Humans’ construction ‘footprint’ on ocean quantified for first time

The scale of people’s marine intrusion is comparable to that on land, a team of researchers has found.

The scale of people’s marine intrusion is comparable to that on land, a team of researchers has found.

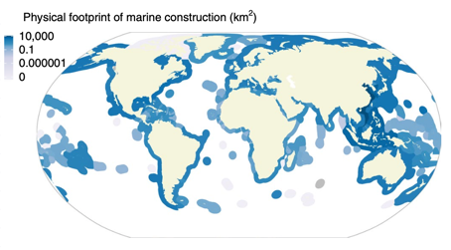

An area of approximately 30,000 square kilometres – the equivalent of 0.008 per cent of the ocean – has been modified by human construction, a study involving UNSW scientists has found.

The study – published this week in Nature Sustainability – was led by Dr Ana Bugnot from the University of Sydney and the Sydney Institute of Marine Science. Dr Bugnot undertook the research in 2018 at UNSW.

Study co-author Dr Mariana Mayer Pinto from UNSW Science said this was the first time anyone had mapped the global extent of human development in oceans.

“On land, the expansion of urban areas – which is one of the main drivers of biodiversity loss – is well quantified, but so far, we’ve had very little idea of how much the marine environment had been modified by construction,” she said.

“Such construction can cause severe environmental impacts not only directly – through the loss of habitats where construction is taking place – but also indirectly, through the associated activities with these structures, such as pollution.”

The oceanic modification includes areas affected by tunnels and bridges; infrastructure for energy extraction (for example, oil and gas rigs, wind farms); shipping (ports and marinas); aquaculture infrastructure; and artificial reefs.

Dr Mayer Pinto said the compilation of these data was a huge effort led by Dr Bugnot, achieved by gathering data on each type of construction from all over the world.

“We estimated that the physical footprint of built structures was at least 32,000 km2 worldwide as of 2018, and is expected to cover 39,400 km2 by 2028,” she said.

The extent of ocean modified by human construction is comparable to the extent of urbanised land – relatively speaking – and it is greater than the global area of some natural marine habitats, such as mangrove forests and seagrass beds.

When taking into the account flow-on effects to surrounding areas – for example, changes in water flow and pollution – the footprint is even bigger: two million square kilometres, or over 0.5 percent of the ocean.

“We showed that coastal habitats – which are among the most productive habitats in the ocean – are most affected by marine construction,” Dr Mayer Pinto says.

“But despite the negative impact, it is important to consider trade-offs between multiple objectives when considering marine construction – our earlier research put forward a framework for guiding the building and management of coastal infrastructure.

“For example, potential impacts caused by renewable energy infrastructure are preferable to those caused by traditional energy extraction, such as burning fossil fuels, and should be supported. In these cases, we need to implement evidence-based management to minimise potential negative side effects on the marine environment, such as eco-engineering approaches and/or strict policies on where to build these structures.”

Coastal habitats are most affected by marine construction. Image: Bugnot et al., ‘Current and projected global extent of marine built structures’, Nature Sustainability.

Dr Bugnot said that ocean development was nothing new, but that it had rapidly changed in recent times. “It has been ongoing since before 2000 BC,” she said. “Then, it supported maritime traffic through the construction of commercial ports and protected low-lying coasts with the creation of structures similar to breakwaters.

“Since the mid-20th century, however, ocean development has ramped up, and produced both positive and negative results.

“For example, while artificial reefs have been used as ‘sacrificial habitat’ to drive tourism and deter fishing, this infrastructure can also impact sensitive natural habitats like seagrasses, mudflats and saltmarshes, consequently affecting water quality.”

Dr Bugnot also projected the rate of future ocean footprint expansion, fuelled by people’s increasing need for defences against coastal erosion and inundation due to sea level rise and climate change, as well as transportation, energy extraction, and recreation needs.

“The numbers are alarming,” Dr Bugnot said. “For example, infrastructure for power and aquaculture, including cables and tunnels, is projected to increase by 50 to 70 per cent by 2028.

“Yet this is an underestimate: there is a dearth of information on ocean development, due to poor regulation of this in many parts of the world.

“There is an urgent need for improved management of marine environments. We hope our study spurs national and international initiatives, such as the EU Marine Strategy Framework Directive, to greater action.”

Co-author Professor Emma Johnston, UNSW Dean of Science, said she hoped the study would boost global efforts for integrated marine spatial planning, and drive improved data collection.

“Our datasets offer a starting point for a living database that can be updated over time. It will help us create improved estimates of the current physical footprint of marine construction and extent of seascape modified around these structures, and provide important tracking for future developments.

“We hope it’ll also inform more comprehensive policies that consider the big picture of marine habitat loss – this is particularly important given the lack of incentives to drive ecologically sustainable development on or below the waterline."