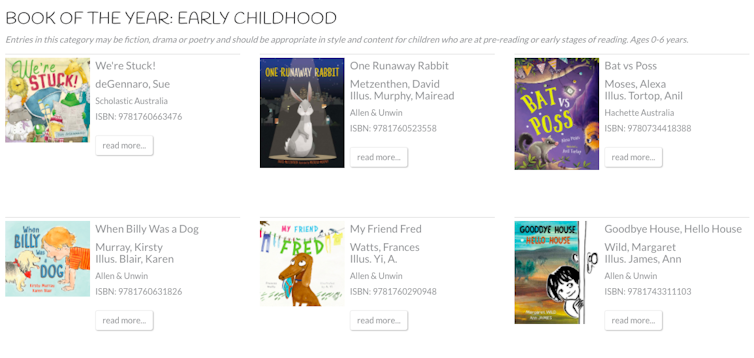

In 20 years of award-winning picture books, non-white people made up just 12% of main characters

A study shows there is a lack of ethnic and other diversity in award-winning early childhood picture books. This means our children are still getting a narrow window of the world.