Is it time for a new accord between trade unions and employers?

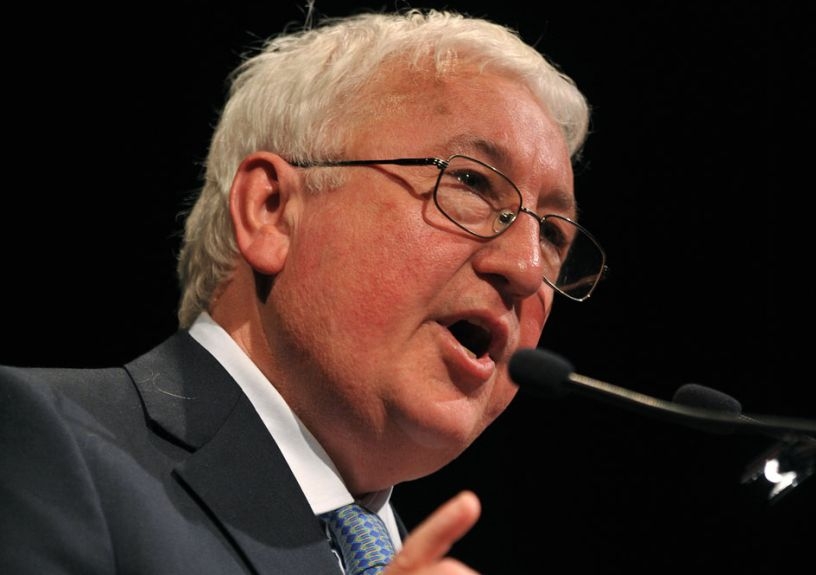

Can the PM take a leaf from Bill Kelty’s book on industrial relations reform and bring the trade union movement together through social solidarity?

Can the PM take a leaf from Bill Kelty’s book on industrial relations reform and bring the trade union movement together through social solidarity?

Following successful COVID-19 crisis leadership, Prime Minister Scott Morrison recently proposed that employer groups and the Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU) negotiate a new Industrial Relations (IR) framework for the post-COVID-19 labour market under the guidance of IR Minister Christian Porter.

He did this having already worked closely with ACTU Secretary Sally McManus on the details of the government’s wage subsidy program JobKeeper.

Commentators immediately jumped on the idea that this was a proposal for a new accord – just like the successful Prices and Incomes Accord (Accord) of the Hawke-Keating era which lasted for 13 years between 1983 and 1996. It was originally expected to last a year or two when first announced ahead of the 1983 Federal Election that swept Bob Hawke to power.

So, when looking at what Morrison is proposing in 2020, it’s important to look at what the Accord of 1983 was, and what it was not – or in the words of Crocodile Dundee: “That’s not an Accord. Now, this is an Accord!”.

First of all, it didn’t involve business or employer lobby groups. It was an Australian Labor Party (ALP)-ACTU document in response to the Coalition government of Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser and the 1982-3 recession (when Australia was experiencing double-digit inflation and unemployment and an Olympic gold medal standard of working days lost due to industrial action).

The Accord was developed by the ACTU research team of Bill Kelty, Jan Marsh and Rob Jolly when Bill Hayden was the Opposition Leader and Ralph Willis (also a former ACTU Research Officer) was the Shadow Treasurer.

When former ACTU President Bob Hawke became the Labor leader, he swept to power by promising to ‘bring Australia together’ with the Accord, as opposed to the industrial division of the Fraser years.

But the Accord in many ways was as much to the previous Labor government – the Whitlam government – as an alternative to Fraserism. The Whitlam government was hampered by poor economic management; particularly in wages policy where Prime Minister Gough Whitlam often clashed with the then ACTU President Bob Hawke.

When I interviewed Bob Hawke, he said: “what Gough knows about economics you could write on the back of a postage stamp and still have room to spare.”

But later on, Whitlam said as a retort: “Bob Hawke’s greatest advantage as Prime Minister was that he didn’t have to deal with Bob Hawke as ACTU President.”

The Whitlam government was considered by the union movement to be a lost opportunity, so when they got another chance with the election of Hawke government, they didn’t want to blow it.

As ACTU Secretary Bill Kelty once said: “As we left the unions to rally for Gough at the South Melbourne Town Hall towards the end of the 1975 election campaign, Laurie Carmichael turned to me and said ‘you know they deserved better’. And I never forgot those words until we won again in 1983.”

Second, it wasn’t just about wages and IR. It included provisions for ‘the social wage’ such as employment, Medicare, superannuation, childcare, job protection and security, taxation reform, occupational health and safety, education and training and family payments, with unions at the forefront of negotiations over social security and pensions.

Thirdly, it wasn’t a static document. It evolved as economic circumstances changed. In comparison, the original accord (Accord Mark 1) was concerned with restoring high employment and restoring the wages system after the recession.

But after severe terms of trade collapse in 1985, the second accord (Accord Mark 2) was brought in to discount nominal wage increases to ensure that the impact of the devaluation (the lower dollar meant higher import prices) wouldn’t feed into price inflation.

The adjustment was compensated by tax cuts and a deferred wage increase (taken as superannuation). This occurred right through the Accord process to enhance the social wage, improve superannuation, tie wages closely to productivity improvement and introduce tax reform.

Finally, it received broad support after being debated and negotiated across the union movement. Just as Bob Hawke brought Australia together, ACTU Secretary Bill Kelty brought the trade union movement together.

Bill Kelty brought together the likes of left of centre such as Laurie Carmichael, Tas Bull, Tom McDonald, Anna Booth, Wendy Caird, Jennie George (later ACTU President) and Marilyn Beaumont representing metal workers, wharfies, building workers, clothing workers in the rag trade, public servants, teachers and nurses together – and the centre right such as – Joe de Bruyn, John Maynes and Greg Sword representing shop assistants, clerks and storeman and packers.

It was all about social solidarity, where the strong helped the weak, for the good of the community. It was about unity, not identity politics.

The Accord also won over converts over time. None other than Paul Keating. Originally carrying suspicion of the efficacy of incomes policies from the Treasury he inherited as Treasurer, he developed a strong working relationship with Bill Kelty that continued onto the Prime Ministership. In fact, he ended up describing himself as an ‘Accord Warrior’ and was presented with a t-shirt emblazoned with “I’m an Accord Warrior” on the front by Anna Booth.

I am sure he wouldn’t even try. Firstly, Scott Morrison spoke very respectfully of Bob Hawke at the latter’s funeral noting his strong economic legacy. Secondly, it’s a different time and he has the dual challenge of managing both a public health and an economic crisis.

As his economic and public health advisors advocated, Scott Morrison decided to “go big, act early and keep the lights on” and so far it has worked reasonably well as Australia was able to ‘flatten the curve’ and minimise infections and deaths, compared to other economies beyond our shores.

The Job Keeper program has been an essential way to keep the lights on by keeping workers attached to their employers even if they are temporarily stood down.

Of course, it can. In fact, at one stage in 1982, Bill Kelty said Malcolm Fraser was talking with the ACTU about a possible deal on wages but the then Treasurer John Howard wouldn’t have a bar of it.

In the end, the Fraser Government imposed a six-month wage freeze of its own, the recession got worse and when Fraser lost the early election, he called Bob Hawke.

If Scott Morrison’s party room is uncomfortable with him talking to the ACTU, he should remind them that Australia’s longest-serving Prime Minister and Liberal Party founder Robert Menzies used to say to his MPs: “to those of you who don’t like me talking to trade unionists, remember half of them voted for us.”That’s a good message to remember in this time of Coronanomics.

Tim Harcourt is the JW Nevile Fellow in Economics at UNSW Business School and hosts The Airport Economist and The Airport Economist Podcast.