is a blip on the media's radar, with the newly appointed judge then assuming the anonymity that typically comes with serving in the nation's highest judicial office.

Governments do little to justify their selection, stating only that the person was "appointed on merit". This obscures rather than explains the reasons for the choice. Judges are certainly chosen with reference to their legal skills, but also with regard to considerations such as personal friendships, the person's state of origin and whether the person may interpret the law to uphold government policies.

Australia should make modest changes to adopt a more open and accountable system of judicial appointment. In other nations, procedures have been adopted to identify a broad pool of talented candidates, and to enable a fair selection to be made between them. It is also expected that governments will explain what they are looking for in a judge, and why their candidate possesses those qualities.

For example, Obama has explained in careful detail what he looks for in a Supreme Court justice. The person must have "an independent mind, rigorous intellect, impeccable credentials, and a record of excellence and integrity". They must recognise "the limits of the judiciary's role" and understand "that a judge's job is to interpret the law, not make the law". Finally, the person must have a background and life experience that suggests they will deliver "just decisions and fair outcomes".

Australia could do with the same sort of conversation. The members of our High Court apply the constitution to strike down laws passed by democratically elected parliaments. They also develop the common law and interpret legislation in a way that affects the lives of everyone in the community. Governments should set out what they see as the qualities needed to properly exercise these powers. We must not politicise the appointment of judges, but nonetheless should change the process to bring about more transparency and accountability.

George Williams is the Anthony Mason Professor of Law at UNSW.

This opinion piece was first published in the Sydney Morning Herald.

Twitter: ProfGWilliams