People entering aged care with new GP experience an increase in medication

New research reveals people with dementia entering aged care with a new GP experienced a 20 per cent increase in prescribed medication.

New research reveals people with dementia entering aged care with a new GP experienced a 20 per cent increase in prescribed medication.

A new study by UNSW Sydney researchers has revealed people with dementia entering aged care and who change their general practitioner (GP) are more likely than those who retain their usual GP to experience a higher increase in medication – specifically antipsychotics, benzodiazepines and antidepressants.

The study was published today in the Medical Journal of Australia. The research analysed data from 2250 new residents with a dementia diagnosis prior to entering residential care between January 2010 and June 2014 from the Sax Institute’s 45 and Up Study in New South Wales.

“We already knew there were high levels of psychotropic medicine prescribing in residential aged care, in particular, medicines like antipsychotics and benzodiazepines,” said lead author Dr Heidi Welberry at the Centre for Big Data Research in Health, UNSW Sydney.

“There's a big uptick in prescribing just after entry to residential aged care. We also know anecdotally that many people change GP when they go into residential care. So, what we looked at was whether this increase in prescriptions was related to a change in their usual GP,” said Dr Welberry.

Prior to this research, little was known about how many residents changed their GP when they entered aged care facilities, or what effect this had on their care.

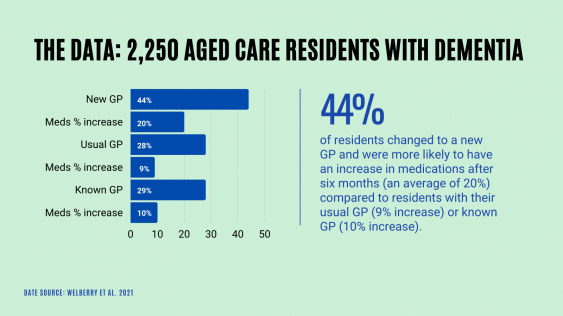

Of the 2250 new residents with dementia, just over a quarter (28 per cent) retained their usual GP, over a quarter (29 per cent) changed to another known GP (that is a GP they had seen before but not their usual GP) and nearly half (44 per cent) saw a new GP.

Residents seeing a new GP were dispensed more medicines – including antipsychotics and benzodiazepines – than residents who retained their usual or known GP. The percentage increase for medicines dispensed for residents with a new GP was 20 per cent, twice as high as those who saw their usual GP (9 per cent) or a known GP (10 per cent).

"This study has raised a lot of questions about what may drive changes in prescribing patterns,” said Dr Welberry.

Polypharmacy in older people can increase the risks of medication errors and hazardous interactions. For antipsychotics and benzodiazepines, the expected benefit for older people with dementia is small and the risk of adverse effects high.

Professor Henry Brodaty, one of the co-authors of the study said, “There's an increased risk in adverse events like stroke, and death among older people with dementia taking antipsychotics. So generally, the recommendation is to try other strategies first to help manage changed behaviours and psychological symptoms associated with dementia. This could include diversion therapy and music therapy.”

The research highlighted the pressure aged care systems are under around the world due to ageing populations and the increasing prevalence of dementia. During the Australian Royal Commission into the Quality and Safety of Aged Care, inappropriate medicine use was among the problems scrutinised, particularly the use of antipsychotics and sedatives as chemical restraints.

Professor Louisa Jorm, another co-author, acknowledged a change in prescriptions for people entering residential care may reflect events that precipitated their entry or their adjustment to their new surroundings. For people with dementia, a new environment can be distressing, and the impact can be exacerbated by having an unfamiliar GP.

The Royal Commission into Aged Care noted that pharmacologically restraining patients can arise from a “lack of knowing the person as an individual person”.

“New GPs who already see many patients in the residential care facility may possibly be influenced a bit more by the residential aged care staff as opposed to those who know their patients and families better. But this is something we don't know. This study has raised a lot of questions about what may drive changes in prescribing patterns,” said Dr Welberry.

“The Australian Medical Association (AMA) in 2018 examined barriers to GPs providing care in nursing homes. These included geographical relocation and financial barriers. As it can be difficult and inefficient for GPs to just visit a single patient in a particular nursing home, especially one they don’t regularly visit, they may transfer care to another GP.”

Dr Welberry said the main recommendation from the research was looking at new models of GP care in residential aged care – a recommendation also made by the Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety.

“The takeaway message is the importance of looking at the continuity of care for residents as they enter residential aged care,” said Dr Welberry.

Dr Welberry said she hopes this study forms part of the discussion around what a high-quality model of GP care in aged care looks like.

"We would also like to understand more about some of the drivers behind prescribing in terms of how these might differ among these different GP groups.

"For example, looking at particular aspects like how a GP may approach caring for a new patient that they haven't seen before at that entry point? I think there's certainly a lot more that we can investigate in this regard. But hopefully, it raises discussion around what good quality GP care should be in this particular setting.”

The researchers said facilitating GP continuity of care and better support for GP handover processes could potentially prevent inappropriate psychotropic prescribing for aged care residents.

“Anything that can provide a GP with greater support to spend more time in that transition period – and to really understand a new patient’s situation – will assist in establishing a higher level of care. This includes better organisation of GP care handover, including the medical history of the new patient," said Dr Welberry.

“There's a lot of pressure on GPs to care for many people, so time pressure can be really difficult.”

The study was observational, which the researchers acknowledged as a limitation – as causal inferences cannot be drawn – but the statistical techniques applied to the study strengthened the reliability of their conclusions. A major strength of the study was the large sample size and the adjustment for a wide range of socio-demographic and health factors.

Dr Welberry was supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program (RTP) scholarship and a PhD top-up through the Maintain Your Brain NHMRC Boosting Dementia Research program grant.

Contributing authors include Dr Heidi Welberry (UNSW), Professor Louisa Jorm (UNSW), Dr Andrea Schaffer (UNSW), Dr Sebastiano Barbieri (UNSW), Dr Benjumin Hsu (UNSW), Professor Mark Harris (UNSW) Professor John Hall (UNSW) and Professor Henry Brodaty AO (UNSW).

The full research paper can be viewed here.