Taking care of business: the private sector is waking up to nature's value

There's a growing push among businesses, including the finance sector, to protect the climate and nature.

There's a growing push among businesses, including the finance sector, to protect the climate and nature.

For many businesses, climate change is an existential threat. Extreme weather can disrupt operations and supply chains, spelling disaster for both small vendors and global corporations. It also leaves investment firms dangerously exposed.

Businesses increasingly recognise climate change as a significant financial risk. Awareness of nature-related financial risks, such as biodiversity loss, is still emerging.

My work examines the growth of private sector investment in biodiversity and natural capital. I believe now is a good time to consider questions such as: what are businesses doing, and not doing, about climate change and environmental destruction? And what role should government play?

Research clearly shows humanity is severely damaging Earth’s ability to support life. But there is hope, including a change in government in the United States, which has brought new momentum to tackling the world’s environmental problems.

Now’s a good time to talk about how humans are wrecking the planet. Daniel Mariuz/AAP

An expert report released last week warned Australia must cut emissions by 50% or more in the next decade if it’s to meet the Paris Agreement goals. Meeting this challenge will require everyone to do their bit.

Climate change is a major threat to Australia’s financial security, and businesses must be among those leading on emissions reduction. Unfortunately, that’s often not the case.

The finance sector, for example, contributes substantially to climate change and biodiversity loss. It does this by providing loans, insurance or investment for business activities that produce greenhouse gas emissions or otherwise harm nature.

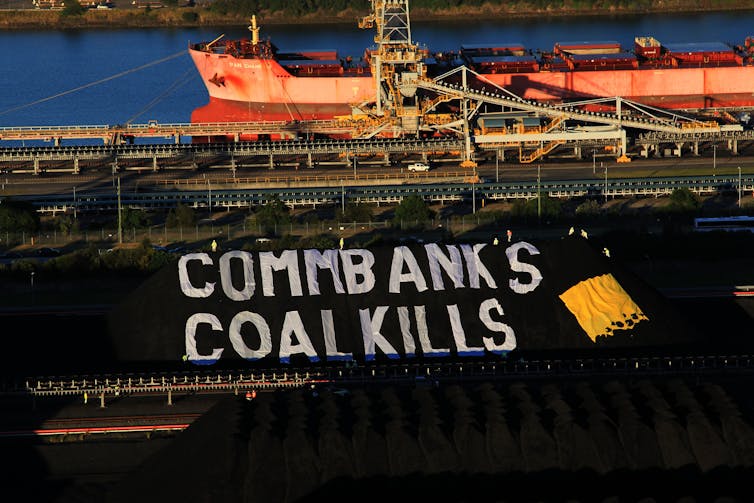

In fact, a report last year found Australia’s big four banks loaned $7 billion to 33 fossil fuel projects in the three years to 2019.

Australia’s big banks have been criticised for investing in fossil fuels. Dean Sewell/Greenpeace

Promisingly, there’s a growing push from some businesses, including in the finance sector, to protect the climate and nature.

Late last year, Australian banks and insurers published the nation’s first comprehensive climate change reporting framework. And the recently launched Climate League 2030 initiative, representing 17 of Australia’s institutional investors with $890 billion in combined assets, aims to act on deeper emissions reductions.

Read more: Worried about Earth's future? Well, the outlook is worse than even scientists can grasp

Some companies are starting to put serious money on the table. In August last year, global financial services giant HSBC and climate change advisory firm Pollination announced a joint asset management venture focused on “natural capital”. The venture aims to raise up to $1 billion for its first fund.

Globally too, investors are starting to wake up to the cost of nature loss. Last month, investors representing $3.14 trillion ($US2.4 trillion) in assets asked HSBC to set emissions reduction targets in line with the Paris Agreement. And in September last year, investor groups worth over $135 trillion ($US103 trillion) issued a global call for companies to accurately disclose climate risks in financial reporting.

HSBC’s investors are pushing for stronger climate action. Shutterstock

Climate change is not the only threat to global financial security. Nature loss – the destruction of plants, animals and ecosystems – poses another existential threat. Last year, the World Economic Forum reported more than half of the global economy relies on goods and services nature provides such as pollination, water and disease control.

Efforts by the finance sector to address the risks associated with biodiversity loss are in their infancy, but will benefit from work already done on understanding climate risk.

Of course, acknowledging and disclosing climate- and nature-related financial risks is just one step. Substantial action is also needed.

Businesses can merely “greenwash” their image – presenting to the public as environmentally responsible while acting otherwise. For example, a report showed in 2019, many major global banks that pledged action on climate change and biodiversity loss were also investing in activities harmful to biodiversity.

The global economy depends on the goods and services nature provides. Shutterstock

In the financial sector and beyond, there are risks to consider as the private sector takes a larger role in environmental action.

Investors will increasingly seek to direct capital to projects that help to reduce their exposure to climate- and nature-related risks, such ecosystem restoration and sustainable agriculture.

Many of these projects can help to restore biodiversity, sequester carbon and deliver benefits for local communities. But it’s crucial to remember that private sector investment is motivated, at least in part, by the expectation of a positive financial return.

Projects that are highly risky or slow to mature, such as restoring highly threatened species or ecosystems, might struggle to attract finance. For example, the federal government’s Threatened Species prospectus reportedly attracted little private sector interest.

That means governments and philanthropic donors still have a crucial role in the funding of research and pilot projects.

Read more: A major report excoriated Australia's environment laws. Sussan Ley's response is confused and risky

Governments must also better align policies to improve business and investor confidence. It is nonsensical that various Australian governments send competing signals about whether, say, forests should be cleared or restored. And at the federal level, biodiversity loss and climate change come under separate portfolios, despite the issues being inextricably linked.

Private-sector investment could deliver huge benefits for the environment, but these outcomes must be real and clearly demonstrated. Investors want the benefits measured and reported, but good data is often lacking.

Too-simple metrics, such as the area of land protected, don’t tell the whole story. They may not reflect harm to local and Indigenous communities, or whether the land is well managed.

Finally, as the private sector becomes more aware of nature and climate-related risks, a range of approaches to addressing this will proliferate. But efforts must be harmonised to minimise confusion and complexity in the marketplace. Governments must provide leadership to make this a smooth process.

Threatened species habitat restoration may struggle to attract private sector funding. Eric Woehler

Last week, a major report was released highlighting grave failures in Australia’s environmental laws. The government’s response suggested it is not taking the threat seriously.

Businesses and governments hold disproportionate power that can be used to either delay or accelerate transformative change.

And although many businesses wield undue influence on government decisions, it doesn’t have to be this way.

By working together and seizing the many opportunities that present, business and government can help arrest climate change and nature loss, and contribute to a safer, more liveable planet for all.

Read more: You can't talk about disaster risk reduction without talking about inequality

Megan C Evans, Lecturer and ARC DECRA Fellow, UNSW

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.