Angela Merkel's career shows why we need more scientists in politics

Only 7 per cent of Australia’s federal MPs have backgrounds in science. What would it look like if they were a majority?

Only 7 per cent of Australia’s federal MPs have backgrounds in science. What would it look like if they were a majority?

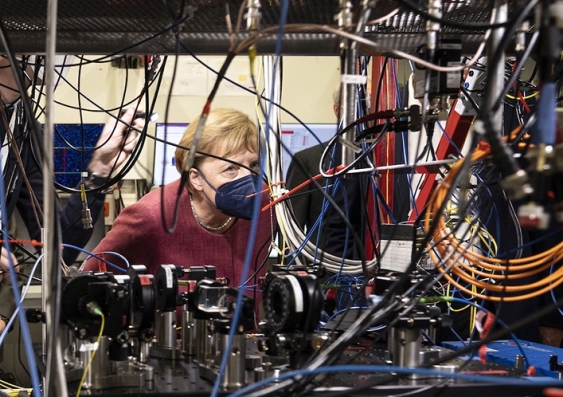

For 16 years, German chancellor Angela Merkel has guided her country through wave after wave of uncertainty, from the 2008 global financial crisis to Brexit, the imperative to drop fossil fuels, and of course the COVID pandemic. Her leadership of the European Union’s largest economy has been described as one of assurance and sure-handedness and an anchor amid stormy times, and she has been called “the de facto leader of Europe”.

Merkel has outlasted seven Australian prime ministers, and there can be no single explanation for her long stretch of success. However, her career and training as a scientist presents useful insights.

As Merkel declines a fifth term and leaves her office this month, world politics loses another scientist. In Australia we find ourselves wondering, yet again: “Across all our politics – where are the scientists?”

Globally, there have been shining examples of scientists who have entered the world of politics to great success. What are the qualities of scientists that might make them powerful and effective leaders?

Merkel retained many traits that are common among scientists throughout her long political career. She is patient and discerning. She has vision and strategy, and understands the value of planning for the long term. She is rational and empirical. And she builds collaboration and cooperation.

Finally, Merkel is known for drawing a clear boundary around what is known. She does not overstate the facts but, rather, promotes the temporary embrace of uncertainty until the data can be gathered to inform a decision.

Merkel earned her doctorate in the field of quantum chemistry a specialisation within the broad field of quantum mechanics. Widely known for the macabre “Schrödingers cat” thought experiment, quantum mechanics is guiding scientists to discover and manipulate the characteristics of atoms and sub-atomic particles.

For many, Schrödinger’s cat mystifies more than it enlightens, but the counterintuitive nature of quantum mechanics in fact reveals the strength of science. By collecting data and developing theory, by following the trail of irreconcilable observations, scientists develop and test models of the world.

And like the greatest scientific models, quantum mechanics predicts more than we can immediately explain. It is a tool that moves past our human shortcomings, of emotion-driven bias and impulse, and allows us to pry at greater truths.

Amid pandemics of viruses and misinformation, a distrust of authority and erosion of meaning, Australia has never had greater need of the tools of science and the qualities of its scientists.

Just 17 of the 227 members of Australia’s federal parliament have training in scientific, technical, medical or engineering (STEM) fields. That’s only 7 per cent.

Australia faces grave threats from many of the world’s most pressing challenges: climate change, the biodiversity crisis, pandemic variants, cybersecurity and AI challenges, and antibiotic resistance.

To meet these challenges, our national decision-makers need to objectively assess complex information, discern fact from fiction, and build collaboration and approaches that will take years, or decades, to fully come into their own.

We also need just and bold leadership with the confidence to adopt and rapidly deploy new technologies to reduce carbon emissions, build new economic sectors, and keep Australia’s digital assets safe.

Can you imagine how things might be different if there were more scientists in Australia’s federal parliament? We can.

Australia would have responded to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change “Code Red” report by introducing more ambitious carbon emissions targets, and an infrastructure investment plan to achieve them.

It would have secured Australia’s place as a world-class digital economy, growing jobs and wealth and improving equity of access to work, schools and health care for all citizens.

The government would be taking a strong, bold and evidence-informed approach to building our economy, by strengthening investment in research and development. It would provide incentives for others to do the same, generating strong GDP returns and lifting Australia from the bottom of the OECD rankings for government investment in research and development.

Australia would be rapidly building the manufacturing, energy and data infrastructure to fast-track a transition to an economy that generates no waste.

That science and politics go “hand-in-lab-glove” is no coincidence. Both seek order in a world of frightening complexity. The challenges of the 21st century – from COVID-19 to global warming – appear to be consuming us from the inside out, our national unity deteriorated by misinformation. How can a scientist make change in politics?

Angela Merkel has said her strategy was to take “many small steps” and avoid extreme reforms.

Progress can be made by invoking the rhythms of science (where decades-long projects are commonplace), by making decisions on the best available evidence, by establishing cause and consequence, and by developing and testing our models time and time again. In this way we can benefit from the steady accumulation of increasingly detailed and reliable knowledge.

In just 16 years Angela Merkel transitioned Germany from a 10 per cent renewable energy mix to the world’s first major renewable energy economy. She established a net zero emission target by 2045 while making the German economy the fourth-largest in the world by GDP. This is one of many evidence-based changes implemented by her chancellorship and one of the many features of her legacy.

Science arose through necessity, as “a candle in the dark” from the dark ages. We have enjoyed the enlightenment in which science played a major role.

And as new shadows encroach on the world, science can help keep the flame alight. Australia’s scientists: we need you.

Emma Johnston, Professor and Dean of Science, UNSW and Kylie Walker, Visiting Fellow, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.