Reuben follows grandfather's tracks in world solar car challenge

UNSW students will take on some of the world's brightest minds in solar car engineering when they leave Darwin on Sunday for the 15th Bridgestone World Solar Challenge.

UNSW students will take on some of the world's brightest minds in solar car engineering when they leave Darwin on Sunday for the 15th Bridgestone World Solar Challenge.

When UNSW engineering student Reuben Hackett takes the wheel of team Sunswift’s solar car at the start of the Bridgestone World Solar Challenge (BWSC) in Darwin this Sunday, one special fan will be watching closely.

Mr Hackett’s grandfather, electrical engineer Alex Hromas, helped to design and drive one of the first solar cars entered into the 3000km race from Darwin to Adelaide, when it was first staged in 1987.

“I’d just designed a solar electric power system for a consulting job, so my friend asked me to help build a car for this new race,” Mr Hromas says. “All the cars back then were single-person race cars; they were very lightweight. The roads were a bit hairy too – there was a single strip of bitumen and a lot of road trains.

“The organisers ran a stability test before the race by driving a B-double [semi-trailer] at us at 140km/h and if we didn’t flip over in the wind buffet, we were good to go.”

Thankfully, the highway has improved in the past 32 years for the 40-plus teams who come from some of the world’s leading universities and research institutes to compete in the biennial event.

'The organisers ran a stability test before the race by driving a B-double [semi-trailer] at us at 140km/h. If we didn’t flip over in the wind buffet, we were good to go.'

Mr Hackett will be driving UNSW Sunswift’s car, named Violet, which was built entirely by students, in the Cruiser Cup category. Entrants are judged on energy efficiency as well as other factors such as design innovation, occupant space and comfort, and environmental impact.

While the UNSW team has been relatively successful in previous Challenges, it was forced to withdraw from the 2017 event due to a rear suspension failure. Since then, team members have made a raft of improvements to Violet. Team mentor, UNSW Professor of Practice Richard Hopkins, is confident the car will be a strong contender in this year’s race.

UNSW Sunswift's redesigned solar car, Violet.

"The team has practically re-built Violet since the 2017 race, and driven her over 4000km from Perth to Sydney to set a new world record in efficiency last year. I think we can be very confident that she’ll make it to the finish line next week,” Professor Hopkins says.

In a push from organisers to make the event more realistic this year, a new rule restricts competitors to just two charging opportunities – at Tennant Creek and Coober Pedy. This means the teams will have to travel about 1000km on a single charge.

Mr Hackett says the new rule will make it more challenging for everyone to finish the race.

“In previous years, we’ve been able to charge our battery whenever we wanted to,” Mr Hackett said. “We’ll now have to monitor our speed and power consumption more carefully than ever before, to make sure we don’t run out of power short of the designated charging stations.

The teams will have to travel about 1000km on a single charge.

“In terms of energy management, especially if it’s cloudy – or worse, if it rains – we’ll either have to try to beat the clouds or go slower to conserve energy.”

Fortunately for Mr Hackett and his fellow driver, 19-year-old Jed Cruickshank (the two will alternate in two-hourly shifts), there’ll be a team of about 25 fellow students supporting them on the road to Adelaide.

The students, from the faculties of Art & Design, Business, Engineering and Science, all volunteer to fill various roles on the Sunswift team, including technical, product design, marketing and project management. While a UNSW staff member will be with the team, the students are responsible for every aspect of the journey, down to the amount of tinned food they’ll be bringing along to sustain them.

“We are really well prepared and I think Violet would have to be one of the most tried and tested cars in the race. I’m feeling confident we can take the chequered flag in Adelaide on Friday,” Mr Hackett says.

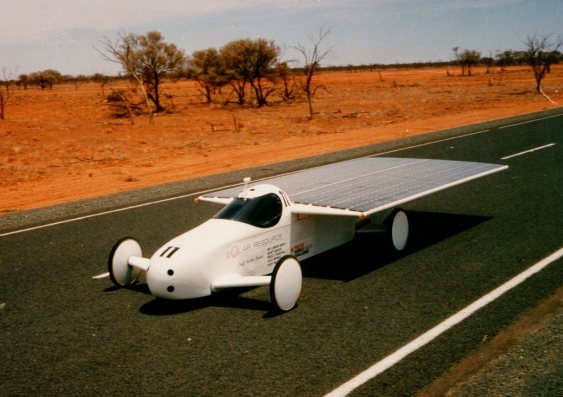

Alex Hromas's car, Solar Resource, in the first World Solar Challenge in 1987. Photo by Ian Landon Smith, courtesy of MASS

In his last piece of advice to his grandson, Mr Hromas encouraged Mr Hackett to enjoy every minute of the Challenge.

“When Reuben went to university at UNSW, I told him to get involved with Sunswift because it’s a way of meeting people from a lot of different faculties and disciplines. I knew this would give him a much wider education base and a bit of cross-cultural experience, rather than just sitting in engineering classes,” Mr Hromas says.

“To be a successful engineer, you have to be able to appreciate other things, as well as the straight nuts and bolts of engineering. Without that wider view of society, you’re never going to be a good engineer.

“I’d like to see Reuben and his teammates have as much fun as they possibly can.”

From 2020, second-, third- and fourth-year engineering students will be able to apply to be part of the Sunswift team and gain academic credit, as part of the new ChallENG program.