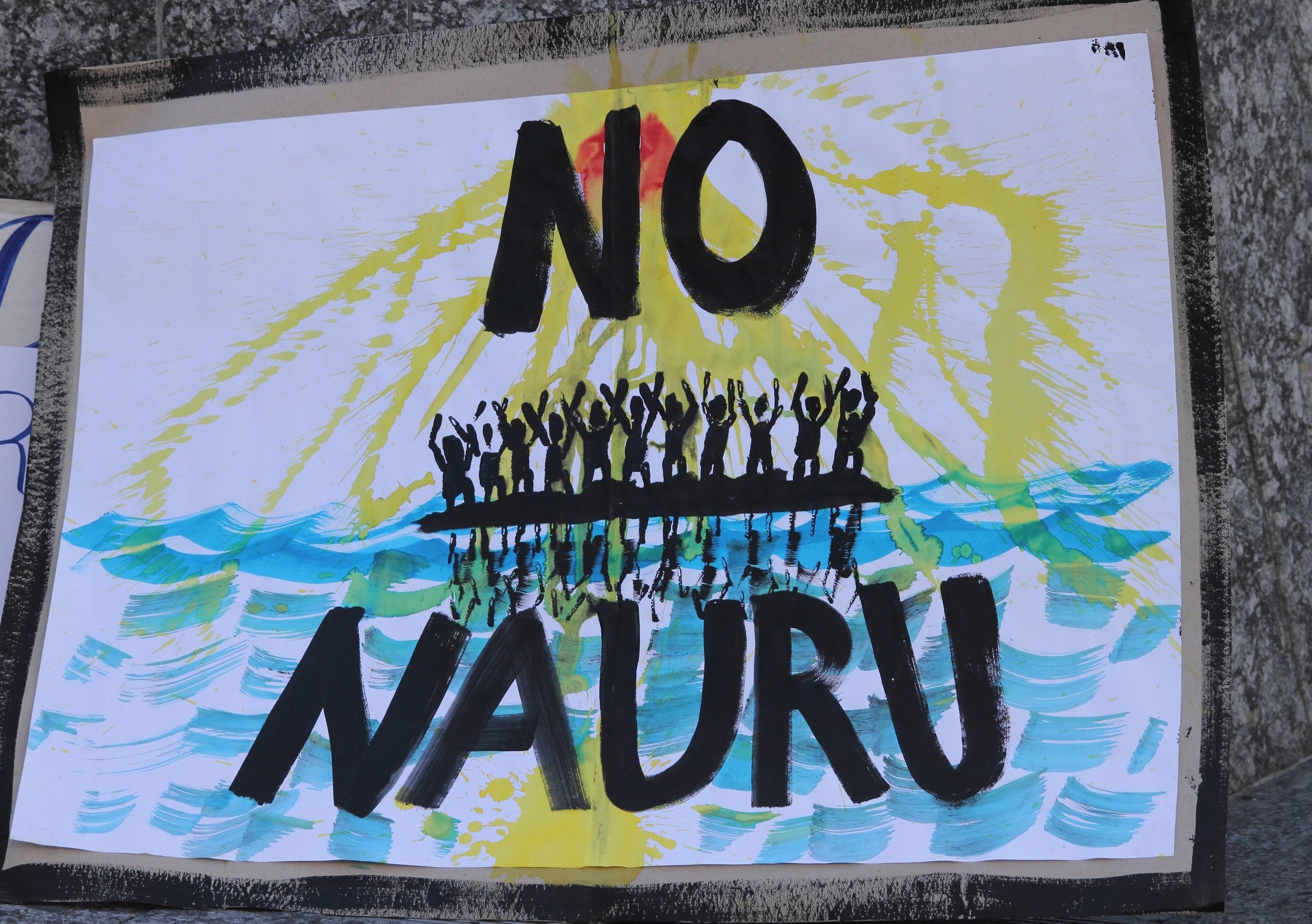

Nauru abuse reports warrant urgent action to protect children in offshore detention

The Australian government must respond to the latest reports of abuse in Australia’s offshore processing centre on Nauru as it did with the children detained at Don Dale, write Madeline Gleeson and Khanh Hoang.