A new experimental electronic music album, Microphone Permission, gives sound to the data collection that occurs online and in our smart cities daily.

Literally disquieting, Jasmine Guffond’s fourth solo album invites listeners to consider the implications of invasive contemporary digital listening practices.

The result, according to label Editions Mego which released the album this month, is “a stark, brooding, disorientating journey into a paranoid musical field that sits somewhere between ambient club music and a dystopian soundtrack”.

The album draws on several of Ms Guffond’s projects developed over the past two years, including an installation that gives sound to the Twitter feeds of Donald Trump, Justin Bieber, Taylor Swift and others; an add-on for Firefox and Chrome that translates cookies into sound as you browse online, exposing digital surveillance in real time; and a project that sonifies datasets counting pedestrians through the City of Melbourne.

“We are tracked both online and in our cities,” the UNSW Art & Design PhD candidate says. “And we watch and monitor each other so much on social media…

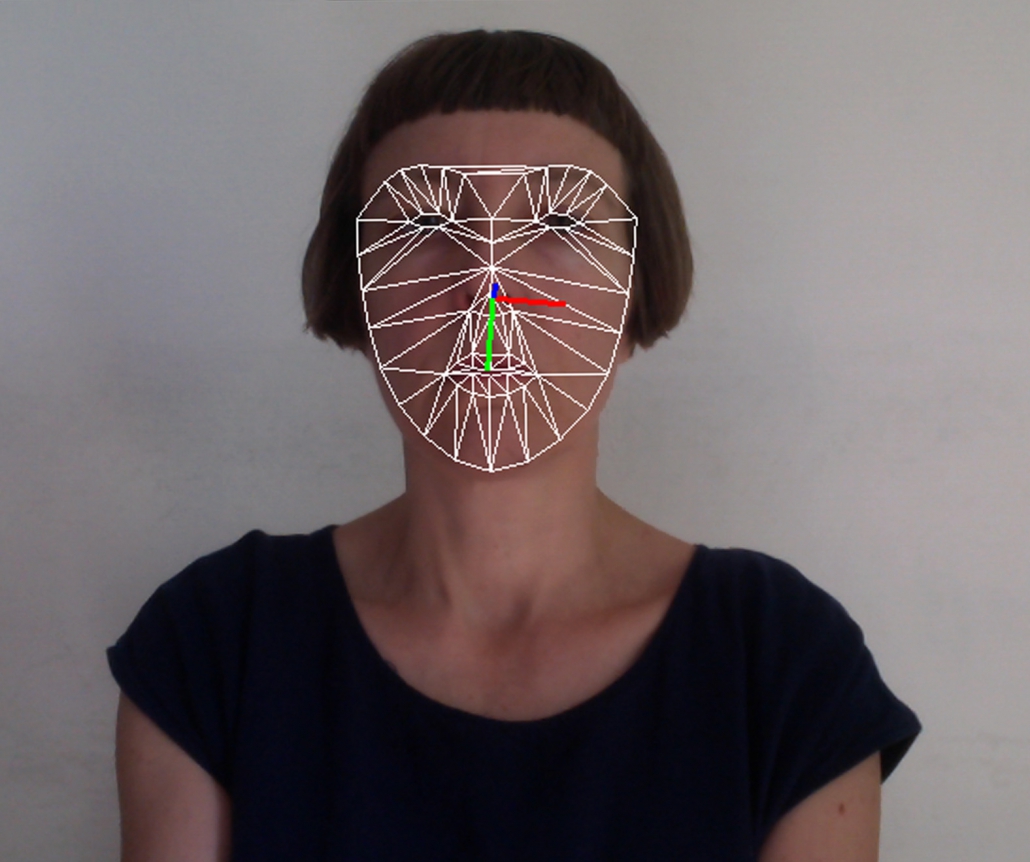

“I’m drawn to give sound to things usually beyond human perception – facial recognition algorithms, global networks or internet tracking cookies – and to question what it means for our personal habits to be traceable and our identities, choices and personalities to be reduced to streams of data.”

Microphone Permission refers to the consent given by smart device users when installing certain apps. The name was inspired by a 2018 scandal when La Liga, an app for Spanish soccer fans, was discovered to be using microphone access and GPS location to catch out bars broadcasting soccer matches without the correct licence, turning app users into unwitting spies.

In her PhD thesis, Ms Guffond uses sound as a method of investigating this culture of covert online surveillance.

“Media art has the ability to make the invisible visible, the unknowable knowable to its audience,” her supervisor, Dr Caleb Kelly, says.

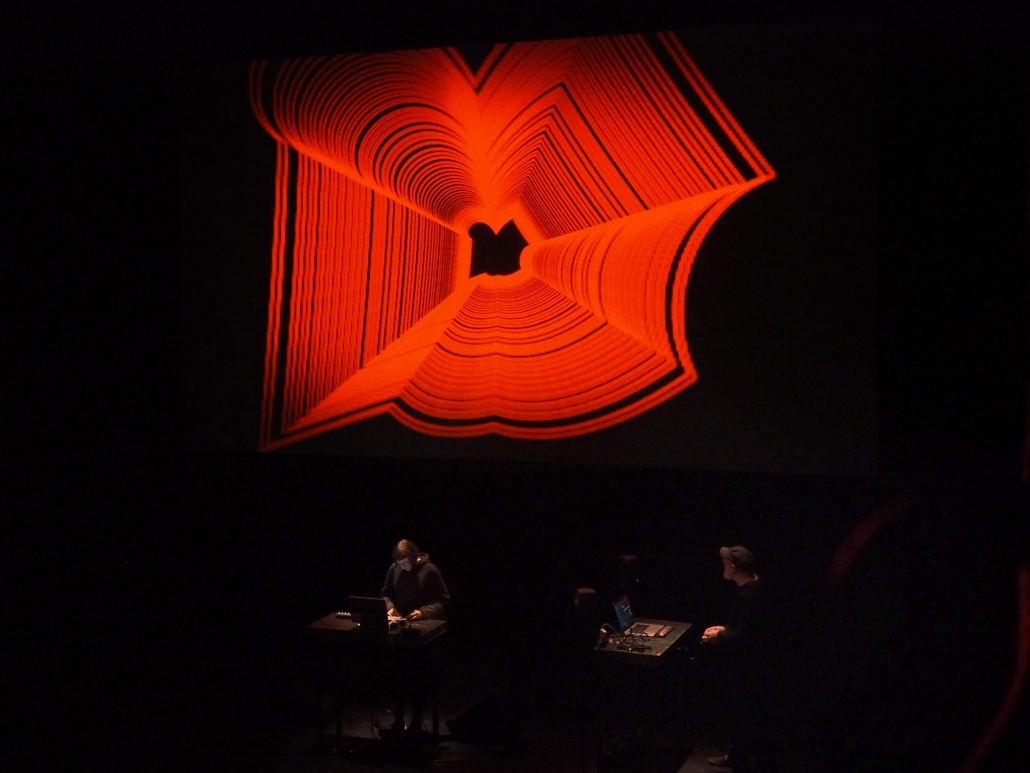

This kind of “practice-led knowledge creation allows for a tactile and generative form of knowing. It’s different to reading about it. When attending Jasmine’s performances, the audience is enveloped in sound and through this experience comes to know the work through the senses”, the Associate Professor in Media Arts & Art Theory says.

“Not harsh or brutal but full and immersive, we hear surveillance as electronic music,” he says.

The silent technology of facial recognition as inspiration

The inspiration for exploring online surveillance through her music came when Ms Guffond was studying a Masters in Sound Studies in Berlin in 2013-2015. The students created a soundwalk at the German Opera House about the history of protest in Berlin.

“All protests in Germany are videoed by the police who have the capacity [with facial recognition technology] to crosscheck the captured footage with databases of drivers licenses and photo ID,” she says.

With facial recognition, “it’s different from other biometric surveillance where you have to actively give over your fingerprint or look into a camera for an iris scan... It’s considered to be a silent technology, so that’s why I thought it's important to give it a sound,” she says.

When participants in the soundwalk handed in their ID card to receive their headset, Ms Guffond and some fellow students created one-minute pieces of “face music”, using a piano midi sound to translate the facial data detected on their photo IDs. Each piece was burnt onto a CD and given to participants at the end of the walk.

“A lot of the people were older – because it’s an older audience at the opera – and they hadn’t heard of facial recognition technology,” Ms Guffond says. “That was one of the most rewarding things about the project – the conversations we had at the end of the walk about contemporary digital surveillance.”

An art practice that embraces diverse forms

This initial project sparked two years of sound investigations and installations, some of which have made their way onto Microphone Permission, including a dance performance about the future sounds of an extinct forest, a composition for a theatre piece about music and feminism in Western Sydney, and a site-specific installation at the Linachtalsperre Dam in the Black Forest that used the harmonic frequencies of electric currents.

Each sonification project starts with the dataset and the desire to create an iconic sound for its representation, Ms Guffond says. In the installation that sonified Twitter metadata, she used the datasets available on the Twitter API (application programming interface) – the data Twitter gives third-party developers access to.

She chose Twitter profiles with a lot of followers – Donald Trump, Narendra Modi, Lady Gaga, CNN and others – because their feeds provided a steady flow of data for the sound installation. Each time there was a reply or retweet to one of these profiles’ tweets, a different sound was triggered according to the action and the device used (iPhone, Android, Windows etc).

“I created individual sounds using triangle, sine, saw waves and white noise. These were modulated using envelop filters and pitched according to different scales,” she says. “I created families of sounds for each profile founded on pitch, scale and timbre.

“It was interesting to note how much space celebrities take up in the Twittersphere, especially Trump. I could have made an installation solely from the data generated by his profile. At times there would be an avalanche of sound and I would check the news and he would have just made a public statement about the Iran nuclear deal for example, which had an ominous effect on the listening experience.”

A fascination with sound from an early age

Ms Guffond has always experimented with sound. In primary school she submitted willingly to the obligatory recorder lessons – “I didn’t really mind them” – as well as playing classical flute.

“I found learning scales really tedious though,” she says. “That’s what drew me to electronic music – the fact that I could use anything that existed in the world in my sampling.”

By the time she left school, she was playing in bands and collaborating with other local electronics artists. In post-techno band Alternahunk, she played bass and created “homemade electronics using toys that made sounds and guitar pedals to generate noise”. In electronics duo Minit with Torben Tilly, she performed on her 16-bit AKAI S1000 stereo digital sampler at eclectic art spaces like Imperial Slacks, Surry Hills for the Impermanent Audio sound series.

Her first public performance at the Jellyheads warehouse was a “kind of horrible experience”, she says. “It was the first time I’d made that transition from the practice space to the live space, and it was a very DIY space where you couldn’t hear yourself – I felt like I didn’t know what I was doing.”

From small venues and pubs to dance parties in alternative off-spaces in Sydney and Melbourne, this year she opened the contemporary electronic, digital and experimental music festival CTM in Berlin with work from Microphone Permission, playing twice to a packed theatre of 490 people. But the journey has been measured.

While the nerves are still there, now there is less chaos, more focus.

Moving to Berlin in 2003 gave her a “sense of freedom” artistically. It allowed her to “focus more on an art context and develop new ideas, [rather than] just playing live shows and recording records, outside my hometown”.

From Sydney to Berlin and all the places in between

Since then her art practice has taken her around the globe from Sydney to an abandoned elementary school in Chicago, to the Prison Palace (famous for incarcerating Casanova) at the Venice Biennale, to Auckland and Brussels and of course Berlin – and that is just in the last few years.

“Jasmine has been making electronic music for over 25 years and internationally she is one of our most highly regarded media artists,” Dr Kelly says. “Her work can be brutal in its tonal range while immersing the audience in waves of sonic pressure that are beautiful and transfixing.”

In April, she will play live in Perth at the Audible Edge Festival, and in May she comes home to Sydney to play Humming Grotto, an “evening of electronics/energies/bread/voice/other” downstairs at the PBC (or the Petersham Bowling Club for the uninitiated).

So how do you thwart online surveillance technologies?

Like billionaire Mark Zuckerberg, Ms Guffond keeps a sticker over her camera. “It’s easy,” she says. “And it can’t hurt.” Plus, after watching Snowden, Oliver Stone’s dramatisation of Edward Snowden’s life, she is aware that breaches in privacy can and do happen, she says.

She has tracking blockers installed as plug-ins on her computer and she uses startpage.com as her web browser which utilises Google’s search engine while anonymising your IP address.

Wherever possible, she uses a “dumbphone”, network permitting. And she definitely does not give microphone permission.

Microphone Permission is out now on Editions Mego.