Australia must vaccinate 200,000 adults a day to meet October target: new modelling

This is the key number that will determine when we can stop living under the shadow of COVID

This is the key number that will determine when we can stop living under the shadow of COVID

If R nought was the number on your lips last year, then the statistic du jour this year will be the daily number of vaccinations administered.

This is the key number that will determine when we can stop living under the shadow of COVID, the ongoing sporadic seeding events from hotel quarantine, and the necessary but disruptive lockdowns that inevitably follow.

The federal government’s COVID vaccine rollout is due to start in late February with a target of vaccinating all Australian adults by October. Vaccinating some 20 million adult Australians with two doses each in around eight months is an immense logistical challenge.

Based on our preliminary analysis, uploaded today as a preprint manuscript and still awaiting peer review, it will require the health system to rapidly get up to speed to deliver around 200,000 jabs a day, and to maintain this rate for several months.

200,000 vaccinations a day is a truly furious pace. It’s possible, but will require dedicated large-scale vaccination sites capable of delivering thousands of doses a week in addition to the enthusiastic participation of general practices and community pharmacies countrywide.

The opening act of the government’s rollout strategy will be to vaccinate the highest priority groups, including border workers, front line health-care staff, and aged-care staff and residents with the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine. Because the Pfizer vaccine needs to be stored at below -70℃, this phase will be delivered through hospital hubs with the necessary ultra-cold-chain storage facilities.

Pending approval from the Therapeutic Goods Administration, it seems likely most Australians will be vaccinated with the University of Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine. This vaccine can be stored in a regular fridge, meaning it can be distributed through general practices and community pharmacies.

Read more: The Oxford vaccine has unique advantages, as does Pfizer's. Using both is Australia's best strategy

Prime Minister Scott Morrison has suggested the rollout capacity will start at around 80,000 doses per week and increase from there. That’s 16,000 a day (over five-day weeks), well short of the required 200,000 a day. The planned peak capacity hasn’t been announced, but even back-of-the-beer-mat calculation would suggest a minimum of 167,000 vaccines per day to give two doses each to 20 million Australians in the eight months between March and October 2021. The longer it takes to reach such capacity, the higher that daily number will get — or we will not reach the target vaccination percentage this year.

There are huge benefits to getting the job done quickly as statistical modelling suggests even 50,000 doses a day in NSW will result in a longer and larger epidemic than 120,000 or more doses a day.

We ran a series of projections to estimate how long it would take to vaccinate the Australian population.

Our estimates used varied assumptions about the rate of vaccinations, the timing of the second dose, and the proportion of the population that would refuse to take a vaccine.

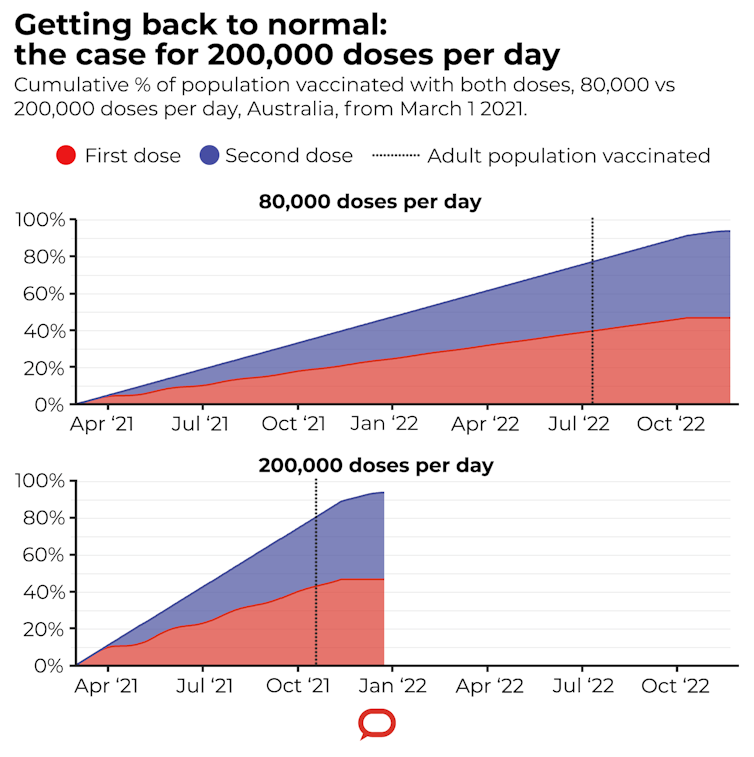

Author provided modelling/The Conversation, CC BY-ND

Our analysis finds 200,000 daily vaccinations from March would comfortably meet the October 2021 deadline. On the other hand, a rate of 80,000 per day — still seven times the PM’s starting point — would see the rollout drag on until mid-2022.

As a useful point of comparison, we can look at countries where the vaccination rollout is already underway. To make it easier to compare across countries, we can standardise by population size. On this scale, our 200,000 vaccinations per day translates to around 7,700 doses per million population per day.

This rate exceeds the best efforts of the majority of countries to date, including the United Kingdom and the United States, where the rate of vaccine administration has peaked at around 5,800 and 4,000 daily doses per million population respectively.

The outlier is Israel, where between 7,000 and 20,000 vaccinations per million population have been delivered daily throughout January, and one third of its population is now vaccinated. Several factors may have contributed to this success, including a young, largely urbanised population and a strong public health infrastructure.

Perhaps most important has been robust logistical planning, including coordination of delivery, ultra-cold-chain storage and staffing.

Returning to Australia, applications to recruit 1,000 GPs and an as-yet-unknown number of community pharmacies to join the vaccination rollout effort are currently underway.

Even if half of the 5,800 pharmacies across Australia joined with the targeted 1,000 GPs, each location would still need to administer an average of 50 doses per day, seven days a week, for about six months. Taking into account the necessary screening and record-keeping involved in addition to their usual workload, this may be quite a stretch for all but the largest practices and pharmacies.

It seems clear that to deliver at the scale needed to meet government targets won’t be possible through GPs and pharmacies alone. What’s needed are mass vaccination sites as proposed in the 2018 NSW Health Influenza Pandemic Plan. In a dedicated centre, trained nurses could vaccinate at a rate of between 80-100 people per hour. A similar approach in the UK has seen conference centres, sports stadiums, churches and mosques all co-opted as mass vaccination hubs, to great effect.

A complementary approach would be to set up drive-through vaccine clinics similar to the model of drive-through testing sites.

In the interest of openness and reproducibility, the program code base for our analysis is freely available here under an open source license.

Mark Hanly, Research Fellow, UNSW; C Raina MacIntyre, Professor of Global Biosecurity, NHMRC Principal Research Fellow, Head, Biosecurity Program, Kirby Institute, UNSW; Louisa Jorm, Director, Centre for Big Data Research in Health, UNSW; Oisin Fitzgerald, PhD Candidate, UNSW, and Timothy Churches, Senior Research Fellow, Health Data Science, UNSW

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.