If needed, this man can and will cut rates during the election campaign

In his regular column, Vital Signs, UNSW Business School academic Richard Holden discusses Reserve Bank governor Philip Lowe.

In his regular column, Vital Signs, UNSW Business School academic Richard Holden discusses Reserve Bank governor Philip Lowe.

It was a great story.

Philip Lowe had taken over as Reserve Bank governor after 25 years of uninterrupted economic growth. The Australian economy was transitioning nicely away from the country’s biggest-ever mining boom. Interest rates had been cut to historic lows in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis and had bottomed out. Inflation and wages growth were about to pick up. Unemployment was falling. And the new governor would preside over a return to “new normal”, with gradual rate rises up to a cash rate of 3.5-4.0%.

Then a funny thing happened on the way to the fairytale ending.

In a remarkable speech at the National Press Club on Wednesday, Lowe essentially admitted that the bank might well need to take extra remedial action to get the economy moving again.

Gone was the mantra that “the next movement in interest rate will likely be up”. Rather, Lowe said:

…here are scenarios where the next move in the cash rate is up, and other scenarios where it is down. Over the past year, the next-move-is-up scenarios were more likely than the next-move-is-down scenarios. Today, the probabilities appear to be more evenly balanced.

Translation: “I don’t want to freak you out, but we’re probably going to have to cut rates. And do it sooner rather than later.”

Consider the two main things driving the Reserve Bank’s decision.

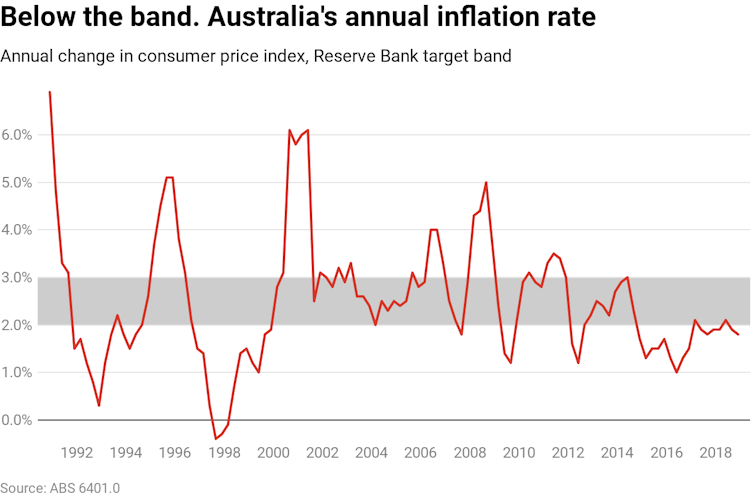

Inflation is stubbornly low. As I pointed out last week, the bank has long had an inflation target of 2-3%, but it keeps undershooting it, and not just missing the centre, but missing the lower bound. In two and a half years with Lowe as governor, inflation has averaged just 1.87% – and has never been inside the target band. The latest figure is 1.8%.

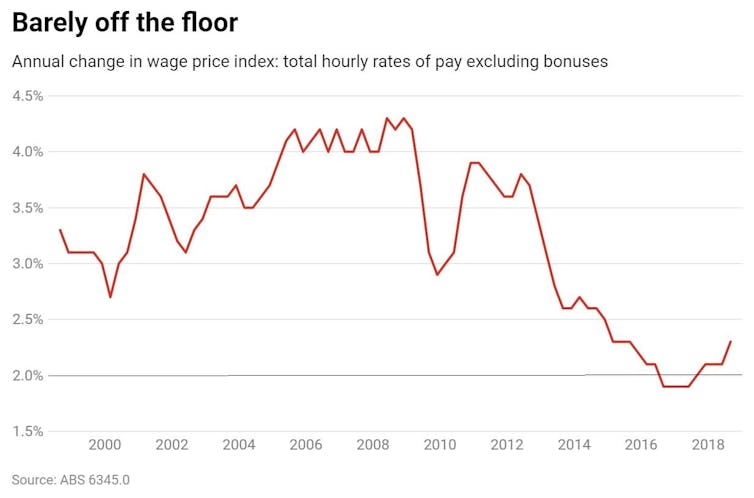

Related to that, wages growth is anaemic. For five years it has barely kept up with inflation.

This is broadly true in advanced economies around the world (although our wages are doing worse than those in the United States) and suggests the unemployment rate will need to be pushed down further than in the past in order to reignite wages pressure and hence inflation. That suggests we’ll need even lower interest rates than we’ve got in order to provide what the boffins call monetary stimulus.

And the Reserve Bank’s cash rate — the rate that most other rates are set in reference to — is already the lowest on record, at just 1.5%.

Meanwhile, the housing market has taken a big hit, which isn’t over. Nationwide, the market is down 6.1% from its October 2017 peak. In Sydney and Melbourne, the falls are double that.

They are the mainly the result of a credit crunch that flowed from the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority’s decision to wake from its multi-year slumber and tighten lending rules at about the same time the banks responded to the royal commission by impersonating frightened turtles.

Sliding property prices shrink household spending, which makes up roughly 60% of economic activity.

On Tuesday, in the statement it released after its first board meeting for the year, the bank obliquely signalled that it had cut its GDP growth forecasts, mentioning forecasts of 3% this year and less in 2020 instead of the 3.5% this year and less in 2020 it had mentioned after its December meeting.

Add in the global headwinds from the US-China trade tensions and the fallout from the bungled Brexit, and it’s hard to find much that’s encouraging about the Australian economy in the year ahead.

Lowe didn’t want to state explicitly that he might have to cut rates between now and the election (and if necessary during the campaign itself), but he didn’t need to. He has been as clear as governors get.

A decent bet is the bank will cut 25 points on the first Tuesday in May, after the release of the updated (and possibly weak) inflation data on April 24.

Another possible date is the first Tuesday in April, April 2, after the March release of the December quarter economic growth figures, especially if economic growth turns negative. Coincidentally, April 2 is the day the government has set aside for the early budget, so it can hold the election in May.

If it does there will be some who will try to spin it as good news. In 2007 John Howard campaigned under the slogan that rates would be “lower under the Coalition”.

His treasurer Peter Costello was under the impression the bank wouldn’t dare move rate during the campaign, unwisely telling broadcaster Jon Faine it would keep them put.

“He looked me in the eye. He put his thumb down as he sat there…and he said, ‘There will not be a rate rise in November. Take it from me’,” Faine said.

Having marked out the territory, there is no doubt the bank will use it if needed. To do otherwise would be to invite questions about whether it had favoured one party or the other by holding off.

The hard truth is that we live in a secular-stagnation world, with too much saving chasing too few profitable investment opportunities.

That means that interest rates don’t need to be anything like as high as they once did to attract enough money to fund good ideas. And even if the ideas are good, it is likely they won’t need as much money as they did. Whereas once it took tens of billions of dollars to create a globally significant company (like BHP or US Steel) all it takes now is maybe $2,000 and a laptop, as with Facebook and Google.

A massive mining boom caused by the transition of China to a market economy and then a huge property bubble masked the new reality here for while.

Now it is here for all to see, the Reserve Bank governor included.

Richard Holden, Professor of Economics, UNSW

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.