How to reduce offshore supply chain risks and boost onshore manufacturing

There are a number of definitive ways Australia can improve innovation and onshore manufacturing while leveraging offshore capability and reducing supply chain risks.

There are a number of definitive ways Australia can improve innovation and onshore manufacturing while leveraging offshore capability and reducing supply chain risks.

Business leaders, community groups and politicians across the politician spectrum have called for Australia to build up its domestic manufacturing capability during the Coronavirus pandemic.

With unprecedented closures of international borders and restrictions in overseas markets, Australia’s over-reliance upon global imports revealed a gap in our supply chains.

In the modern globalised world, it is difficult to disentangle the issue of trade with onshore manufacturing, says Arpita Chatterjee, a Senior Lecturer in the School of Economics at UNSW Business School.

“This is because hardly any final product we consume is manufactured in just one given location because of the prevalence of global supply chains,” says Dr Chatterjee.

Also, she says we need to remember high wage for low-skilled labor are not the only issue for manufacturing in Australia – the Australian domestic market is relatively small and far from the rest of the world. On the upside, Australia has a highly innovative scientific community, strong education sector, modern agriculture and infrastructure.

“Having this access to larger markets and cheaper labour in return for scientific innovations and more specialised high-skill intensive component manufacturing can form the basis of a gainful exchange with the world economy,” says Dr Chatterjee.

However, she believes this has been undervalued by Australia’s leaders, who have instead been reliant on the resources sector rather than encouraging entrepreneurship in the technologies of the future.

The government needs to actively engage with the scientific community and encourage entrepreneurship and build affiliate partnerships in emerging Asia, which she says will be critical to Australia’s future role in the world.

“A more integrated culture of scientific innovations and manufacturing capabilities along with trade partnerships will define our future,” says Dr Chatterjee.

Trade is not and does not have to a zero-sum game, and she explains that all partners can benefit from strategic alliances built on the principles of comparative advantage.

“Australia should focus on tying up with countries with low cost of labour in the region – South East and South Asia – such that the key innovations are developed in Australia.” She suggests the low-skilled labour-intensive parts be manufactured in these countries with the high-skilled/more sophisticated components manufactured in Australia. With the possibility of the final product assembled in some of these countries in the Indo-Pacific region, and then jointly marketed all over the world.

Dr Chatterjee says Australia has the capability to integrate into the global supply chain as the R&D and high-skill manufacturing hub in partnership with the Indo-Pacific region.

She believes a push for large-scale, low-skill manufacturing – such as textiles, apparel, footwear, for example – would not be a very realistic or ambitious goal for Australia.

“If some of these parts of the supply chain relocate from China in the future, it is likely to shift to countries like Vietnam or Bangladesh rather than to countries like Australia.”

But there are many areas where Australia can provide intellectual R&D leadership and manufacturing capability, such as healthcare products, pharmaceutical industry, agricultural innovations in water scarce environments, possibly some food-processing industries, solar technology and marine (wave) energy.

“There is no reason why Scotland can be a global leader in marine energy and Australia cannot,” Dr Chatterjee says.

It is important to focus on niche products where Australia’s scientific prowess can innovate and produce key components, which are then augmented and assembled offshore – but jointly marketed, says Dr Chatterjee.

She says a recent example of this is the Israel-India partnership which focuses on developing quick tests for COVID-19.

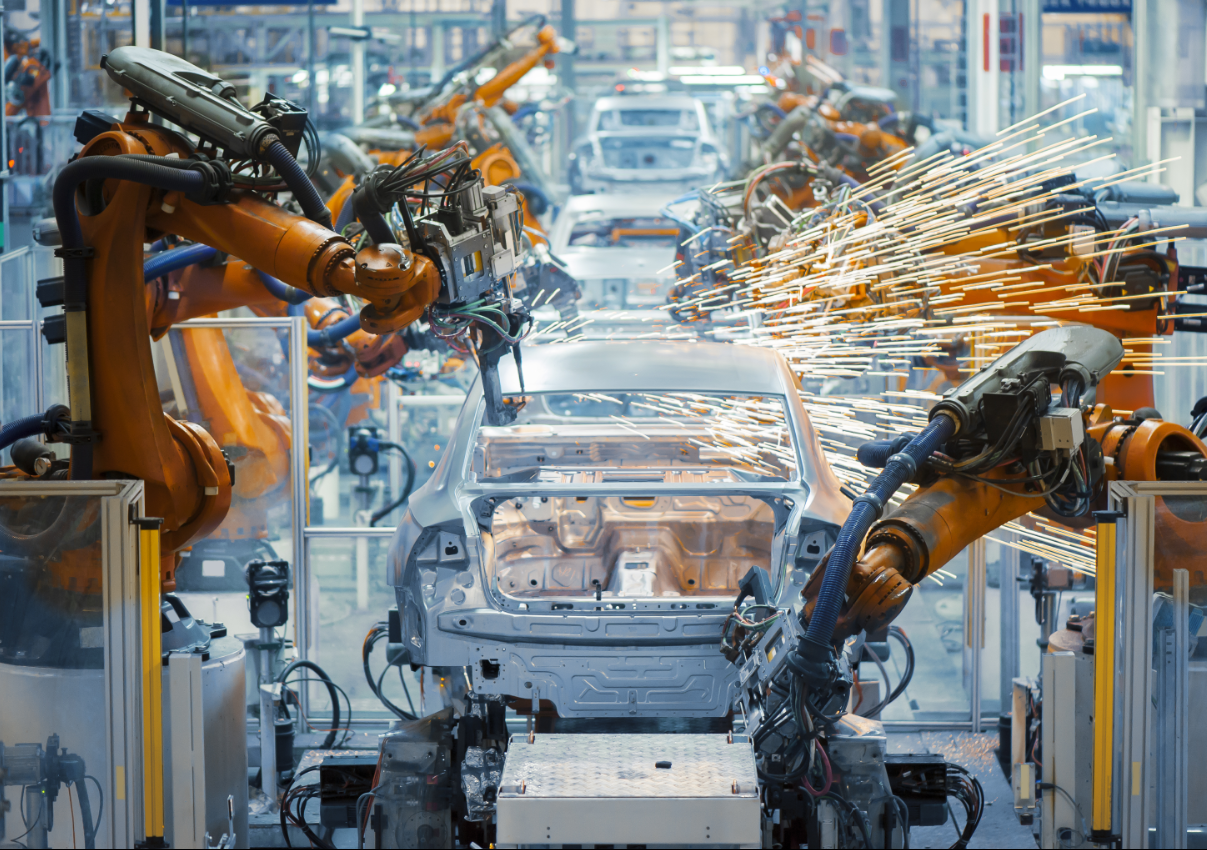

Another ambitious area for Australia could be around innovation and the manufacturing of affordable electric vehicles such as electric bikes and three-wheelers, passenger vehicles and goods transport – “in partnership with countries in emerging Asia where they are increasingly adopting an electric vehicle policy for the future”, says Dr Chatterjee.

Another area of immense potential for Australia is telemedicine and online education in emerging Asia, “given Australia’s reputation in these sectors and suitable time zone differences with the Indo-Pacific region”.

With regard to China, Dr Chatterjee says Australia needs to look beyond current trade tensions and geopolitics. China is now the world’s second largest economy with rising labour costs, and Dr Chatterjee explains it is a natural evolution for many low-cost manufacturing components to shift from China in the near future.

“But, that’s not necessarily where Australia can carve out a space for itself,” says Dr Chatterjee.

Niche products based on scientific innovation, key component manufacturing onshore, large scale manufacturing and assembly in low-cost regions of the world and joint marketing are “where I see a future,” she says.

“Australian politicians, entrepreneurs and scientists need to be in this battle together to herald a brighter future in the post-COVID global economy.”