Wettest summer in five years - but is La Nina coming to an end?

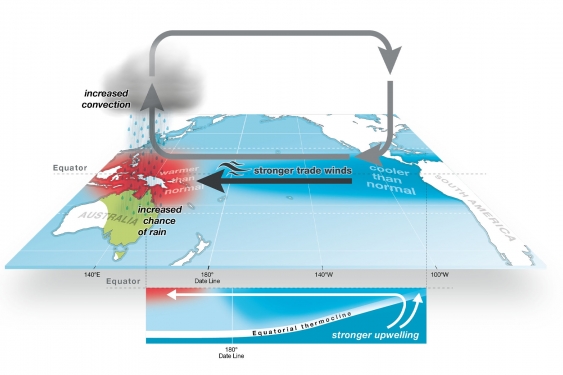

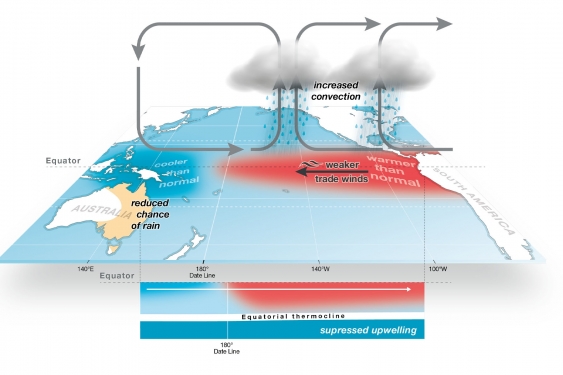

With more rain on the horizon in NSW and Queensland, a UNSW climate scientist answers our questions about whether we can expect more wet and cold from La Niña, and what’s in store for next summer.