This video shows just how easily COVID-19 could spread when people sing together

A new study raises questions about the risks of infection for people singing in groups, especially in poorly ventilated rooms.

A new study raises questions about the risks of infection for people singing in groups, especially in poorly ventilated rooms.

Production of the reality TV show The Masked Singer was shut down after several crew members became infected with COVID-19.

It's one of several examples of COVID-19 transmission associated with singing around the world since March, prompting some jurisdictions to ban group singing altogether.

In New South Wales, for example, choral singing is banned and there are no-singing rules at weddings and nightclubs.

Now our new study, which included filming droplets and aerosols emitted when someone sings, shows how singing might be an infection risk. This is especially if multiple people sing together, in a poorly ventilated room.

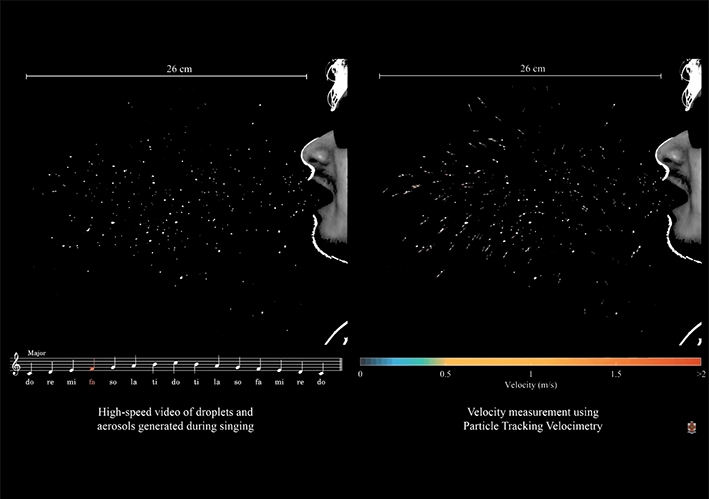

We took high-speed video of a person singing a major scale, as do-re-mi-fa-so-la-ti-do (seen below, without audio). We then tracked the emissions of droplets and aerosols.

We found certain notes, such as "do" and "fa", generated more aerosols than others. We also found the direction of emissions changed with different consonants.

One of the assumptions in infection control guidelines is that respiratory droplets settle rapidly within one to two metres of the person emitting them.

However, our results reveal most droplets we observed appeared not to settle rapidly, and tended to follow the ambient airflow.

Therefore, without adequate ventilation, these droplets may persist in aerosol clouds.

These observations may partially explain the higher infection rates of COVID-19 during group singing, even when people singing appear well.

Our findings are based on one person singing. While there may be variability in aerosol generation between individuals, it applies to singing in any groups such as churches, schools and social gatherings, all of which are vulnerable to outbreaks of COVID-19.

We've known since March of the potential for group singing to transmit SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. In this well-documented US example, 87% of 61 people who attended one 2.5 hour choir practice became infected, with two deaths. No singer had symptoms or was visibly ill during rehearsal.

Now our research adds to the growing body of research looking at the transmission risk of singing and the role aerosols might play.

We know social distancing is effective in reducing the risk of spread during normal social interactions. However, singing in a group and in closed, poorly ventilated environments may generate more aerosols than speaking.

When we sing, we vocalise louder and often hold notes for longer. This, together with multiple singers in close proximity in confined spaces for an hour or more, create conditions that may increase the spread of SARS-CoV-2.

We tend to think of only coughs or sneezes as the primary source of generating aerosols. But even breathing generates aerosols, albeit at lower concentrations.

In fact, we breathe and speak much more than we cough or sneeze. So the cumulative aerosol exposure for a group of people in a closed environment who are singing and talking, without any coughing or sneezing, may be higher than from a single cough.

We've seen online choirs as a safe alternative to traditional ones.

Other options for safer group singing now and in the future include:

Some people recommend wearing face shields while group singing. But these allow you to breathe in aerosols through the gap underneath, which may be even more likely with the powerful inhalations during singing.

No one measure alone will be enough to mitigate the risk. We need multiple measures used together — physical distancing, shorter performances, open windows, outdoor venues, softer singing and risk-based screening — to allow safer group singing.

Raina MacIntyre, Professor, UNSW; Abrar Ahmad Chughtai, Doctor, UNSW; Charitha de Silva, Lecturer, UNSW; Con Doolan, Professor, UNSW; Prateek Bahl, PhD Candidate in Engineering, UNSW; Shovon Bhattacharjee, PhD Candidate in Biosecurity, UNSW.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.