From ‘asylum seekers’ to ‘illegals’. From an Immigration Department to Border Protection officers. From welcoming Indochinese in the 1970s to Operation Sovereign Borders patrols today. Words make worlds, and the human impact of Australia’s shifting language and policy on refugees was vividly laid out for the audience that filled Wotton+Kearney’s 26th floor Sydney office for ‘History, Headlines and the Law: What's shaping refugee policy in Australia?’.

UNSW Law Dean George Williams led the 2 November discussion, which featured alumni and Guardian Australia journalist Ben Doherty, Wotton + Kearney partner Heidi Nash-Smith, and, from UNSW’s Kaldor Centre for International Refugee Law, Acting Director Prof Guy S Goodwin-Gill and historian and Asylum By Boat author Dr Claire Higgins.

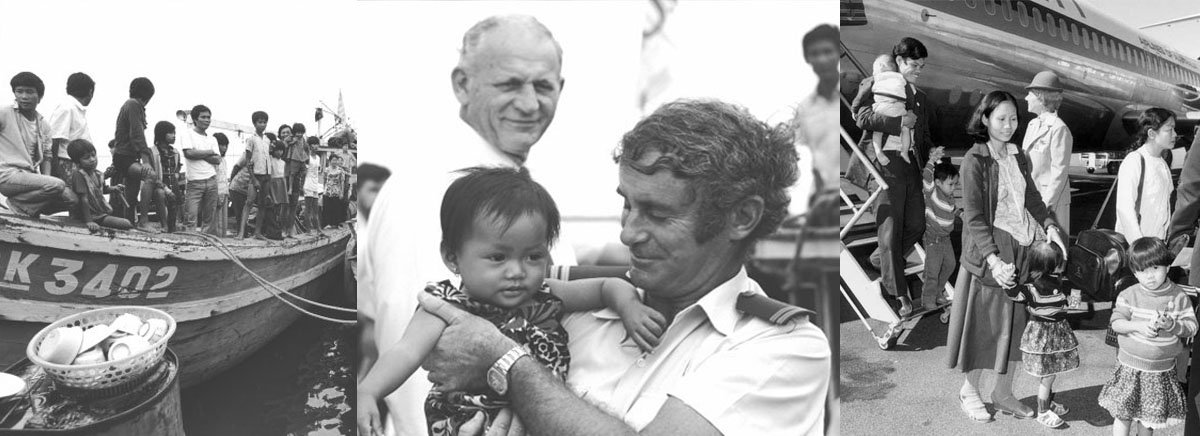

Higgins’ book brings the Fraser years to life, and she described then Immigration Minister Michael MacKellar’s deliberate choice to emphasise the government’s control of the borders by humanising the Vietnamese who were sailing into Darwin. He wanted Australians to know and feel that, as she put it, “everyone settling into your neighbourhood, into your street, deserved protection”.

Goodwin-Gill, who arrived in Sydney in 1978 as the first UNHCR official to be posted in Australia, noted that this was at Canberra’s invitation, “because the government wanted to ensure it was in compliance with its international obligations”.

Since that time, he said, “the discourse has very often been high-jacked by certain sections of the media, and indeed by government itself, which has sought very often to suppress open, well-informed discussion on the causes of refugee movements… the desperation that drives people still to take phenomenal risks, risks that endanger themselves, their families, their children. One has to stop and ask, why do they do that? It’s not simply for a better life. It’s because behind them, there is the desperation of conflict or persecution.”

“We have lost the ability to disagree,” said Doherty, who warned that digging ourselves into metaphorical trenches and hurling invective would simply continue to poison the policy. He noted the challenges of humanising asylum seekers when immigration detention centres were deliberately placed very far from view, and though Doherty himself has been unable to get visas to report on Nauru or Manus, he’s found other ways to enable the asylum seekers and refugees held there to tell their stories.

Some of those have been Heidi Nash-Smith’s clients. Sometimes, she said, they would ask her: “What have I done wrong? Why am I so hated? What does my life hold – will I be released? Will I find a home? Will I be able to study, to build a life for myself? Or is this it? And I don’t have an answer for them, and that is extremely challenging and extremely frustrating.”

Watch the video or listen to the podcast of this fascinating discussion.