Finding help in the city: professor advocates for the world's urban refugees

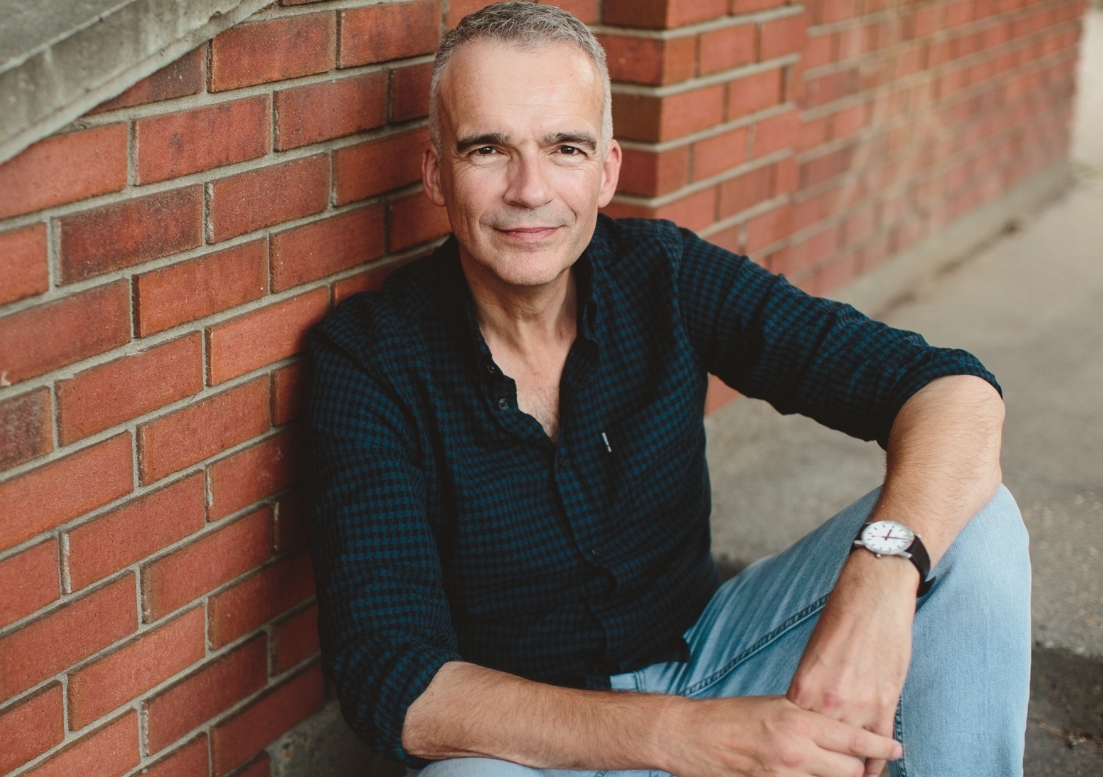

UNSW Professor David Sanderson launches his book A Good Practice Review in Urban Humanitarian Response on World Humanitarian Day.

UNSW Professor David Sanderson launches his book A Good Practice Review in Urban Humanitarian Response on World Humanitarian Day.

There are more refugees today than in any time since World War II. The United Nations Refugee Agency estimates that of the 70 million or so people who have been forcibly displaced from their homes, 23 million are refugees – people who have fled their home country due to factors including violent conflict, environmental and climate issues, human rights violations and famine.

Across the globe, from Kenya to Bangladesh, giant camps have been built to accommodate them. It’s images of sprawling tent cities that most people picture when they think of refugees. But most refugees do not live in camps. The UN estimates that globally over 60 per cent of refugees choose to live in towns and cities.

In his new book, A Good Practice Review in Urban Humanitarian Response, UNSW Built Environment Professor David Sanderson, inaugural Judith Neilsen Chair in Architecture, offers practical guidance for managers in designing, implementing and monitoring humanitarian aid programmes in urban contexts. The book was commissioned by Humanitarian Practice Network (HPN) at the Overseas Development Institute (ODI) and the Active Learning Network for Accountability and Performance in Humanitarian Action (ALNAP).

The book launch in Canberra today coincides with the United Nations’ World Humanitarian Day, held every year on 19 August to pay tribute to aid workers who risk their lives in humanitarian service, and to rally support for people affected by crises around the world.

Professor Sanderson, who is leading the UNSW Grand Challenge on Rapid Urbanisation, said displacement is increasingly an urban phenomenon, with more and more displaced people seeking shelter and employment in towns and cities rather than camps.

What’s more, by 2045 the prediction is that there will be six billion people living in cities, with most growth taking place in Asia and Africa. Still, most humanitarian aid plans are geared toward a rural response. A number of aid organisations are now seeking to urbanise their approaches. Professor Sanderson said the complexity of cities must be engaged and embraced, not something to push against. He said the aim is for cities and urban areas to work with entrepreneurs and people with skillsets that can assist with recovery, rather than assuming aid organisations will provide solutions.

“We’re living at a time where more people are being pushed out from where they live than ever before around the world as refugees or as migrants,” Professor Sanderson said. “At the same time, we have an aid system that is largely based on rural expertise and so the idea behind this Good Practice Review is to urbanise our urban humanitarian response.”

The Good Practice Review is structured into four chapters that define cities, identify themes and issues, provide frameworks and standards, and summarise the current humanitarian system. The research is drawn from reports, journals and academic papers. Online searches were made using existing databases, online libraries and dedicated journals, and expert organisations and individuals were also contacted for sources and inputs, alongside an advisory committee of 16 members comprising experienced practitioners, consultants and academics. As well as refugees, the book covers disasters, conflict and violence in cities.

“The hope for the publication is that it is used, is found to be practical and valuable by those who are seeking to provide good response,” Sanderson said. “In the next 25 years, there are going to be nearly 2 billion extra people living in cities. If those predictions are correct, we need to learn for the future and get better at what we do.”

The Grand Challenges Program has been established to facilitate critical discussions and raise awareness of the ground-breaking research and initiatives undertaken by UNSW academics, staff and students.

Tickets to the book launch are free and registrations is available via UNSW Events.