Best place on Earth to see stars is at remote site in Antarctica, study shows

Stars viewed from a place called Dome A in Antarctica can finally be seen without their twinkle – which means in much greater detail.

Stars viewed from a place called Dome A in Antarctica can finally be seen without their twinkle – which means in much greater detail.

Have you ever wondered why stars twinkle? It’s because turbulence in the Earth’s atmosphere makes light emitted from the star wobble as it completes its lightyears-long journey to the lenses in our eyes and telescopes.

But now scientists from international research institutions including UNSW Sydney have found the best place on Earth where – with the help of technology – we can view distant stars as they really appear, without the distorting twinkle.

And it happens to be situated due south of Australia’s Davis Station in Antarctica, on a plateau 4000 metres above sea-level called Dome A.

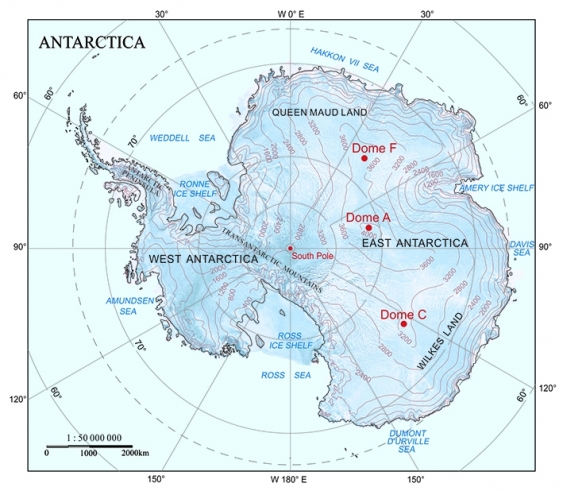

A map of Antarctica showing Dome A, which is 900km away from the South Pole. Picture: Xiaoping Pang and Shiyun Wang, Chinese Antarctic Center of Surveying and Mapping

In research published today in the journal Nature, scientists showed that the conditions at the plateau lend themselves perfectly to viewing stars from Earth with greatly reduced interference from atmospheric turbulence.

According to UNSW Science’s Professor Michael Ashley, who was part of Chinese-led research team of scientists that designed, built and set up a small telescope system at Dome A, the findings represent a fantastic opportunity to obtain better observations of the universe from ground-based telescopes.

“After a decade of indirect evidence and theoretical reasoning, we finally have direct observational proof of the extraordinarily good conditions at Dome A,” says Prof Ashley, an astronomer with UNSW’s School of Physics.

“Dome A is the highest point in the central plateau region of Antarctica, and the atmosphere is extremely stable here, much more so than anywhere else on Earth. The result is that the twinkling of the stars is greatly reduced, and the star images are much sharper and brighter.”

The KunLun Differential Image Motion Monitors atop the 8-metre high tower. Photo: Zhaohui Shang

The telescope that was installed at Dome A – the KunLun Differential Image Motion Monitor – was 25cm in aperture and placed on an eight metre platform. The height of the platform was crucial because it raised the telescope above the steep temperature gradients near the ice.

As Prof Ashley explains, turbulent eddies build up when wind moves across a changing topography such as mountains, hills and valleys.

“This causes the atmospheric turbulence which bends the starlight around so by the time it hits the ground, it's all over the place and you get these blurry images.”

But, he says, Dome A in Antarctica is a plateau that is almost dead flat for many hundreds of kilometres in every direction, making its atmosphere very stable. It's also at an altitude of more than 4000 meters – much higher than Mount Kosciuszko.

The telescopes were placed on an 8-metre tower which allowed undistorted views of stars when the atmosphere boundary layers dropped to lower than this height - about a third of the time. Photo: Zhaohui Shang

“There is this very slow wind that blows across the plateau which is so smooth that it doesn't generate much turbulence,” Prof Ashley says.

“What little turbulence there is we see restricted to a very low ‘boundary layer’ – the area between the ice and the rest of the atmosphere.

“We measured the boundary layer thickness at Dome A using a radar technique about a decade ago and it's about 14 meters, on average, but it fluctuates – it goes down to almost nothing, and it goes up to maybe 30 metres.”

The team found that by setting up their telescope on an 8-metre platform, it protruded past the boundary layer about a third of the time. Last year between April 11 and August 4 the telescope took photos every minute, and obtained 45,930 images taken when the boundary layer was lower than the 8-metre platform, it reported in Nature.

Prof Ashley says it was very challenging to finally obtain the readings and images that confirmed Dome A to be the premier location on earth to see into the depths of the cosmos.

“It was very difficult because the observations have to be made in mid-winter with no humans present. UNSW played a crucial role in designing and building the infrastructure that was used – the power supply system, computers, satellite communications – which was managed by remote control.”

But if the atmosphere plays such havoc with our instruments on Earth, wouldn’t a satellite – such as the Hubble Telescope, launched back in 1990 – be ideal for such a job?

Prof Ashley says there are a couple of good reasons why a ground telescope set up at Dome A would be the better option. Beyond the obvious savings in dollars, there are also savings in time.

“Satellites are a lot more expensive,” Prof Ashley says, “we’re talking maybe factors of 10 to 100 times the cost. But another advantage of making Earth-based observations is you can always add the latest technology to your telescope on the ground. Whereas in space, everything is delayed. And you can't easily use a lot of modern integrated circuits because they're not radiation hardened. So you end up with space lagging the technology on the ground by 10 years or more.”

Another advantage of using a telescope at Dome A rather than anywhere else on the planet is that smaller and fainter stars are suddenly much more observable thanks to the better resolution.

“Basically this means that for a given size telescope, you're going to get a lot better images at Dome A. So rather than build a big telescope on a non-Antarctic site, you could build a smaller one and get the same performance, so it's cheaper.”

The telescopes and towers were designed and built by Chinese researchers who led the study. Photo: Zhaohui Shang

There is also a strategic advantage in the location of Dome A – which is 900km from the South Pole – over other areas on Earth at more hospitable latitudes. Being so far from the equator, polar nights of 24 hours or more of darkness in mid-winter open up a much wider window to view stars.

“If you were to observe a star in say, Sydney, from when it rises to when it sets, you can only observe it for maybe eight hours a night,” Prof Ashley says.

“Whereas in wintertime at Dome A you can observe a star continuously. And for some projects like searching for planets around other stars, the fact that you can observe them continuously means you can find planets around them much more effectively.”

Looking ahead, Prof Ashley says he would like to continue the research with UNSW’s Chinese partners, and notes that China has an impressive and growing record in Antarctic scientific research. But he wonders whether Australia recognises the great potential that Dome A represents in space research.

“Dome A is a superb site for astronomical observations, and we should make every effort to participate in an international project to put a large telescope there to take advantage of the conditions.

“With Antarctica being so close to Australia, it is a tremendous opportunity,” he says.

To read paper published in Nature, click here.

Aurorae and stars from the US Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station in July 2020. Photo: Geoff Chen.