More than banking done right, consumer data rights are set to transform our lives

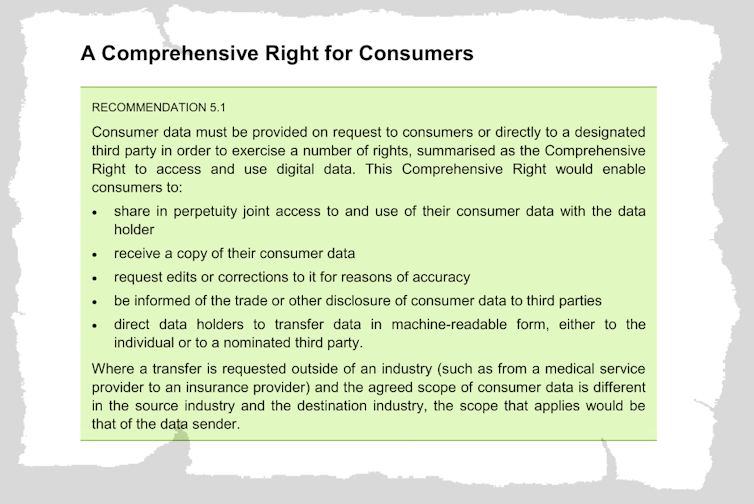

At the core of changes already underway is that the customer, not the bank, will own their banking history. It’ll make switching easier, and it’s about to spread to other services.