Turn off the porch light: 6 easy ways to stop light pollution from harming our wildlife

We have transformed the night-time environment in a very short time, relative to evolutionary timescales. Most wildlife hasn't had time to adjust.

We have transformed the night-time environment in a very short time, relative to evolutionary timescales. Most wildlife hasn't had time to adjust.

As winter approaches, marine turtle nesting in the far north of Australia will peak. When these baby turtles hatch at night, they crawl from the sand to the sea, using the relative brightness of the horizon and the natural slope of the beach as their guide.

But when artificial lights outshine the moon and the sea, these hatchlings become disorientated. This leaves them vulnerable to predators, exhaustion and even traffic if they head in the wrong direction.

Read more: Getting smarter about city lights is good for us and nature too

Baby turtles are one small part of the larger, often overlooked, story of how light pollution harms wildlife across the land and underwater.

Today, more than 80% of people – and 99% of North American and European human populations – live under light-polluted skies. We have transformed the night-time environment over substantial portions of the Earth’s surface in a very short time, relative to evolutionary timescales. Most wildlife hasn’t had time to adjust.

In January, Australia released the National Light Pollution Guidelines for Wildlife. These guidelines provide a framework for assessing and managing the impacts of artificial light.

The guidelines also identify practical solutions that can be used globally to manage light pollution, both by managers and practitioners, and by anyone in control of a light switch.

Read more: Bright city lights are keeping ocean predators awake and hungry

The guidelines outline six easy steps anyone can follow to minimise light pollution without compromising our own safety.

Although light pollution is a global problem and true darkness is hard to come by, we can all do our part to reduce its impacts on wildlife by changing how we use and think about light at night.

Light pollution can interfere with clownfish reproductive cycle. Shutterstock

Natural darkness should be the default at night. Artificial light should only be used if it’s needed for a specific purpose, and it should only be turned on for the necessary period of time.

This means it’s okay to have your veranda light on to help you find your keys, but the light doesn’t need to stay on all night.

Similarly, indoor lighting can also contribute to light pollution, so turning lights off in empty office buildings at night, or in your home before you go to sleep, is also important.

Advances in smart control technology make it easy to manage how much light you use, and adaptive controls make meeting the goals of Step 1 more feasible.

Investing in smart controls and LED technology means you can remotely manage your lights, set timers or dimmers, activate motion sensor lighting, and even control the colour of the light emitted.

These smart controls should be used to activate artificial light at night only when needed, and to minimise light when not needed.

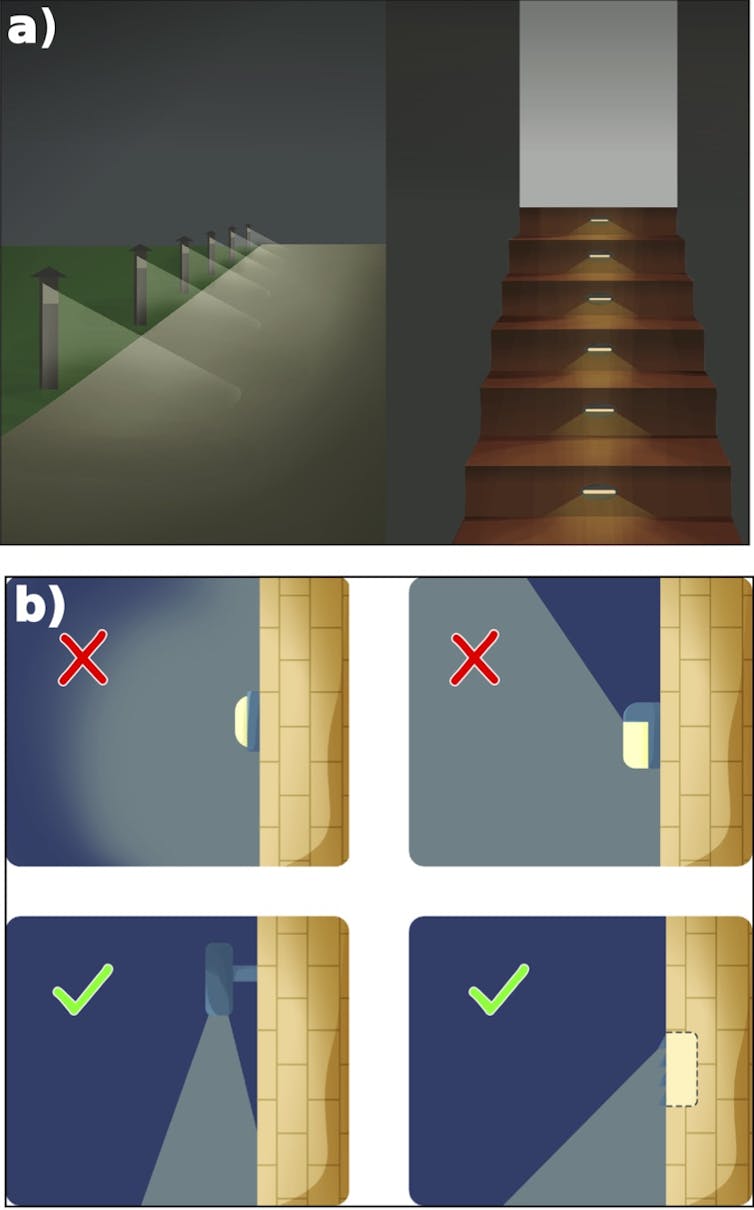

Any light that spills outside the specific area intended to be lit is unnecessary light.

Light spilling upward contributes directly to artificial sky glow – the glow you see over urban areas from cumulative sources of light. Both sky glow and light spilling into adjacent areas on the ground can disrupt wildlife.

Installing light shields allow you to direct the light downward, which significantly reduces sky glow, and to direct the light towards the specific target area. Light shields are recommended for any outdoor lighting installations.

Step 3: Keep lights close to ground (a) and use shields to light only the intended area (b) National Light Pollution Guidelines for Wildlife Including Marine Turtles, Seabirds and Migratory Shorebirds, Commonwealth of Australia 2020

When deciding how much light you need, consider the intensity of the light produced (lumens), rather than the energy required to make it (watts).

LEDs, for example, are often considered an “environmentally friendly” option because they’re relatively energy efficient. But because of their energy efficiency, LEDs produce between two and five times as much light as incandescent bulbs for the same amount of energy consumption.

Read more: Darkness is disappearing and that's bad news for astronomy

So, while LED lights save energy, the increased intensity of the light can lead to greater impacts on wildlife, if not managed properly.

Sky glow has been shown to mask lunar light rhythms of wildlife, interfering with the celestial navigation and migration of birds and insects.

Highly polished, shiny, or light-coloured surfaces – such as structures painted white, or polished marble – are good at reflecting light and so contribute more to sky glow than darker, non-reflective surfaces.

Choosing darker coloured paint or materials for outdoor features will help reduce your contribution to light pollution.

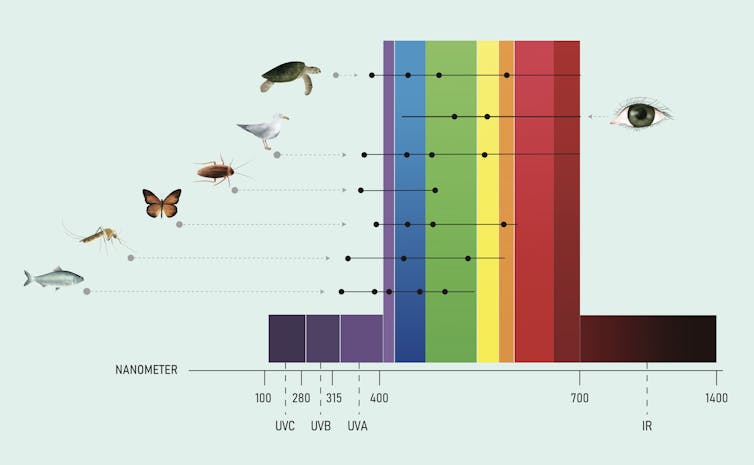

Wavelength perception in wildlife - most animals are sensitive to short-wavelength (blue/violet) light. National Light Pollution Guidelines for Wildlife Including Marine Turtles, Seabirds and Migratory Shorebirds, Commonwealth of Australia 2020

Most animals are sensitive to short-wavelength light, which creates blue and violet colours. These short wavelengths are known to suppress melatonin production, which is known to disrupt sleep and interfere with circadian rhythms of many animals, including humans.

Choosing lighting options with little or no short wavelength (400-500 nanometres) violet or blue light will help to avoid unintended harmful effects on wildlife.

For example, compact fluorescent and LED lights have a high amount of short wavelength light, compared low or high-pressure sodium, metal halide, and halogen light sources.

Read more: Sparkling dolphins swim off our coast, but humans are threatening these natural light shows

Emily Fobert, Research Associate, Flinders University; Katherine Dafforn, Senior Lecturer in Environmental Sciences, Macquarie University, and Mariana Mayer-Pinto, Senior Research Associate in marine ecology, UNSW

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.