Is 3D printing the future for building?

Published on the 24 Jun 2016

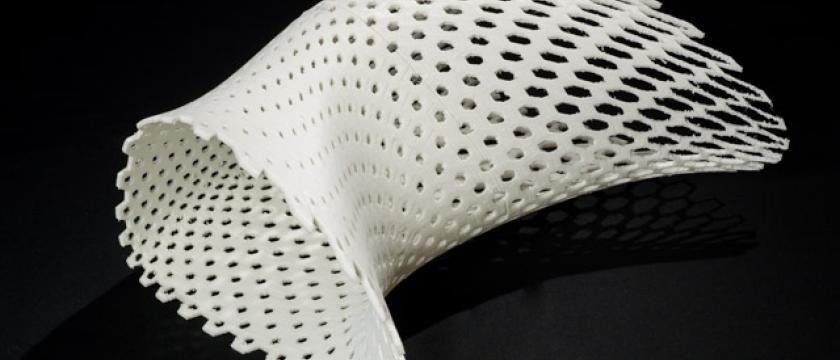

Many companies now look to the technology to produce products cheaper and faster – including the building industry.