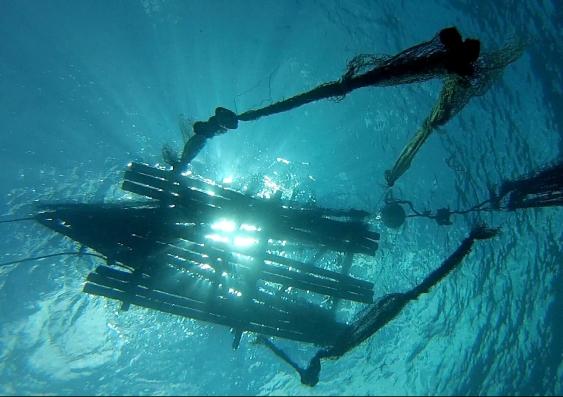

Fish are attracted to floating objects, especially with dangling ropes or nets. WorldFish/Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA

Tropical tuna are one of the few wild animals we still hunt in large numbers, but finding them in the vast Pacific ocean can be tremendously difficult. However, fishers have long known that tuna are attracted to, and will aggregate around, floating objects such as logs.

In the past, people used bamboo rafts to attract tuna, fishing them while they were gathered underneath. Today, the modern equivalent – called fish aggregating devices, or FADs – usually contain high-tech equipment that tell fishers where they are and how many fish have accumulated nearby.

It’s estimated that between 30,000 and 65,000 man-made FADs are deployed annually and drift through the Western and Central Pacific Ocean to be fished on by industrial fishers. Pacific island countries are reporting a growing number of FADs washing up on their beaches, damaging coral reefs and potentially altering the distribution of tuna.

Our research in two papers, one of which was published today in Scientific Reports, looks for the first time at where ocean currents take these FADs and where they wash up on coastlines in the Pacific.

Attracting fish and funds

We do not fully understand why some fish and other marine creatures aggregate around floating objects, but they are a source of attraction for many species. FADs are commonly made of a raft with 30-80m of old ropes or nets hanging below. Modern FADs are attached to high-tech buoys with solar-powered electronics.The buoys record a FAD’s position as it drifts slowly across the Pacific, scanning the water below to measure tuna numbers with echo-sounders and transmitting this valuable information to fishing vessels by satellite.

Throughout their lifetimes FADs may be exchanged between vessels, recovered and redeployed, or fished and simply left to drift with their buoy to further aggregate tuna. Fishers may then abandon them and remotely deactivate the buoys’ satellite transmission when the FAD leaves the fishing area.

The Western and Pacific Ocean provides around 55% of the worlds’ 5 million tonne catch of tropical tuna, and is the main source of skipjack, yellowfin and bigeye tuna worth some US$6 billion annually.

Fishing licence fees can provide up to 98% of government revenue for some Pacific Island countries and territories. These countries balance the need to sustainably manage and harvest one of the only renewable resources they have, while often having a limited capacity to fish at an industrial scale themselves.

FADs help stabilise catch rates and make fishing fleets more profitable, which in turn generate revenue for these nations.

However, they are not without problems. Catches around FADs tend to include more bycatch species, such as sharks and turtles, as well as smaller immature tuna.

The abandonment or loss of FADs adds to the growing mass of marine debris floating in the ocean, and they increasingly damage coral as they are dragged and get caught on reefs.

Perhaps most importantly, we don’t know how the distribution of FADs affects fishing effort in the region. Given that each fleet and fishing company has their own strategy for using FADs, understanding how the total number of FADs drifting in one area increases the catch of tuna is crucial for sustainably managing these valuable species.

Where do FADs end up?

Our research, published in Environmental Research Communications and Scientific Reports, used a regional FAD tracking program and fishing data submitted by Pacific countries, in combination with numerical ocean models and simulations of virtual FADs, to work out how FADs travel on ocean currents during and after their use.

In general, FADs are first deployed by fishers in the eastern and central Pacific. They then drift west with the prevailing currents into the core industrial tropical tuna fishing zones along the equator.

We found equatorial countries such as Kiribati have a high number of FADs moving through their waters, with a significant amount washing up on their shores. Our research showed these high numbers are primarily due to the locations in which FADs are deployed by fishing companies.

In contrast, Tuvalu, which is situated on the edge of the equatorial current divergence zone, also sees a high density of FADs and beaching. But this appears to be an area that generally aggregates FADs regardless of where they are deployed.

Unsurprisingly, many FADs end up beaching in countries at the western edge of the core fishing grounds, having drifted from different areas of the Pacific as far away as Ecuador. This concentration in the west means reefs along the edge of the Solomon Islands and Papua New Guinea are particularly vulnerable, with currents apparently forcing FADs towards these coasts more than other countries in the region.

Overall, our studies estimate that between 1,500 and 2,200 FADs drifting through the Western and Central Pacific Ocean wash up on beaches each year. This is likely to be an underestimate, as the tracking devices on many FADs are remotely deactivated as they leave fishing zones.

Using computer simulations, we also found that a significant number of FADs are deployed in the eastern Pacific Ocean, left to drift so they have time to aggregate tuna, and subsequently fished on in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean. This complicates matters as the eastern Pacific is managed by an entirely different fishery Commission with its own set of fisheries management strategies and programmes.

Growing human populations and climate change are increasing pressure on small island nations. FAD fishing is very important to their economic and food security, allowing access to the wealth of the ocean’s abundance.

We need to safeguard these resources, with effective management around the number and location of FAD deployments, more research on their impact on tuna and bycatch populations, the use of biodegradable FADs, or effective recovery programs to remove old FADs from the ocean at the end of their slow journeys across the Pacific.

Joe Scutt Phillips, Senior Fisheries Scientists (Tuna Behavioural Ecology), Secretariat of the Pacific Community; Alex Sen Gupta, Senior Lecturer, School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences, UNSW; Graham Pilling, Principal Fisheries Scientist, Secretariat of the Pacific Community, and Lauriane Escalle, Fisheries Scientist, Secretariat of the Pacific Community

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.