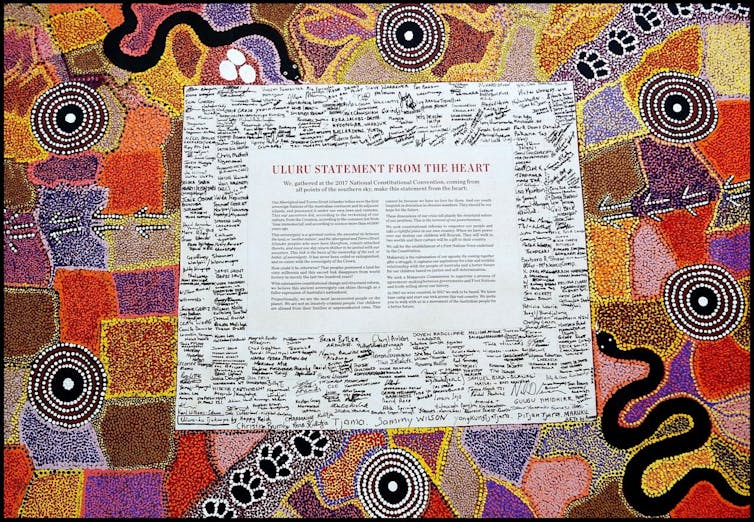

The Uluru statement is not a vague idea of 'being heard' but deliberate structural reform

The mission of Voice — Treaty — Truth in the Uluru Statement represents very carefully sequenced reforms. A proper understanding of these should guide any constitutional changes.