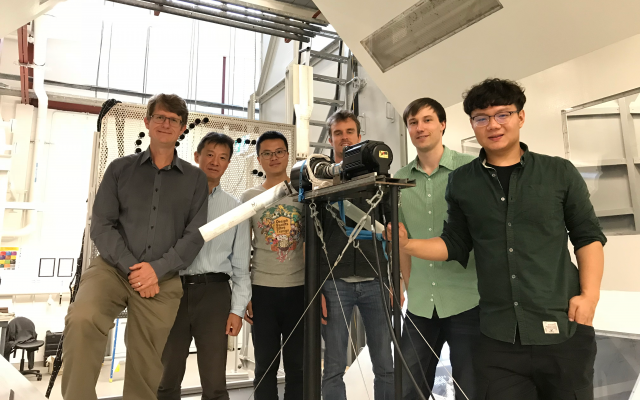

Professor Con Doolan and his aeroacoustics research group from UNSW Mechanical Engineering have just partnered with colleagues at the University of Sydney on a project to create 3D-printed drones for the Department of Defence.

What does this project aim to do?

The drone-on-demand project is about providing the Defence Force with the capability to create specialised, custom-made drones using 3D printing. The idea is that rather than transport a whole series of different drones into the field, all they need to take is a 3D printer and the raw materials. Depending on the specifics of the mission, they put the details into a computer program and the 3D printer creates a drone tailored to that requirement.

What’s your role?

As aeroacoustics engineers, we are interested in the science of sound production by air and water flow. Our role is to distil our expertise into the computer program to make sure the drones are as quiet as possible.

Who are your collaborators and how long has the project been running?

The drone-on-demand project is a 12-month Defence Innovation Network (DIN) funded project that started in October 2018, so we’re just in the early phases at the moment. By the end of the project we aim to provide an algorithm that will link the drone design parameters (i.e. size and shape) to its acoustic signature.

The project was initiated by the University of Sydney who invited us to join them on the application to DIN, which is a relatively new government organisation created to help universities and industry create new technologies for defence.

This research will reduce the acoustic signature of drones, so the Department of Defence can use them undetected. But, more broadly, this technology could be used used on things like submarine propellers, or any underwater vehicle where noise reduction is very important.

Professor Con Doolan, UNSW Mechanical and Manufacturing Engineering

Why do you think the University of Sydney was interested in collaborating with you on this piece of work?

Making a drone quiet is a very important consideration, particularly for the Defence application, and we have a pretty good reputation in this space. We have already been able to demonstrate the use of 3D printing to create quiet rotor blades which would be effective for drones, particularly propellers which are the noisiest thing. We draw our inspiration from different things, but owls are a big one, because certain types of owls can fly very quietly.

Why can owls fly so quietly?

The construction of an owl’s wing is both porous and elastic, so we’ve been trying to create porous structures within the rotor blade that will absorb the sound of the rotor blade itself. We’ve been able to produce and test the material we’ve created in our rotor rig, and have shown it works very effectively.

Is there anything on the market like this at the moment?

Not that I know of. There are lots of drones designed for specific purposes of course, but there is nothing that can create a specific drone for a specific occasion at a specific time.

How could the results of this project make Australia safer?

This research will reduce the acoustic signature of drones, so the Department of Defence can use them undetected. But, more broadly, this technology could be used on things like submarine propellers, or any underwater vehicle where noise reduction is very important.

Are there many civilian applications for this technology?

Yes, lots. Wind turbines are one of our big areas of interest because the noise they create is one of the biggest reasons people don’t want them built in their vicinity. The quieter we can make them, the more wind turbines we can build and the more renewable energy we can generate.

Other applications include cooling fans for computers, air-conditioning systems and high-speed trains. Drone noise reduction is also becoming increasingly important in the civilian sphere. Amazon, for example, are set to start delivering thousands of parcels using drones which could get very noisy and annoying.

What is it that interests you about aeroacoustics?

It combines physics, fluid mechanics and acoustics, which attract my interest academically. But it’s also important to so many technologies. We’re even doing projects on supersonic aircraft, where acoustic loading is really important on their structure.

I don’t think the discipline of aeroacoustics is that well appreciated by the wider public. Our overall objective is to make things quieter for people, to reduce environmental noise and thus improve the quality of life in urban environments, which I think is a pretty inspiring thing to work towards.