The Times Higher Education Research Excellence Summit: Asia Pacific at UNSW Sydney challenged university leaders and researchers to better showcase how they are tackling the world’s major challenges.

More than 200 of the world’s brightest minds converged on UNSW Sydney this week for the 2019 Times Higher Education Research Excellence Summit: Asia-Pacific to explore powerful ways universities and researchers are addressing some of the planet's most pressing issues. The event underscored the need for higher education institutions to outwardly champion the value and significance of their research.

UNSW President and Vice-Chancellor Professor Ian Jacobs led that charge when he implored higher education leaders to continue to fight for research in the public interest and to work better together, during his remarks at the opening gala dinner.

One of the challenges university leaders were facing, Professor Jacobs said, was lagging enthusiasm for public funding for universities and research. Countries such as Australia and the UK had to fight for funding and recognition of the value of universities and research, he said.

“Academics and university leaders must be proactive in sharing their stories and emphasising the link between universities and the research that, ultimately, advances society,” said Professor Jacobs. “We have to make our communities care enough to champion our work and influence the government to care as well.”

Sharing the message

During a session chaired by UNSW Science Dean Professor Emma Johnston titled 'How does research achieve public good in the 21st century context', Mark Searle, Executive Vice-President and University Provost at Arizona State University – one of UNSW’s partners in the PLuS Alliance – said higher education institutions did a poor job in helping the public understand the value-add from universities and research.

“What we do a very good job of is telling it to ourselves; the job that we do and how well we do it,” said Profressor Searle. “If we’re going to actually change that conversation, then that conversation has to have had engaged the public in a meaningful dialogue about what it is we do, why we do it and why it’s of value to them. We have a responsibility to construct the research designs in ways that actually lead down that path.”

John Gill, editor of Times Higher Education, said negative media coverage in some places around the world had contributed to the disconnect between universities and the public. In Australia, for example, the government introduced a “national interest test” to decide what research it would fund.

However, 2018 Australian of the Year and quantum computing pioneer UNSW Professor Michelle Simmons said that in her experience traveling across Australia, the public’s response to her research had been positive and supportive.

"It has been a fabulous year and people are curious, they want to know what it is we really do": 2018 Australian of the Year and quantum computing pioneer UNSW Professor Michelle Simmons in discussion at the event. Photo: Jacquie Manning

“I have been really reassured that science is something that is highly valued, innovation is highly valued,” Professor Simmons said. “One of the things that I see is that things reported in the media are not reflective of what I meet on the ground. It has been a fabulous year and people are curious, they want to know what it is we really do.”

Sir Fraser Stoddart, the 2016 Nobel Laureate for Chemistry who recently joined UNSW, said he was a great advocate for supporting people, not projects.

“My whole career has shown that project-driven research is not good value for money,” Sir Stoddart said. “The best value for money comes from giving people that are likely to have great ideas, free rope, free rein, and to just go out there and explore. This is when serendipity visits, when you’re in this land of ‘we’re having fun, we’re just doing this for the sheer love of it’.”

A changing world

Another complicating factor was the complex geo-political context the world had entered, one in which some researchers said advancement of knowledge was no longer seen as a global good.

“When one nation got better at doing things, the entire world benefitted. Geo-politics in the last decade has unfortunately moved away from that thinking and we need to be sensitive to this,” said Danny Quah, Dean and Li Ka Shing Professor in Economics at the National University of Singapore, during a speech on research and the road to prosperity in the Asian century.

Raina MacIntyre, head of the biosecurity program at the Kirby Institute and Professor of Infectious Diseases Epidemiology at UNSW. Photo: Jacquie Manning

“There are parts of the west, Donald Trump’s America for one, that believe the world is now locked in a zero-sum competition for leadership. Whether it’s leadership in technology, in 5G technology, in quantum computing, in encryption, in artificial intelligence and a range of the latest technologies. We need to build bridges, we need to work together.”

The need to build bridges was crucial in alleviating the healthcare burden of emerging economies, many of which were located in the Asia-Pacific Region, the summit heard. During the session 'What’s killing us? The age of resistant diseases', chaired by Raina MacIntyre, Head of the biosecurity program at the Kirby Institute and Professor of Infectious Diseases Epidemiology at UNSW, experts said more collaboration was needed between universities, government development partners, aid agencies and philanthropies to help inform government development priorities.

Making a real difference

During disciplinary-focused sessions, panellists and speakers delved into the real-world impacts of research. In 'Water of the future: facing the challenges', chaired by Professor Ana Deletic, UNSW Pro Vice-Chancellor of Research, experts considered the contributions of research to water resources challenges in the Asia-Pacific region.

Microfactory revolution: Professor Veena Sahajwalla, Director of the Centre for Sustainable Materials Research and Technology at UNSW. Photo: Jacquie Manning

Professor Veena Sahajwalla joined ABC journalist Sarah MacDonald for a conversation titled 'How to waste the future', which considered the need for alternative recycling practices to deal with the world’s growing waste challenge. Professor Sahajwalla revealed how the microfactory located on the UNSW campus was transforming coffee grounds and glass into new materials.

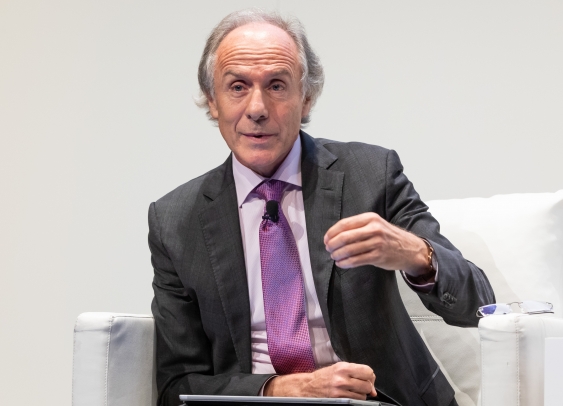

Australia's Chief Scientist Alan Finkel led a panel discussion with leaders and pioneers in the energy sector about a number of pressing challenges related to energy including the future of coal-generated energy, the renewable energy revolution and how policy and government played a role in shaping the energy sector.

What future coal? Austrtalian Chief Scientist Alan Finkel. Photo: Jacquie Manning

UNSW Professor Martin Green, Director of the Australian Centre for Advanced Photovoltaics, said figures published recently by the International Renewable Energy Agency on the amount of materials required to install each megawatt of solar photovoltaics showed renewables would create opportunities for the traditional resource exports.

“It turns out that you more than make up that $2.3 billion loss in our coal export, if you look at the same methodology for the other components that I mentioned, specifically you’ll need steel for the mounting structures, you’ll need aluminium for the frames, you’ll need copper for the wiring,” said Professor Green. “If you look at the corresponding impact upon the Australian export industry in terms of the boost you would get, it turns out in the first year you would get $7.4 billion extra export from that boost. That’s a hypothetical situation, of course.”

A revolution in exports: UNSW Professor Martin Green, Director of the Australian Centre for Advanced Photovoltaics. Photo: Jacquie Manning

Experts from three of the leading countries in the artificial intelligence space, including UNSW Professor Toby Walsh, shared their perspectives on AI research and how different nations were tackling the challenges and opportunities.

In his closing remarks, Professor Jacobs said delegates and speakers discussed how research translated into a public good in multiple ways from massaging baby rats to understanding how what threatens us is changing – from old threats like infectious diseases to new threats, and potential threats, such as those brought on by political crises such as Brexit or technological frontiers such as the development of AI.

“We have reinforced the value of fundamental discovery research. We have reinforced the importance of linking our research and educational efforts more closely,” Professor Jacobs said. “And we have formed a consensus in the room, that the research produced in our part of the world has enormous potential yet to be tapped.”