When it comes to sick leave, we're not much better prepared for coronavirus than the US

One quarter of Australian workers have no paid sick leave. They are more likely than most to work in service industries, dealing with people face to face.

One quarter of Australian workers have no paid sick leave. They are more likely than most to work in service industries, dealing with people face to face.

The problem now and going forward is making sure that sick workers stay home. That means not forcing employees to choose between penury and working while coughing.

That’s the conclusion from an editorial in last week’s New York Times that notes that one in four American private sector workers are not entitled to paid sick leave.

“They face a choice between endangering the health of co-workers and customers, and calling in sick and losing their wages and perhaps also their jobs,” it says.

The people least likely to have paid sick days, and so most likely to work through illness, are low-wage service workers such as restaurant employees and home health care aides. In the United States, they are also less likely to have health insurance and so less likely to seek assistance.

The editorial suggests that paid sick leave be mandated, and that the US government meet some of the cost, by for example providing big businesses with a one-off tax credit and providing smaller companies with direct support.

In Australia we like to think we have a better social safety net than in the US, and in the case of health coverage, we do. But in other ways we are just as as unprepared.

In Hobart on Sunday health authorities said a man infected with coronavirus ignored instructions to self-isolate while he waited for his test results because he didn’t want to miss his casual shifts at Hobart’s Grand Chancellor Hotel.

The Bureau of Statistics Characteristics of Employment Survey shows that in 2019, 24.4% of Australian employees were casuals without any access to paid leave.

Adding in the self-employed, the proportion of all Australian workers without paid sick leave would be 37%.

As the chart shows, Australians without paid sick leave are over-represented in some of the sectors with the greatest degree of personal contact with members of the public.

63% of people working in the accommodation and food services sector have no paid sick leave, and 45% of sales workers and 42% of community and personal service workers.

Proportion of workers in each industry without paid leave

Proportion of employees without paid leave entitlements by industry, 2019. ABS 6333.0Casual workers also have less ability to work from home.

About 30% of employees with paid sick leave were able to regularly work from home, compared to 10% of those without paid sick leave.

Permanent employees are entitled to at least 10 days per year of paid sick and carer’s leave at their base rate of pay and usual hours.

Separately, all employees – including casuals – are entitled to two days unpaid carer’s leave or compassionate leave. But given that it is unpaid, it doesn’t deal with the financial problems that sick and potentially infectious casual workers will face.

What support does Australia have for those people not entitled to paid sick leave?

Not much at all.

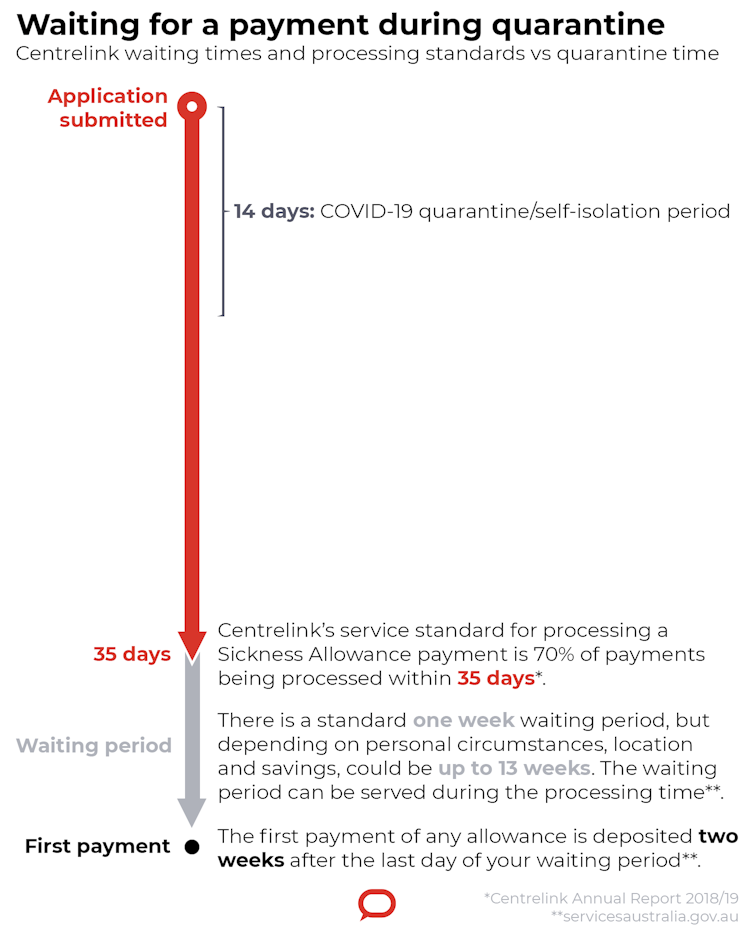

People who can’t work in their job because of illness can currently apply for Sickness Allowance - which will be phased out starting on March 20 and subsumed into a broader jobseeker payment with similar conditions.

Sick claimants face a waiting period of one week, plus an extra waiting period of up to 13 weeks if they have readily available financial assets of $5,000 or more.

(The government has announced its intention to increase the waiting period to up six months for people with more than $18,000 in savings.)

With such tight eligibility conditions, it isn’t surprising that few people claim sickness allowance; only 5,000 in June 2019.

It is paid at the same rate as Newstart - less than 40% of the minimum wage, which even taking into account assistance with housing costs, turns out to be the lowest level of income replacement for an unemployed person in the OECD.

If that person’s spouse is working, the income test might lead to them receiving no payment or a much-reduced payment.

The government has indicated that it is not planning to increase the inadequate rate of Newstart, probably in order to avoid a long-lasting boost to government spending. However, it might make one-off payments to people receiving income support - an approach supported by the Australian Council of Social Service.

It could also lift Newstart and associated benefits on a temporary basis. People on these benefits make up about 12% of part-time workers and are highly likely to be casuals. The Council of Small Business Organisations wants waiting periods waived.

In addition we could do what the New York Times proposes in the US.

Encouraging employers to provide sick pay to casual workers would be in keeping with our long history of employer-provided sickness benefits. The government could reimburse employers for large chunk of the costs.

We already have a model for it. The paid parental leave scheme introduced in 2011 provides eligible working parents with up to 18 weeks of taxpayer-funded leave at the national minimum wage, whether they are full-time, part-time, casual, seasonal, contract or self-employed.

We could do it only temporarily, during the coronavirus crisis, while we consider more permanent support for our growing casual workforce.

The appropriate response to a pandemic is in one important way quite different to the response to a recession. The aim in a recession is to keep people attached to the labour market and allow their employers able to continue to trade. The aim in a pandemic is to support people to stay away from workplaces.

The way to do it is an immediate sickness payment, without a waiting period, that is big enough to keep people who should be quarantined away from work.

Peter Whiteford, Professor, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University and Bruce Bradbury, Associate Professor, Social Policy Research Centre, UNSW

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.