Vital Signs: APRA's extraordinary gift to banks under pressure to pay dividends

APRA is allowing the big four banks to coordinate in a way that might otherwise be illegal.

APRA is allowing the big four banks to coordinate in a way that might otherwise be illegal.

Last week the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) sent an extraordinary letter to Australia’s banks and insurers, essentially telling them to cut their dividend payments to shareholders in light of the coronavirus crisis.

It said it expected banks and insurers to “seriously consider deferring decisions on the appropriate level of dividends”.

APRA letter to financial institutions, April 7, 2020Where a board was confident that it could approve a dividend on the basis of robust stress testing that had been discussed with APRA, it should “nevertheless be at a materially reduced level”.

Where dividends were paid those payments should be “offset to the extent possible through the use of dividend reinvestment plans and other capital management initiatives”.

With Australia’s big four banks potentially suffering big losses due to mortgage defaults among other things, their capital bases are at risk.

Equity research analysts at Macquarie outline a scenario under which bank losses

reach A$25-27 billion per bank, and their capacity to pay dividends (without raising equity) materially diminishes

The letter isn’t a “ban” on dividends, and APRA wasn’t telling the banks anything they don’t already know. So why did it bother?

The answer lies in the economics of how investors react to firms that don’t pay the dividends expected.

Seen through that lens, APRA was very clever indeed.

In a classic 1985 paper Merton Miller and Kevin Rock provided a theoretical answer to the puzzle of why paying dividends seems to signal good news to investors, and why cutting dividends seems to signal bad news, and cuts the share price.

In the Miller-Rock model, the managers of a firm have better information about its future prospects than outside investors.

To keep it simple, imagine there are two “types” of firms: good and bad.

Good firms have high future cashflows, bad ones have low ones.

Only the managers know which is which.

Because both types of firm can earn something from investing in the business, it is in the interest of both (more so the good firm) to invest rather than pay out dividends.

Miller and Rock wondered whether what each type of firm did provided clues to investors about whether the managers thought it was good or bad.

Surprisingly, they found that usually good firms will pay high dividend and bad firms no dividends.

It is surprising because good firms are sacrificing more by paying dividends.

Their logic was that the bad firms were the least able to afford good dividends and that good firms knew this and paid high dividends to signal they could afford to.

It has a striking implication with strong empirical support.

If a firm gets a temporary negative shock to its cashflow or investment prospects it won’t want to cut its dividend lest investors think it has turned “bad”.

It will borrow or even do short-term damage to its prospects in order to maintain investor confidence and hence a high stock price.

Notice that the signalling theory of dividends implies that the managers of firms would like to cut dividends in tough financial times, and probably should, but they worry about sending a bad signal to investors.

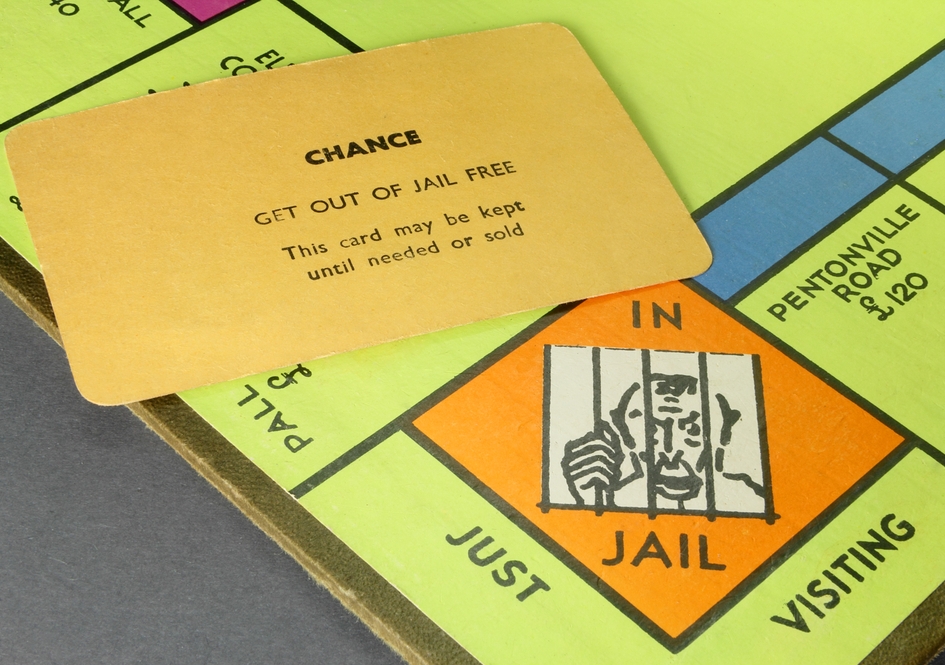

APRA’s letter is a get-out-of-jail card.An announcement like APRA’s provides them with cover – an excuse.

And it does more. It is what economists refer to as a “coordination device”.

If the big four banks got together and agreed cut their dividends by the same amount, say in half (which would be illegal) investors would get no differential signal and no new information about which bank was “good” and which was “bad”.

APRA’s message opens up the possibility of all four coordinating without talking – merely by following advice.

As 2005 Nobel laureate Thomas Schelling put it in his book, The Strategy of Conflict,

people can often concert their intentions or expectations with others if each knows that the other is trying to do the same

And they’ve an interest in coordinating. If one bank falls over during this crisis and needs to be bailed out that’s bad for all of them. All of their stock prices will tank, it will be hard for them to raise the capital they need to fund their operations.

Australia’s banks compete, but they are “frenemies”, right now more friends than enemies.

We will have to wait and see if they pick up the get-out-of-jail card APRA has handed them and cut dividends together.

APRA could have taken a tougher stance. It could have banned dividends. But that would have sent a bad signal to domestic and international capital markets about the solvency of our banks.

I have been critical of some of APRA’s moves in recent years. But this one is brilliant. Let’s hope the banks can see a life raft when they’re offered one.

Richard Holden, Professor of Economics, UNSW

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.